Inside the historic mansions of Canada's super-rich

Tour the storied estates of Canada's wealthiest people

Step back in time to the Gilded Age of Canadian industry and explore the lavish mansions built by some of the country's wealthiest tycoons. From railway robber barons to millionaire merchant bankers, these historic moguls elevated domesticity to a high art, resulting in some of the most lavish homes Canada has ever seen.

Click or scroll on to discover the secrets of these spectacular estates…

Sir Allan Napier McNab

Soldier, lawyer, businessman and politician, Sir Allan Napier McNab (19 February 1798 – 8 August 1862) wore many hats throughout his storied career. After a youth spent in military service, McNab went on to practice law and purchase and develop land.

McNab was ambitious and entrepreneurial. In addition to his lucrative property development ventures, he collaborated with Glaswegian merchant Peter Buchanan to construct the Great Western Railway.

From this success, he launched his political career and served as premier of the United Canadas from 1854 to 1856, which was a British colony at the time.

Dundurn Castle, Hamilton, Ontario

Known as Dundurn Castle, McNab’s family seat in Burlington Heights, Hamilton was a 40-room neoclassical villa designed by English architect Robert Wetherall.

The home took three years to build and was completed in 1835. The main house draws on both the Regency and Italianate styles, complemented by a collection of classical and Gothic Revival outbuildings.

Dundurn Castle: a remarkable historic home

Dundurn Castle has been deemed one of the finest surviving examples of the picturesque aesthetic style in Canada and among the country's most remarkable historic homes.

The house is pictured here in May of 1900, festively decorated for its opening day, when the home and its 32 acres (13ha) of rolling grounds overlooking Burlington Bay were finally made accessible to the public.

Dundurn Castle: state-of-the-art amenities

Inside, McNab fitted the home out with all the modern luxuries money could buy, including gas lighting, running water and even a toilet with running water – the first of its kind in Upper Canada.

The rooms were all lavishly appointed, particularly the public spaces such as the elegant sitting room, pictured here decorated for Christmas. Under McNab’s ownership, Dundurn Castle became known across the country as a glamorous party destination and the mogul enjoyed hosting on a grand scale.

Dundurn Castle: a portal to the past

After McNab’s death in 1862, the house was used as an institute for the deaf before being sold to the city of Hamilton in 1899.

Meticulously restored in the 1960s, the mansion was designated a National Historic Site of Canada and today it's open to the public as a museum. Its beautifully restored rooms, pictured here, let visitors see first-hand how Canada’s super-wealthy would have lived in the 19th century.

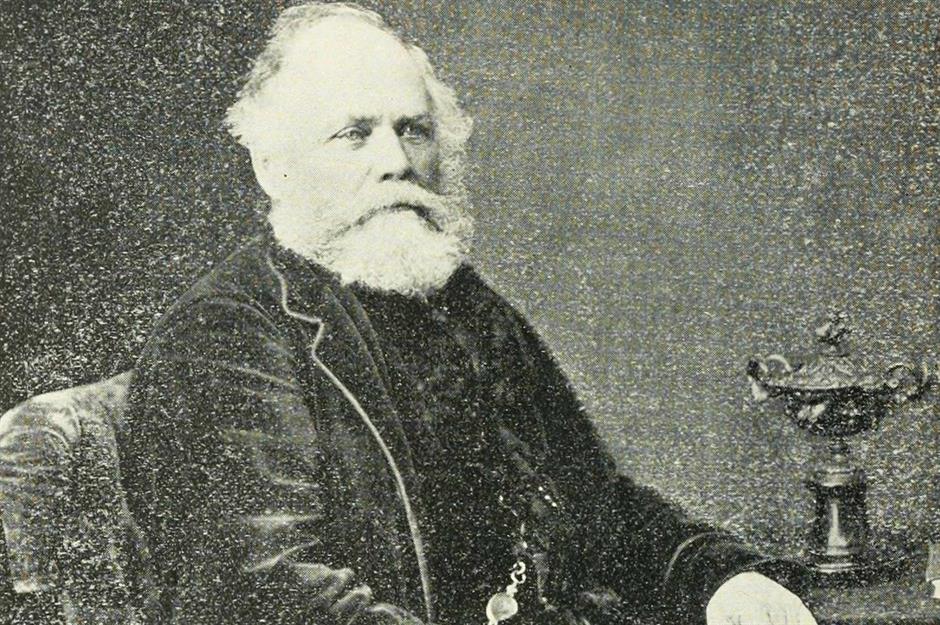

Sir Hugh Allan

Scottish-born Sir Hugh Allan (29 September 1810 – 9 December 1882) immigrated to Montreal in 1826, where he became a prominent shipping magnate, railway promoter and financier. In addition to heading the Montreal Ocean Steamship Co., Allan also dabbled in mining, manufacturing and communication, serving as the director of two American telegraph companies as well as the Montreal Telegraph Co.

In 1871, Allan was knighted by Queen Victoria for his substantial industrial contributions. At the time of his death in 1882, he was said to be the wealthiest man in Canada.

Ravenscrag, Montreal, Quebec

Allan’s grandiose residence is straight from the pages of a Victorian Gothic novel and boasts a name to match: Ravenscrag.

In 1860, Allan paid £2,250 – approximately CAD$430,000 ($311k/£233k) in today’s money – for 14 acres (6ha) on Montreal's Mount Royal. He developed 10 acres (4ha) into his private estate, building a 34-room mansion in the Italianate style for himself and his wife, Matilda Caroline Smith.

Allan hired Quebec-born architect Victor Roy to design the home’s grey-stone exterior and Liverpool-born architect John W. Hopkins to style its interiors.

Ravenscrag: inspired by Scotland

Completed in 1863, the home included a 98-foot-long (30m) conservatory, a 2,760-square-foot (256sqm) ballroom, a billiard room, a library and a distinctive 75-foot (23m) tower with spectacular views over the city to the river, the Adirondack Mountains and even the Green Mountains of Vermont.

It was this distinctive feature that inspired the house’s name after the ruined tower of ‘Ravenscraig’ in Ayrshire, Scotland, which Allan had loved as a boy.

Ravenscrag: at the centre of high society

While the home had certainly been impressive under Allan’s tenure, it was not until his son Montagu became master of the house that Ravenscrag became a hub of Montreal high society.

In 1889, Montagu commissioned Andrew Thomas Taylor to enlarge the east wing of Ravenscrag. During the 1890s, Taylor also expanded the dining room a further 10 feet (3m), enlarged the veranda, terraces and balconies and renovated the stables to accommodate Montagu’s collection of thoroughbred horses.

By the time Taylor’s expansions were complete, Ravenscrag was the second-largest home in Canada.

Ravenscrag: a new chapter begins

Ravenscrag had grown from 34 to 72 rooms, spanning a sprawling 53,475 square feet (4,968sqm) over five floors, as well as beautifully landscaped gardens with a fishing lake, grotto and several greenhouses.

However, the home didn't stay in the family. Buried by property tax and having lost all of his children to the First World War, Montagu was forced to auction off the mansion’s contents and gifted Ravenscrag to the Royal Victoria Hospital.

Today, the shell of the house is now a psychiatric facility attached to the Montreal General Hospital.

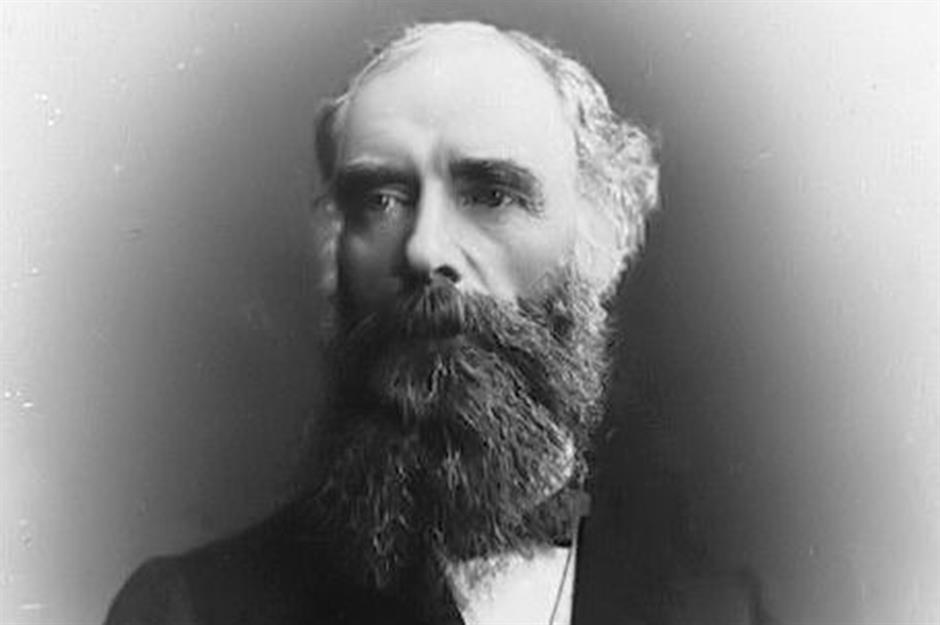

Donald Smith, 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal

Another Scottish-born titan of Canadian industry, Donald Alexander Smith (6 August 1820 – 21 January 1914), 1st Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal, was a railroad financier, diplomat and philanthropist.

The many prestigious roles he held in his lifetime included the governor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, president of the Bank of Montreal and the Canadian high commissioner to England. He also played a prominent part in the development of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Smith's more charitable interests led him to found the Royal Victoria College for women at McGill University and help finance Montreal's Royal Victoria Hospital.

Lord Strathcona House, Montreal, Quebec

Around 1880, Lord Strathcona commissioned a home from a mysteriously unknown architect to be built in the late Victorian style, featuring a blend of Scottish and French influences.

The final product was considered the most glamorous house in Montreal, featuring a rough-textured stone façade, dramatic dormer windows and a towering turret. In 1911, Strathcona hired architectural duo the Maxwell brothers to design some additions and alterations to the house, including a new conservatory in the Beaux Arts style.

Lord Strathcona House: luxurious living spaces

Located on Montreal's desirable Golden Square Mile, the house was exceedingly extravagant. Perhaps the most eye-catching feature of the home was the conservatory, a beautifully decadent extension to the otherwise austerely Victorian home.

Pictured here complete with towering palms, ornamental lampposts and plenty of plush seating, the beautiful space was the perfect spot to retreat to for a bit of afternoon sun.

Lord Strathcona House: consigned to the history books

Another of the home’s highlights was its long gallery, built to house Strathcona’s famed art collection. Decorated with damask-panelled walls and a double-height, ornately plastered ceiling, the spectacular space functioned as a hybrid between a private library and art gallery, with plenty of antiques and gilded cabinets scattered throughout.

Sadly, the mansion was demolished in 1941 and its remarkable interior consigned to the history books.

Lord Strathcona's English stately home

In addition to his Montreal home, Strathcona also had an English country estate. Knebworth House was originally built in 1490 by Sir Robert Lytton, but was enlarged and remodelled into its present-day Tudor-Gothic appearance in the 1840s.

Having received a peerage in 1897, Lord Strathcona took up residency at the property two years later in his capacity as Canadian high commissioner to England. He maintained the home as his country seat until his death in 1914.

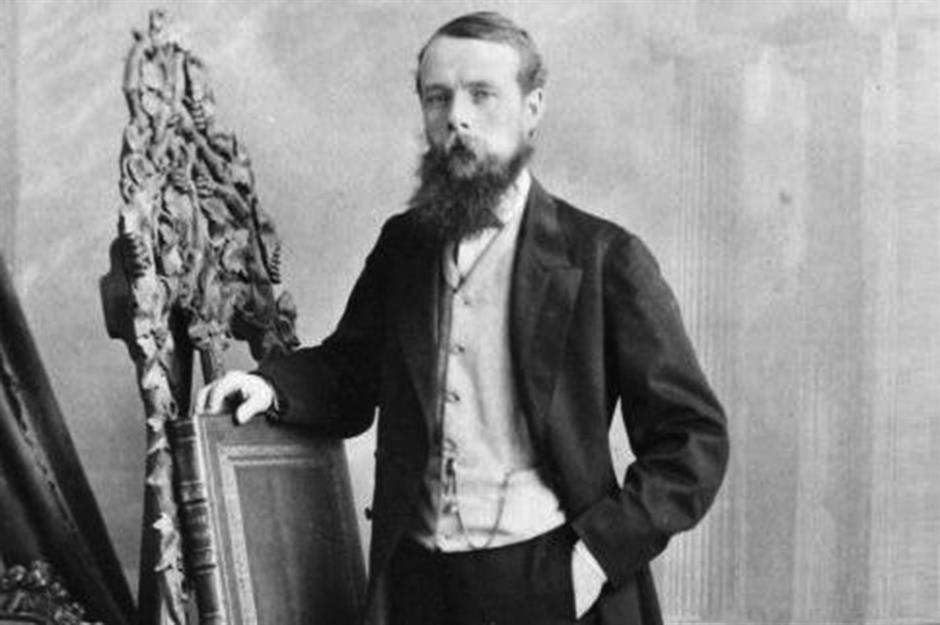

George Stephen, 1st Baron Mount Stephen

George Stephen (5 June 1829 – 29 November 1921), 1st Baron Mount Stephen, was a Scottish-born banker and railway president considered to be instrumental to the success of the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR).

Having served as first the director and later the president of the Bank of Montreal between 1873 and 1881, he turned his attention to the railway industry. After he helped to revive the struggling St. Paul, Minneapolis and Manitoba Railway, he became president of the CPR.

In 1888, Stephen moved to England, where he was made a baronet in 1886 and raised to the peerage as Baron Mount Stephen in 1891.

The George Stephen House, Montreal, Quebec

Known as the George Stephen House, Stephen’s family home on Drummond Street in Montreal, Quebec was commissioned in 1880 and designed by prominent local architect W. T. Thomas.

The home was built by Montreal contractor J. H. Hutchison and took three years to finish, with numerous craftspeople brought over from Europe to complete the lavish interiors.

A classic example of the Renaissance Revival style popular in the Victorian era, the home was considered one of the most opulent and elegant mansions in Montreal of its era.

The George Stephen House: breathtaking architecture

The home features exquisite masonry across its exterior, from carved arches around the windows to a portico supported by four ornate columns.

Meanwhile, the property's interiors were designed according to the aesthetic style, with the entertaining spaces in particular finished to a high standard. Pictured here is an old photo of the dining room, which was adorned with a coffered ceiling, intricate panelling across the walls and a magnificent fireplace surround.

The George Stephen House: dressed to impress

The living room was another lavish centrepiece in the home, featuring elaborate woodwork, carved stone fireplace mantels, stained-glass windows depicting scenes and quotations from Shakespeare, richly upholstered furnishings and a decadent collection of porcelain and silver.

Packed with paintings, tapestries, rare collections and antiquities, the home resembled a small museum in its heyday. However, given that Stephen used the home to both conduct business meetings and host grand parties for his friends, it's unsurprising that he wanted the interiors to be dressed to impress.

The George Stephen House: preserved for posterity

The mansion sits in Montreal’s famous Golden Square Mile, the most fashionable neighbourhood in the city at the time of its construction. However, after the First World War, the wealth and splendour of the area were depleted during the Great Depression.

No longer practical as a private residence, the home was repurposed after Stephen’s death in 1921 as the Mount Stephen Club, a private members’ club for businessmen. The club operated from 1926 to 2011 and the house was designated a National Historic Site in 1971.

Thomas George Shaughnessy, 1st Baron Shaughnessy

Thomas George Shaughnessy (6 October 1853 – 10 December 1923), later the 1st Baron Shaughnessy, began life as the son of Irish Catholic immigrants in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. After working a series of menial jobs, Shaughnessy moved to Montreal in 1882 at the age of 29 to work for the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR).

Ambitious and a perfectionist, Shaughnessy quickly rose through the ranks of the railway company thanks to his strict adherence to protocol. His rigour and discipline made him well-equipped to manage the chaos of the rapidly expanding railway industry. Under his eventual presidency, the CPR's miles of track almost doubled.

Shaughnessy House, Montreal, Quebec

Shaughnessy’s two great loves were widely acknowledged to be his work and his family. He was able to provide lavishly for the latter thanks to the profits of the former.

Between 1892 and 1923, the Shaughnessy family resided at Shaughnessy House in Montreal, Quebec, which had been built in 1876 for the McIntyre and Brown families. While the stately home appears to be a single residence, it is in fact two separate seven-bedroom homes.

Shaughnessy House: a residence for railway tycoons

A quintessential example of French Second Empire architecture, the house was designed by Anglo-Canadian architect William Tutin Thomas.

While the home was ultimately named after Shaughnessy, he was preceded at the residence by two other presidents of the Canadian Pacific Railway: Duncan McIntyre and Sir William Van Horne. Because of this, the home was already ‘presidentially’ appointed by the time the Shaughnessy family moved in.

It was described by Van Horne in a letter to his wife as “a very bright and cheerful place and everything about it is nearly perfect."

Shaughnessy House: elaborate interiors

No expense was spared on the home’s interiors, which feature spectacularly carved coffered ceilings, ornamental marble and parquet floors, large marble fireplaces, intricate cornicing and moulding, smoked glass saloon-style doors and elaborately carved decorative columns.

A lover of luxury, Van Horne had overseen the painting of the rooms himself prior to his family’s arrival and had imported gas light fixtures from New York – the epitome of opulence for the time.

Shaughnessy House: saved from the wrecking ball

The Shaughnessy family sold the home in 1923 just before Thomas’s death. In the decades that followed, the home passed through many hands and served many functions, including a hospital and a women’s boarding house.

In 1974, the home was rescued from demolition by architect and preservationist Phyllis Lambert, daughter of local tycoon Samuel Bronfman. Lambert oversaw the restoration of the property and had it designated a National Historic Landmark, later turning it into the Canadian Centre for Architecture.

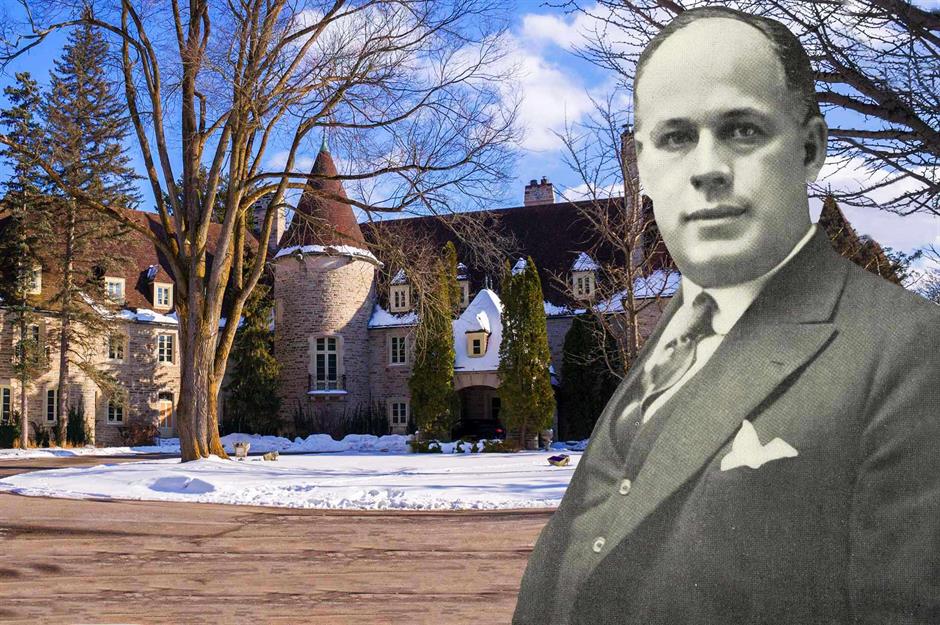

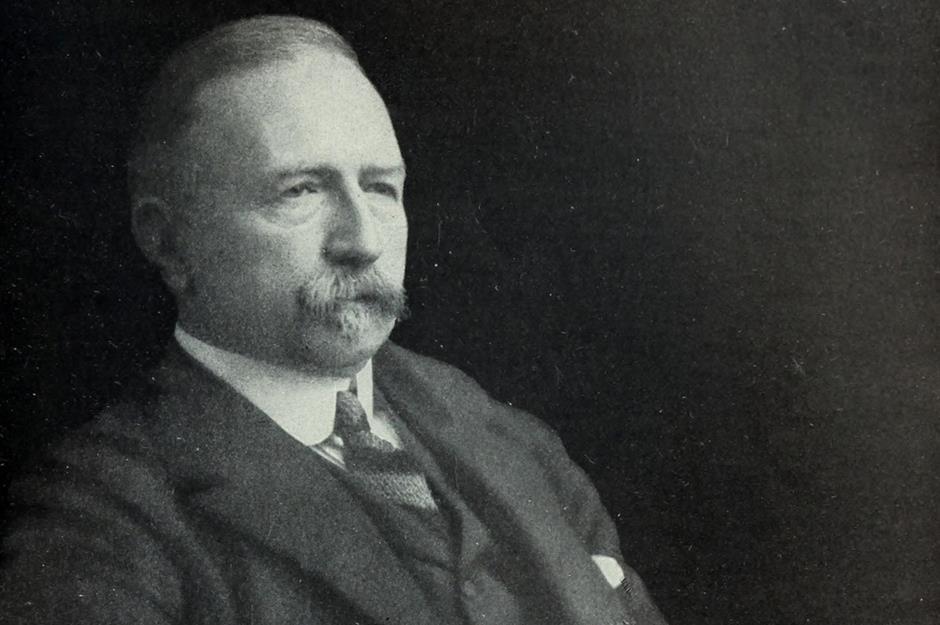

Sir John Craig Eaton

Sir John Craig Eaton (28 April 1876 – 30 March 1922) was a Canadian merchant and philanthropist who took his father’s family store, the Timothy Eaton store on Yonge Street in Toronto, and turned it into a highly lucrative company.

When Timothy died in 1907, he left an estate worth $180 million (CAD$250m/£135m) in today's money. Under Sir John, the retail business expanded across Canada during the early 1900s, opening several branches and even moving into manufacturing.

Eaton was well-regarded by his contemporaries for his efforts to improve working conditions for his employees, as well as his generous contributions to organisations including the Ontario College of Art, the Toronto General Hospital and the University of Toronto.

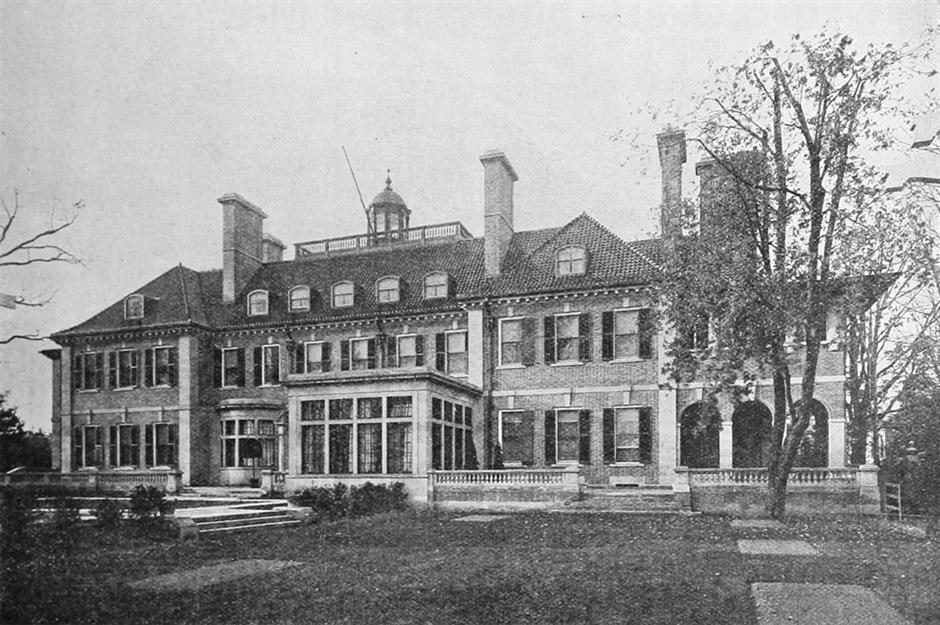

Ardwold, Toronto, Ontario

Eaton and his wife, Lady Flora, commissioned the construction of Ardwold in 1909 in the affluent neighbourhood of Davenport Hill. It was appropriately named after the Gaelic word meaning high green hill.

The home was designed by architect A. Frank Wickson in the Georgian style. It boasted 50 rooms, including a music room, a billiards room, 14 bathrooms and even an elevator. Built to impress, Ardwold's double-height great hall featured a pipe organ, which Eaton would often play for his guests.

Ardwold: secret tunnels and nursery suites

In addition to the more conventional formal spaces, the home also featured the more opulent addition of a five-room nursery suite to accommodate Eaton’s six children, complete with its own kitchen and hospital wing.

There was also said to be a curious underground tunnel connecting the main house with a glass conservatory and an indoor swimming pool.

Ardwold: a lost estate

Ardwold was nestled in 11 acres (4.5ha) of beautifully manicured grounds, including Italian-inspired gardens and fountains, which made an ideal backdrop for social gatherings and costume parties like the one pictured here.

Considered one of the most impressive properties in Canada in its day, the home had spectacular views out over Toronto from its elevated location.

Sadly, the property was sold in 1922 after Eaton died of pneumonia at the age of just 45. In 1936, the mansion was completely demolished.

The Eatons' surviving mansion

However, another Eaton family estate, Eaton Hall, still stands today on a 700-acre (283ha) parcel of land that Sir John and Lady Flora acquired in 1920. While Eaton never saw their plans come to fruition, Lady Eaton forged resolutely ahead, constructing a spectacular 36,000-square-foot (3,344sqm) Norman-style mansion.

When Lady Eaton passed away in 1970, the property changed hands and was repurposed as a hospitality and events venue, as well as an education space for Seneca College students.

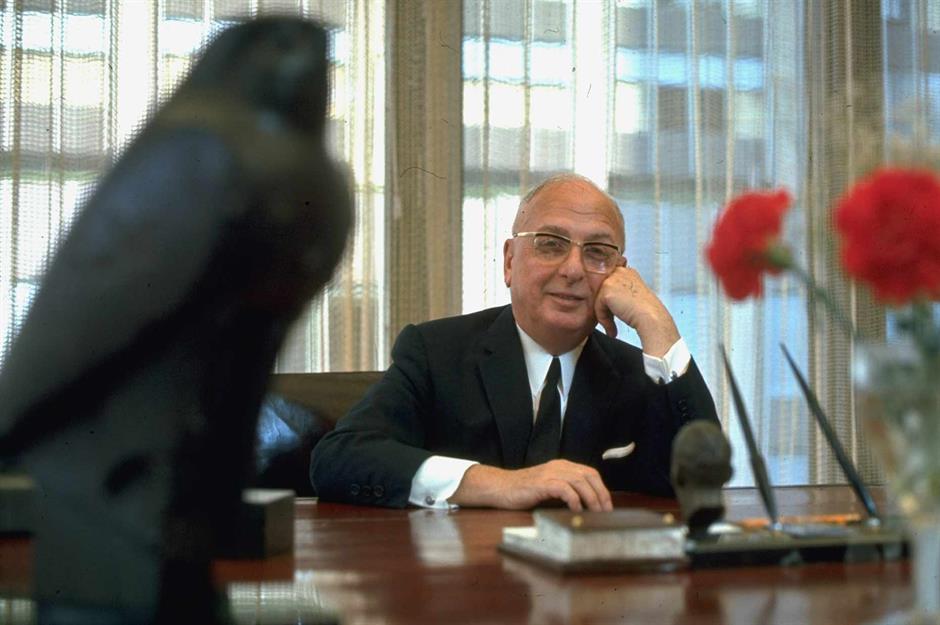

Samuel Bronfman

The son of poor Jewish immigrants who fled persecution in czarist Russia, Samuel Bronfman (27 February 1889 – 10 July 1971) established his family’s fortunes when he acquired the Seagram Liquor Company in 1928.

From his business interests, Bronfman built several financial empires, as well as investing generously in charitable organisations, including the World Jewish Congress and the Canadian Jewish Congress, for which he also served as president.

The head of a vast, multigenerational clan, Bronfman’s descendants proudly carry on the family name, its business pursuits and charitable interests.

The Bronfman Estate, Montreal, Quebec

With their spectacular fortunes, it should come as no surprise that the Bronfmans built up an impressive property portfolio. One of their most prominent residences was this brick home in Westmount, Montreal, which sits near the summit of a mountain of the same name.

The home was originally built in 1906 for George Sumner, the former president of the Montreal Board of Trade, but his heirs sold it to Samuel Bronfman in 1928.

The Bronfman Estate: creating a family compound

In 1929, Samuel and his wife Saidye began making changes to the home, first consulting the original architect for advice, before commissioning architects Hutchison & Wood to improve and expand the property.

Bronfman’s brother went on to purchase the house to the east and together they purchased the home in the middle, which they demolished to create a formal shared garden. Samuel and Saidye are pictured here enjoying a stroll in the new grounds in 1966.

The Bronfman Estate: historic features preserved

Between 1938 and 1973, Samuel and Saidye commissioned at least six further extensions on the home to keep pace with their growing fortunes and family. Today, the home stands on 1.5 acres (0.6ha) and is still under the ownership of the Bronfman family.

In spite of the many renovations and expansions, much of the original architecture and interiors remain, including the original wood panelling in the dining room and study, where the couple were captured here in 1966.

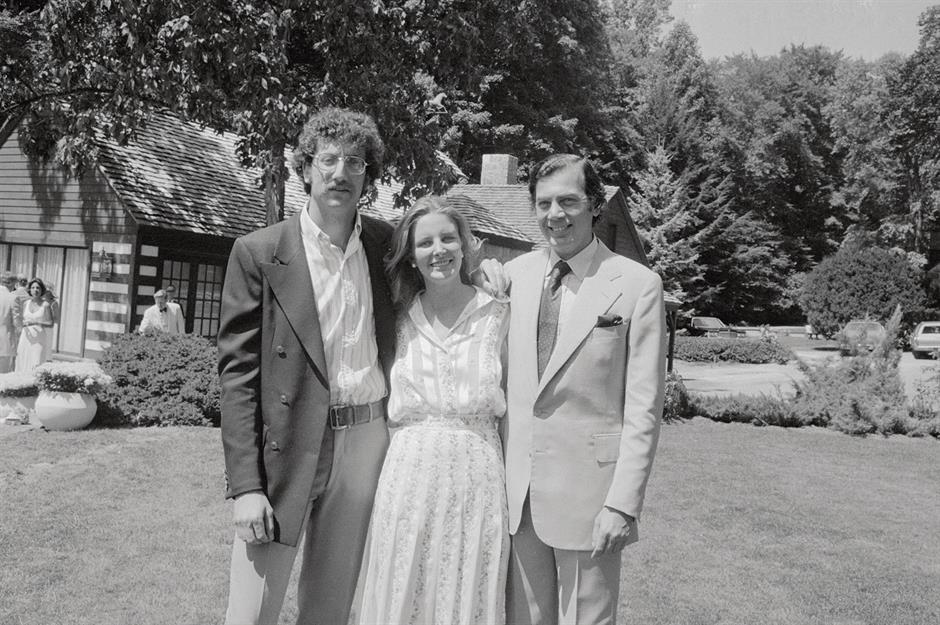

The Bronfman Estate: a gathering place for future generations

In both the dining room and the drawing room, large windows offer beautiful views out over the St. Lawrence River and the shared family garden, which has served as a formal and informal gathering place for the clan over the years.

Pictured here, Samuel Bronfman II (Bronfman’s grandson) poses with his father, Edgar M. Bronfman, and his bride following their wedding on the family estate in 1975.

Loved this? Now discover more amazing historic homes

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature