Explore China's infamous 'ghost cities' with 65 million empty homes

Where the luxury homes stand empty and the streets are silent

It's been said that even China's population of 1.4 billion couldn't fill all the empty homes. Many are high-rise apartments in gleaming new financial districts that initially failed to take off. Others are rotten-tail homes, half-built properties in developments abandoned in the middle of construction – casualties of the nation's property crisis. Amid a turbulent economic landscape, we take a closer look at China's ghost cities and investigate whether their fortunes have changed.

Click or scroll to explore the causes, contradictions and potential solutions to these urban phenomena...

Empty shells

Writer Wade Shepard first observed the phenomenon of China's ghost cities in the early 2000s. While exploring the nation's eastern provinces, Shepard made an accidental wrong turn at the bus station in Tianti, Zhejiang. He was struck by the surreal scenes of empty high-rises and office blocks. There wasn't a soul in sight – all he could hear was his own breathing. The buildings "all appeared to be crisp and new, inside they were dark cavities, devoid of inhabitants and interior fit-out", he describes in his book Ghost Cities of China.

Rapid urbanisation

China's property boom was at its peak in the 2000s and 2010s when Shepherd visited. The strange landscape of empty, expansive parks and sprawling high-rises was often cited as proof that China’s property bubble was a fraudulent ploy to boost its GDP.

When Shepard spoke with the people building, buying and moving into these cities, he saw a different angle. His account explores China’s economic rationale behind its rapid urbanisation in the first decade of the 21st century.

Sponsored Content

What is a ghost city?

The conventional definition of a ghost city is one that was once economically booming with a large population but is no longer thriving.

China's are the opposite: many of its third- and fourth-tier cities are built up with the promise of becoming economic hubs, but due to high investment costs or a lack of economic opportunities, they fail to attract inhabitants. China’s National Committee for Terms in Sciences and Technologies better defines them as "a place that lacks an economic base, a large population and whose houses are mostly dark at night".

In more recent years, China has seen a surge in a different kind of ghost city too – partially built communities left behind by struggling developers.

The scale of the problem

The scale of the problem today is significant. At the end of 2023, Goldman Sachs estimated that China's saleable housing inventory stood at ¥13.5 trillion ($1.9tn/£1.5tn). This empty housing stock is a crucial factor that contributed to the start of the country's property crisis in 2021. Experts have speculated that China may have between 65 and 80 million empty homes.

"How many vacant homes are there now? Each expert gives a very different number, with the most extreme believing the current number of vacant homes are enough for three billion people..." said He Keng, the former deputy head of China's National Bureau of Statistics. "That estimate might be a bit much, but 1.4 billion people probably can't fill them."

The irony of China’s ghost cities

Despite this, homeownership rates remain high – around 90% of households in China are homeowners. The issue lies more with an oversupply of property. There just aren't enough buyers to satiate the country's long construction boom, which has led to a dramatic surplus of unsold housing stock and half-built developments.

Where properties have found buyers, they're not necessarily occupied. Around 20% of urban households in China own second homes and, historically, foreign buyers have purchased units as investments, too. Investment properties account for more than one-fifth of China’s entire urban housing stock, and the issue is most severe in second- and third-tier cities.

Sponsored Content

The government crackdown

In 2020, the Chinese government took action to try to deflate China's unsustainable housing bubble by restricting the amount of money larger developers could borrow. After years of overbuilding and excessive borrowing, this triggered the beginning of the end for some of the country's largest property companies. In 2021, China was plunged into a property crisis and by late 2023, developers accounting for 40% of China's house sales had defaulted on their debts, according to finance company JPMorgan.

The fallout has resulted in scores of unfinished communities deserted in the middle of construction. Giving rise to a new generation of ghost cities, these abandoned developments are known as rotten-tail buildings or 'lanwei lou' in Chinese.

The fall of an industry giant

Many people who had already handed over large sums have been left with incomplete shells after developers ran out of money. Confidence in the property sector has unsurprisingly waned and buyers have become hesitant to invest, leading to falling property prices.

The downfall of one particular industry giant in 2021 sent the property market into a tailspin. The BBC reported that the Evergrande Real Estate Group, once one of China's largest developers, defaulted on over $300 billion (£229bn) of debt. In January 2024, the company was ordered into liquidation by a Hong Kong court.

Captured here is one of Evergrande's abandoned communities, filmed by US newspaper The Wall Street Journal at the start of 2024.

Evergrande Cultural Tourism City, Jiangsu

According to its website, Evergrande Real Estate Group owns more than 1,300 developments across 280 cities in China. The Wall Street Journal estimates that the company has left around 800,000 presold homes unfinished following its collapse, along with countless commercial projects.

One of the casualties of the developer's demise is the Evergrande Cultural Tourism City in Jiangsu province on the east coast of China. Initially slated for completion in July 2021, the abandoned project was photographed here in September 2024.

Sponsored Content

Evergrande Cultural Tourism City: a rival to Disney

Encompassing 263 acres (106ha), the city was intended to intertwine a residential community with one of the country's largest new theme parks. Now the colourful rows of fairytale-esque buildings stand eerily vacant.

Designed to rival the likes of the Disney Shanghai Resort, it was one of a number of projects the company invested in to expand its cultural tourism portfolio in 2020. In total, Evergrande reportedly had more than $40 billion (£30.6bn) earmarked for the development of new theme parks and amusement parks.

Evergrande Cultural Tourism City: a derelict dream

Pictured here is a cluster of half-built residential towers at the far side of the site, where construction was halted in 2021. The high-rises were intended to supplement the construction of the amusement park.

The project was an extension of the company's Evergrande Splendor development series, which fused housing units and hotels with conference facilities and commercial and resort amenities. Jiangsu's Cultural Tourism City was to be one of around a dozen around the country – sites in Suihua in Heilongjiang province and Guiyang, the capital of Guizhou province, also stand abandoned.

Evergrande Cultural Tourism City: reclaimed by nature

Left to languish for more than three years, the fortunes of Jiangsu's fledging resort city are looking bleak. The incomplete structures are open to the elements and unprotected – there are no fences or security guards to keep out curious passersby.

Instead of holidaymakers and home-buyers, nature has moved in. The landscaped parkland has become overgrown and the whimsical amusement buildings and barren residential towers are falling victim to the elements. In the wake of Evergrande's collapse, it's not clear what will happen to the eerie wasteland.

Sponsored Content

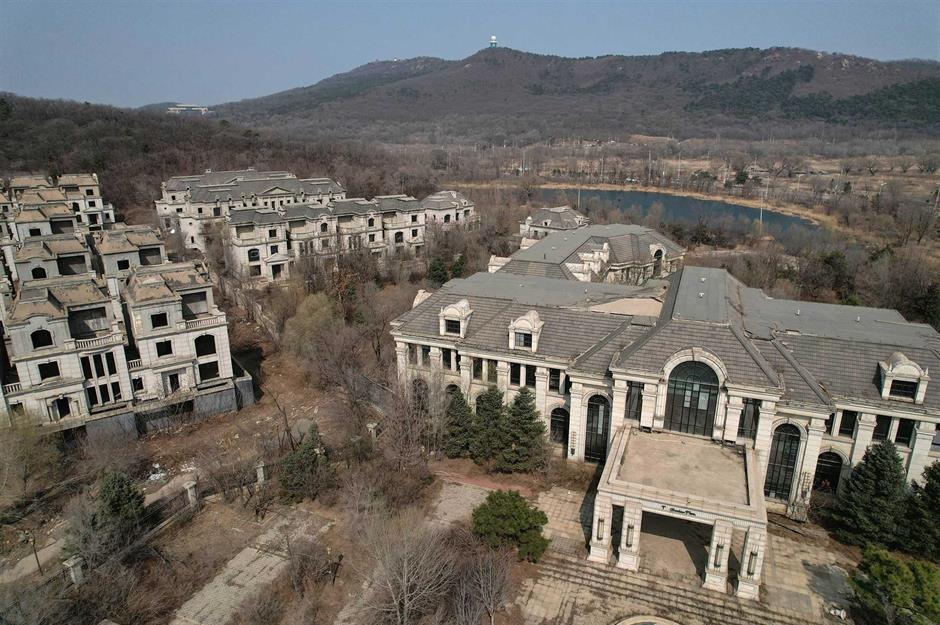

State Guest Mansions, Shenyang

Another development that fell by the wayside is the State Guest Mansions in the foothills of Shenyang in the northeast of the country. Designed to resemble a European manor house, around 260 residences and luxury amenities were planned for the site, which was intended to accommodate visitors of the provincial government.

These images, taken in March 2023, show the enormity of the compound and its rows of unfinished mansions. While construction began on the project in 2010, it ground to a halt just two years later, according to the non-profit newspaper Hong Kong Free Press.

State Guest Mansions: felled by the property crisis

Officially, the reasons behind the project's abandonment aren't clear – but a local farmer told the news organisation AFP: "Frankly, it was because of official corruption. They cut off the funding and cracked down on uncontrolled developments, so it was left half-finished."

If the pause in construction was temporary, the bursting of China's property bubble made it permanent. Developers Greenland Holdings found itself in hot water following the government crackdown on excess borrowing. The state-backed company defaulted on a $432 million (£330m) debt in 2023. To make matters worse, China's English-language news service Yicai Global reported in July 2024 that Greenland's director was under investigation by Shanghai's anti-corruption watchdog.

State Guest Mansions: faded grandeur

Inside one of the mansions, the grandeur of the project comes into focus, from the double-height ceilings to the chandeliers and marble columns.

It's clear that the community's target market was the super-rich – these homes would likely have sold for millions. This may perhaps have been another factor that influenced the project's failure. When Chinese President Xi Jinping rose to power in 2012, he criticised displays of wealth and vowed to wage war on government corruption, likely reducing the interest in outwardly lavish real estate.

Sponsored Content

State Guest Mansions: an unexpected reinvention

Despite its abandonment, the site isn't devoid of life. Local farmers have since reclaimed the ghost town as an agricultural site. Pens of cows have been sandwiched between the empty mansions and the dirt roads have been cultivated to grow produce.

While this development has had something of a reinvention, communities of rotten-tail homes are emblematic of China's floundering property sector. The Chinese government has sought to ease the real estate crisis by relaxing mortgage rules, releasing extra funding and introducing new initiatives that will see local governments purchase some empty homes for social housing. But will it be enough to revive these half-built communities?

Kangbashi or Ordos New Town, Inner Mongolia

Yet history has shown that China's ghost cities can be brought back from the brink. Once dubbed China's answer to Dubai, Ordos district Kangbashi was planned as a massive civic mall with abundant monuments, cultural institutions, colossal plazas, large commercial and residential complexes and towering government buildings.

Built in just five years, the new city was intended to house one million people – a number that planners scaled down to 300,000 as the project progressed – and attract commuters from nearby Dongsheng (Old Ordos).

Kangbashi: delayed residents

Kangbashi, or Ordos New Town, was built as a futuristic hub on top of the former desert village. While work began in 2004, swathes of the town's major facilities were only opened in 2009. High property taxes and rushed construction prevented people from moving, making its main inhabitants migrant construction workers.

Sponsored Content

Kangbashi: government tempts movers

Although the population started out at about 30,000, it has increased over the years thanks to city government measures, including curbing new building work. The local government also encouraged neighbouring residents to relocate to Kangbashi with generous compensation.

Government offices were relocated to get public officials to settle closer to work and even acclaimed high schools moved into the area. By 2017, there were more than 4,750 businesses in the district and a permanent population of 153,000.

Kangbashi: China's student housing troops

In 2021, local estate agents reported that apartment blocks were being sold out, causing local developers to build new complexes. Meanwhile, in the first half of 2022, Kangbashi's GDP measured just over ¥6.6 billion ($936m/£714m), according to the state-run English news portal China Daily.

The dramatic change is a direct result of intense competition among parents of high school students to secure places at China's top universities. For instance, Ordos No. 1 High School, which has sent students to leading universities in Beijing, calls Kangbashi home.

Kangbashi: housing market on the up

Attracted by the good schools, parents buying up in catchment districts drove up house prices. In Kangbashi, the average price per square foot for a property in 2024 is ¥1,792 ($254/£194), or ¥19,274 per square metre ($2.7k/£2.1k).

According to local government data from the end of 2023, an estimated 126,900 people live here, with tens of thousands of students enrolled in local schools.

Sponsored Content

Tianducheng or Sky City, Hangzhou

Rural farmland was re-zoned for the construction of Tianducheng, a housing development located on the outskirts of Hangzhou in Zhejiang, about an hour by bullet train from Shanghai.

With planners drawing inspiration from Paris, the luxury development comes equipped with its own Champs-Élysées and a replica fountain from the Luxembourg Gardens. The city is constructed around its pièce de résistance: a clone of the Eiffel Tower, a third of the size of the original.

Tianducheng: a success story

Occupying 12 square miles (31sqkm), Tianducheng was built to accommodate 10,000 inhabitants at launch. But early reports suggested it had drawn as few as 2,000 residents, this absence of citizens attributed to its odd location – the development is surrounded by farmland, the countryside full of dead-end roads.

Nevertheless, over the years, 'Paris II' has attracted new residents and its population had increased to around 30,000 by 2017, according to some reports.

Zhengdong New District, Zhengzhou

In 2001, Japanese architect Kisho Kurokawa was commissioned to draw up a comprehensive urban plan for Zhengdong, consisting of a core business district, living area and a college district (Longzihu). The heart of Zhengdong New District, Longzihu College Park and the fan-shaped Zhengzhou International Convention and Exhibition Center was all just barren development land when they broke ground in 2003.

Sponsored Content

Zhengdong New District: initial struggles

Zhengzhou's mayor forecast in 2006 that the new district would expand to 193 square miles (500sqkm) with a population of five million by 2020. However, it took a while for people to show up. A March 2013 60 Minutes report documented "vacant subdivisions uninhabited for miles and miles and miles".

However, things started to change soon after these reports and Zhengdong New Area has since experienced substantial growth.

Zhengdong New District: rapid growth

Thanks to the arrival of several regional bank headquarters and the building of the Zhengzhou East railway station, the mid-2010s saw Zhengdong transform from an eerie ghost city to one bustling with life.

By 2015, Wade Shepard reported that the district had about 150 financial institutions and 1.4 million people. Data from the Standard Chartered Bank showed that the occupancy rate had doubled to nearly 60% by May 2014. "Zhengdong is not a ghost city anymore," he said.

Zhengdong New District: “newer district”

Since that report, Zhengdong New District’s economy has flourished. From 1998 to 2021, the population of the metropolis has reportedly grown more than 102%, with a GDP growth rate of over 1,835%.

Zhengdong’s success story continues with the development of a new district. Zhongyuan Longzihu Smart Island was designed as a hub of entrepreneurship and innovation and integrates its infrastructure with AI algorithm services.

Sponsored Content

China’s ghost cities: a temporary condition?

So what next for these metropolises? After 25 years of development, raising districts out of desert villages, wastelands and reclaimed lands, some of them could be considered as successful.

However, China's property crisis could exacerbate the problem. As developers default on loans and declare bankruptcy, there's a risk that some of these fledgling cities could fall silent for good. Only time will tell how the economic fortunes of so many empty communities play out...

Loved this? Discover more fascinating real estate stories from around the world

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature