Archive photos show German home life through the decades

100 years of German homes in vintage pictures

Home life in Germany has seen remarkable changes over the past century, shaped by shifting social trends, economic developments and cultural influences.

From close-knit rural households in the 1890s to bustling urban apartments, post-war recovery efforts, GDR Plattenbau apartment blocks and modern family dynamics, everyday domestic life has constantly evolved.

Click or scroll to explore how domestic life in Germany has transformed through fascinating archive photographs...

1890s: a traditional inn in Nuremberg

In the late 19th century, Germany was undergoing a significant social change. As urbanisation accelerated, people left rural areas to make their home in rapidly growing cities like Berlin, Munich and Hamburg. This shift brought a rising working class that pushed for better wages and improved conditions.

In response, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck introduced social welfare programs to maintain stability. Middle-class Germans increasingly visited cafés and restaurants to enjoy lively discussions, music performances and popular dishes like schnitzel.

Pictured here is the Bratwurstglöcklein Inn and its staff in Nuremberg around 1890.

1894: the birth of the automobile

Outside of the domestic sphere, Germany's transformation into a major economic power was driven by rapid industrial growth, with key sectors like steel, coal, and chemicals expanding dramatically. This industrial surge fuelled technological advancement across the country.

A defining moment came in 1885 when Carl Benz invented the Benz Patent-Motorwagen, the world's first practical automobile. This ground-breaking achievement revolutionised transportation and marked the birth of the modern automotive industry.

Carl Benz is shown with his family and his Benz Velo in the Mannheim factory yard.

1898: a house in rural Bavaria

The Print Collector via Getty Images.jpg)

Rural Germany remained deeply rooted in agriculture despite the country's rapid industrialisation. Families worked small plots of land or served on larger estates, relying on traditional farming practices with manual labour and horse-drawn equipment. Economic hardship forced younger generations to migrate to cities for factory work.

Despite this urban migration, village life preserved its strong social cohesion, centred around family ties, church communities, local customs and traditions, and the seasonal rhythms of agricultural work.

These Bavarian mountaineers, pictured here in 1898, lived a more traditional life.

1900s: a thatched house in the Black Forest

This photo, taken between the 1890s and 1900, shows a traditional Black Forest farmhouse in Baden, Germany. These wooden, thatched homes date back to the 1600s and earlier – a similar example still stands in the Black Forest Open-Air Museum.

The steep roof, designed for snowy conditions, provides ample attic space for storing hay. Inside, timber walls, ceilings and floors are finished with panelling, shiplap and cladding. Open coal fires served both for heating and for smoking hams, a regional speciality still made today.

1900: small town life

Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo _ Alamy Stock Photo-2.jpg)

Small towns maintained a middle ground with local industries and trades, established market squares and strong community bonds. They combined some modern conveniences with traditional social structures that centred around churches and local governance.

As the century rolled on, many men were called to the front during the First World War, leaving women, children and the elderly to manage farms and businesses. Wartime shortages and rationing deeply affected these communities, which added strain to their daily lives.

Pictured here are two little girls in the Bavarian town of Ochsenfurt in 1900.

1905: women in the workforce

As industrialisation advanced into the 20th century, traditional gender roles shifted and women increasingly took on jobs in factories, offices, agriculture and more. They managed households while contributing to essential industries, gaining new responsibilities and some independence.

Although they still made up a relatively low percentage of the total workforce, this period marked a significant step toward women's social and economic empowerment and laid the groundwork for future advances in gender equality in Germany.

This photo shows three female window cleaners in the streets of Berlin.

1926: Bauhaus influence

Modernist influences during the interwar period (1919-1938) transformed housing design, with architects such as Walter Gropius and the Bauhaus movement promoting functional, minimalist structures that aimed to provide affordable, efficient living spaces for the growing population. Many of their timeless designs, such as tubular metal chairs and plywood furniture, are still popular today.

In 1926, architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky designed the Frankfurt Kitchen (pictured right), thought to be the forerunner of modern fitted kitchens and leagues ahead of its time.

1928: modern apartment blocks in Frankfurt

Homes transformed rapidly in the early 20th century. In the 1920s, architect Ernst May led a team that designed 12,000 modernist apartments in a pioneering urban project known as 'New Frankfurt'. The development was condemned as “un-German” by the far right, with Joseph Goebbels dubbing May the “Lenin of German architecture”.

When the Nazis took power in 1933, construction stopped. May left for the Soviet Union, joining Le Corbusier and former Bauhaus members in seeking new opportunities abroad.

1930: a girls' boarding school

Though Germany faced economic instability, with hyperinflation in the 1920s and the Great Depression later impacting families, education for children evolved. As Nazi influence grew the focus shifted to discipline and national values in particular.

Schools increasingly promoted ideological teachings, shaping youth to align with state goals. Changing family dynamics significantly influenced everyday life during this period.

Shown here is a room in a girls' boarding school, probably Wilhelmstal Castle, in 1930.

1943: women work in the fields

With men drafted to war, women were called upon to fill positions previously reserved for men. They worked in factories, producing weapons, ammunition and war supplies, and also took on roles in agriculture, healthcare and transportation.

Despite these new responsibilities, Nazi ideology still placed great emphasis on women's traditional roles as wives and mothers. Women were expected to prioritise domestic responsibilities – raising future soldiers and household management – even as wartime demands pulled them into the workforce.

This image depicts women working in agriculture in 1943.

1945: women repurpose war items

Germans addressed household supply shortages by creating their own solutions. Military blankets were skilfully repurposed into warm coats, jackets and baby clothes to help families endure harsh winters. Old uniforms were carefully dismantled, with the fabric used to sew curtains, tablecloths or patchwork quilts.

These pictures from September 1945 show saucepans being manufactured from the thousands of helmets which littered the streets. Pictured right, a housewife uses one of the completed helmets in her kitchen, on the left a worker operates a hand press cutting away the rim.

1945: rubble women clear debris

Following the war, cities like Berlin, Hamburg and Dresden lay in ruins. Rebuilding began almost immediately, requiring immense labour to clear debris and restore infrastructure.

Due to the absence of men who had been killed or held as prisoners of war, women became central to the recovery process. Known as Trümmerfrauen (rubble women), they took on the physically demanding task of clearing debris from bombed-out buildings, forming human chains to salvage and pass materials for reuse in reconstruction efforts.

This photo from 1945 depicts the removal of rubble and recovery of building materials Rubensstraße, Berlin.

1949: Germany splits

dpa picture alliance _ Alamy Stock Photo-2.jpg)

In 1949, Germany split into two countries: the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG or West Germany) and the German Democratic Republic (GDR or East Germany). Both faced devastation and severe housing shortages; many families lived in overcrowded emergency shelters like huts and barracks.

Resources were scarce, and rebuilding efforts were slow. Many people were grieving and traumatised as the true horrors of the war became more widely known. Over time, communities restored homes, schools and businesses, allowing daily life and a sense of normality to gradually return with resumed schooling, markets and social gatherings. Even celebrations like Christmas gave some a sense of normality.

1953: a fridge delivery

INTERFOTO _ Alamy Stock Photo.jpg)

Beginning in the early 1950s, West Germany experienced remarkable growth known as The Wirtschaftswunder, or "economic miracle”. It was driven by currency reform, the Marshall Plan and industrial innovation.

Under Chancellor Konrad Adenauer and Economics Minister Ludwig Erhard industries thrived, unemployment dropped and living standards improved. Consumer goods became widely available, and cities were rebuilt, transforming Germany into one of the world's leading economic powers by the late 1950s.

Pictured here is an advertising postcard for fridges in 1953.

1953: a refugee camp in West Berlin

Associated Press _ Alamy Stock Photo.jpg)

In the 1950s and early 1960s, thousands fled East Germany to escape political repression, economic hardship and limited freedoms under communist rule. Berlin became the main escape route, and by 1961 around four million people had moved west.

The exodus heightened Cold War tensions and led East Germany to erect the Berlin Wall to halt the flow. This photo, taken in January 1953, shows East German refugees at the Karlsbad camp in West Berlin, crowded into temporary quarters used for sleeping, cooking and washing.

1954: a 'show home' in East Berlin

East Germany struggled economically under Soviet influence, adopting a centrally planned system that prioritised heavy industry over consumer goods. Daily life was marked by shortages, low wages and restricted trade with the West. Strict state control stifled growth and fuelled unrest, including the 1953 workers’ uprising, which saw mass strikes and violent clashes.

This 1954 photo shows the living room of the Hegemann family in East Berlin’s Stalinallee – then a Communist showpiece – captured during a rare visit by Western journalists permitted by Russian authorities.

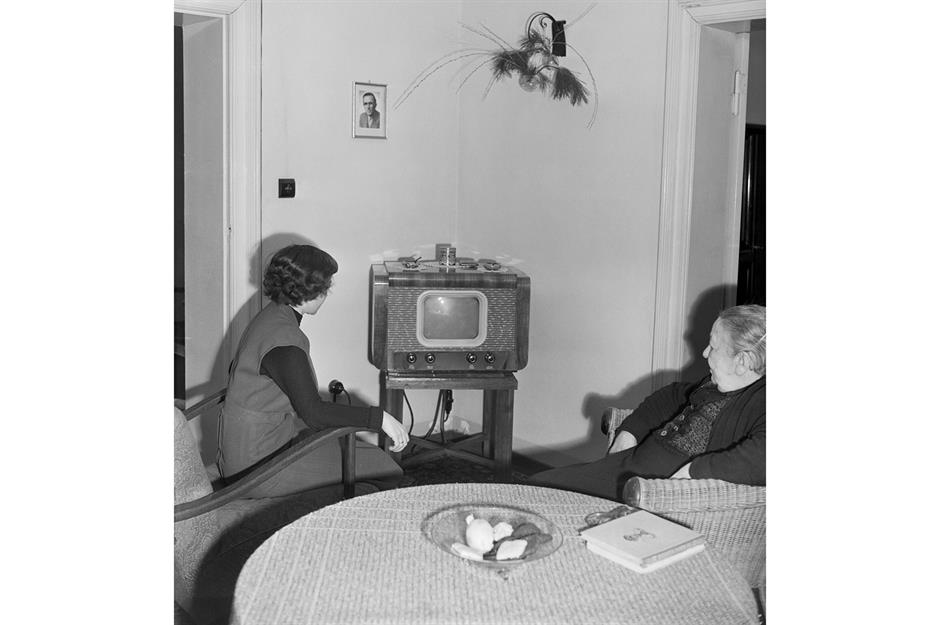

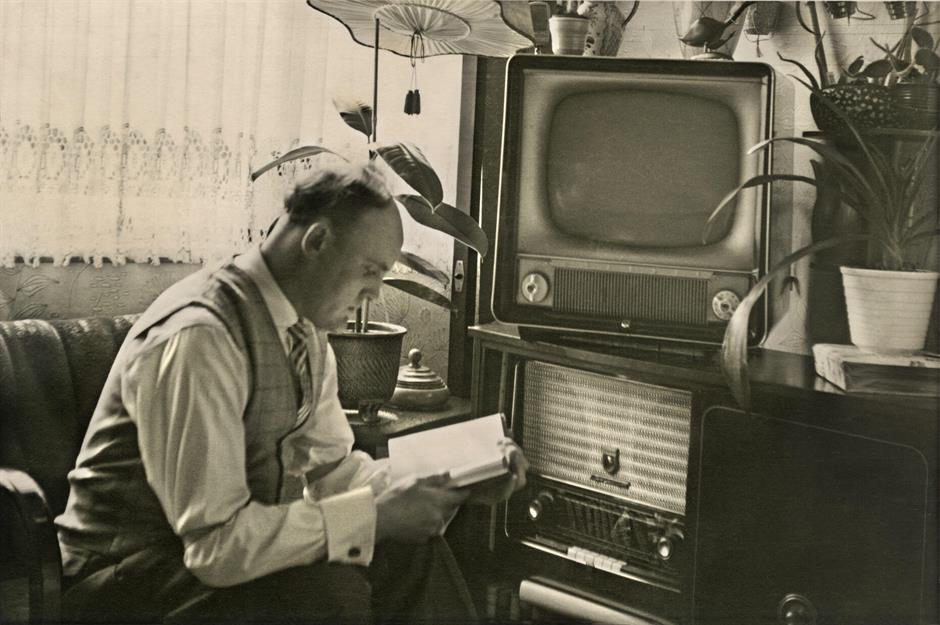

Late 1950s: TVs enter the home

Modern appliances flourished in West German homes during the post-war Wirtschaftswunder. Washing machines, refrigerators and vacuum cleaners eased household chores, while television sets emerged as symbols of prosperity. By the 1960s, family evenings gathered around the TV were common, with news and entertainment programs shaping cultural trends and strengthening national identity.

Depicted here is a man with a Grundig TV set in Bochum, around 1957.

1962: GDR manufactures own goods

As the 60s rolled on, East German homes also gradually acquired modern appliances, although these remained less available than in West Germany.

Household appliances like washing machines and radios became more common and improved domestic life. Television sets also spread, with state-controlled broadcasts promoting socialist values.

This picture shows advertising for RFT television sets, East Germany, circa 1962.

Late 1960s: a house in the suburbs

This picture shows German television and radio presenter Carlheinz Hollmann with his wife Gerti Daub, the former Miss Germany, and their two children at the swimming pool in front of his house in Hamburg around 1969.

The rise of suburban homes provided middle and upper-class families with more space, gardens and modern amenities. Improved infrastructure and car ownership facilitated this development. Those who couldn't afford to build or buy a house might opt for a Schrebergarten (a small, private garden plot), often with a summerhouse built on it, for gardening, relaxation and social activities.

Late 1960s: a Plattenbau apartment block

Life in East Germany was shaped by state-planned housing and collective living, particularly in Plattenbau apartment blocks. These prefabricated concrete buildings addressed housing shortages with basic, uniform living spaces.

Though functional, they emphasised socialist community values through shared courtyards, childcare facilities and social hubs. Housing was assigned according to family size, reflecting the regime's centralised control over domestic life.

The photo was taken in East Berlin between 1965 and 1971.

1971: consumer culture in West Germany

In post-war West Germany, rising incomes and economic stability fuelled a thriving consumer culture and integration into global consumer trends.

The iconic Volkswagen Beetle symbolised newfound freedom and enabled international travel, with holidays to Italy, France and Spain becoming increasingly accessible. Western consumer goods – including fashion, electronics and household appliances – flooded the market.

A model demonstrates a recliner chair made from the bonnet of a Volkswagen Beetle.

1974: a typical GDR home

In contrast, GDR life was characterised by economic constraints, with coffee, bananas and fashionable clothing often scarce. The Trabant, East Germany's famous car, was notorious for its long waiting lists – sometimes delivered years after ordering.

East German products, while functional and durable, lacked Western variety and quality. From 1962, the unique Intershop chain offered coveted Western goods including clothing, electronics, cosmetics, alcohol, cigarettes and food items – a rare glimpse of capitalist abundance within the socialist state.

At home with radio mechanic Manfred Spranger and his family in East Berlin, 1974.

1975: a woman at home in Oberhausen

In the 1970s, nearly half the women in West Germany were part of the workforce. However, many of these jobs were part-time or in lower-paid sectors. Despite this increase in working women, a significant portion (roughly 50 to 60%) remained housewives, especially among married women with children. Traditional gender roles were still common, with women often balancing domestic duties alongside employment.

It was only in 1977 that women were given the right to work. Before then, the Marriage and Family law of the FRG stated that: "The wife is responsible for running the household. She has the right to be employed as far as this is compatible with her marriage and family duties."

Late 1970s: working women

Tassilo Leher _United Archives via Getty Images.jpg)

By the 1980s, around 90% of working-age women in East Germany were employed – one of the highest rates in the world. The socialist state promoted gender equality in the workforce, encouraging women to work in industry, healthcare and education.

Support systems such as childcare, maternity leave and workplace policies helped women balance careers with family life. Employment was seen as part of a woman’s civic duty in the GDR. This photo shows East German actress and Brecht interpreter Gisela May in a flat around 1976.

1985: access to consumer goods

West Germany experienced a period of growing middle-class prosperity, with improved living standards and modern conveniences. Many families enjoyed spacious suburban homes, and car ownership was widespread, with popular models like the Volkswagen Golf and Mercedes-Benz becoming common household staples.

Keeping pace with the UK and the USA, shopping malls and department stores like Karstadt and Kaufhof provided access to a wide range of consumer goods. Kira von Preussen and her daughter are pictured preparing a meal at home in Bad Kissingen.

1990: new groceries in the kitchen

German reunification followed the fall of the Berlin Wall on 9 November 1989. This pivotal moment marked the start of East and West Germany’s path to reunification. On 1 July 1990, the Deutsche Mark was introduced in the former GDR, replacing the East German mark and integrating the region into West Germany’s stronger market economy.

This picture from 3 July 1990 shows East German housewife Astrid Wagner and her daughter Mandy unpacking groceries at home. It marks the first time they had bought Western supermarket products with the new official currency.

1990s: two countries become one

Merging East and West German cultures after reunification was a complex process. West Germany’s consumer lifestyle and focus on individualism often clashed with East Germany’s collectivist values and state-run systems.

Housing in the East was often more basic – this photo of Berlin’s Rykestrasse shows a coal vehicle making deliveries, as many GDR apartments were still heated with briquettes. Differences extended to work habits, social norms and language. Yet shared traditions, music and sports helped bridge the cultural divide and foster a sense of unity.

Loved this? See more amazing archive photos of homes from the past.

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature