Explore Oneida: an 1800s mansion built to house a historic religious commune

Welcome to Oneida

In the late 19th century, in this impressive New York State home, the utopian Oneida Community thrived for 30 years. This implausible Protestant Perfectionist community had hundreds of members; worldly possessions were universal, living quarters were shared, and everyone in the society raised their children.

The Oneida Community Mansion House holds many stories and has since been restored to its former glory after an extensive renovation.

Click or scroll to learn more about this remarkable community and the building they called home…

The birth of a community

Born of the late 19th century Protestant revival known as the Second Great Awakening, the Oneida Community in central New York was an idealistic community of Perfectionists, and arguably the most successful commune in American history.

Oneida residents shared everything, from living quarters and possessions to sexual partners, and at their height, the community numbered about 300 members, all packed together in this sprawling 93,000-square-foot (8.6k sqm) brick mansion.

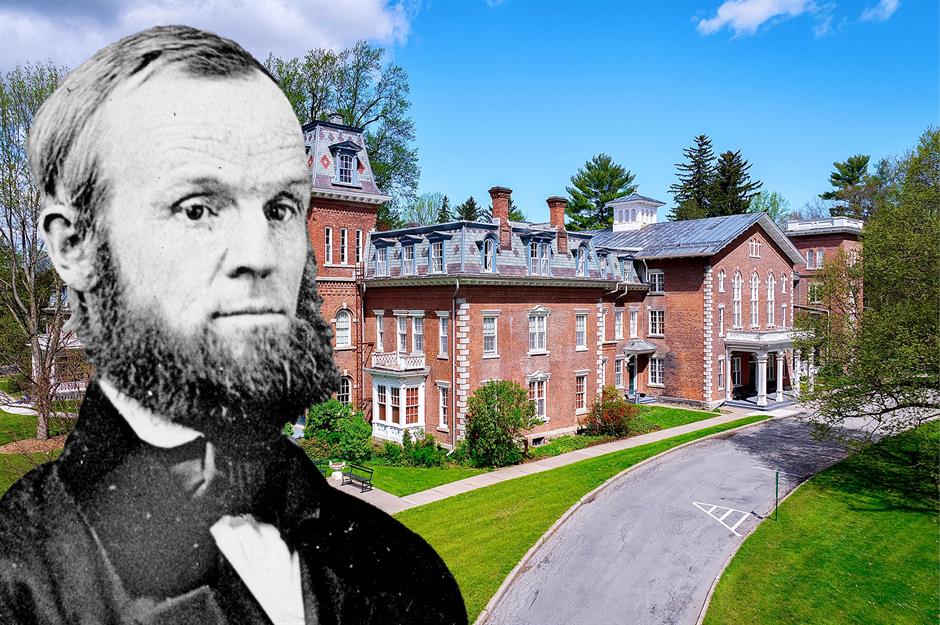

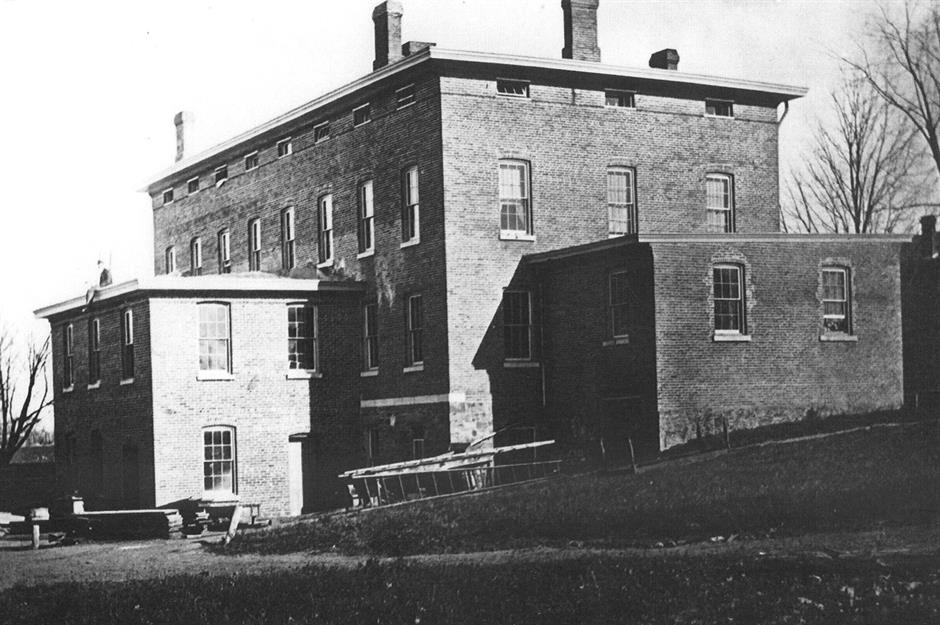

Here we see the Oneida Community Mansion House around the 1860s.

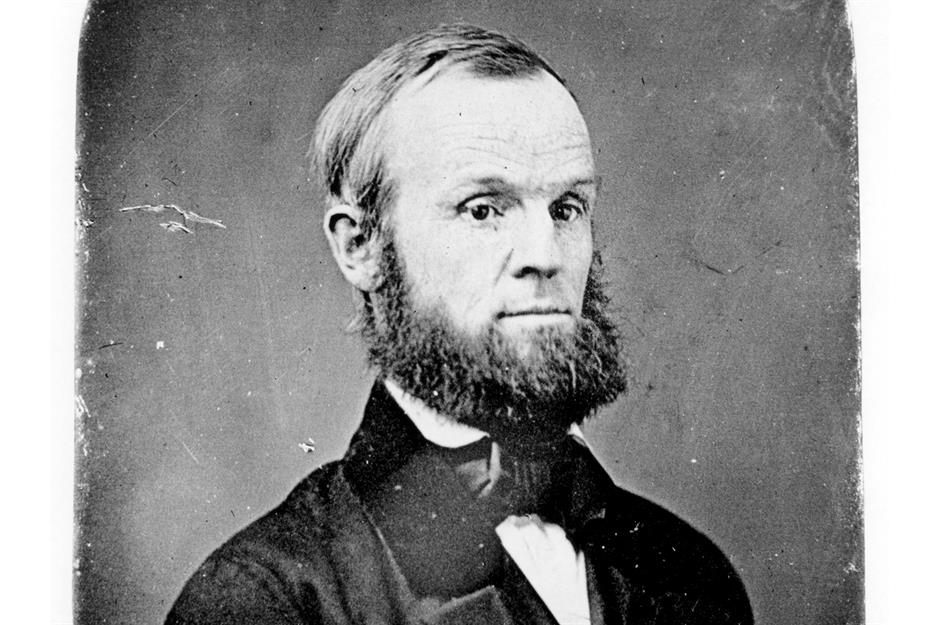

John Humphrey Noyes

The commune was founded in 1848, in Oneida, New York, by the charismatic, Vermont-born John Humphrey Noyes. He assembled a legion of followers united by the belief that Jesus had already returned in AD 70.

Noyes believed that people could bring about Heaven on Earth through a combination of communal living, an unconventional family structure in which all men and women were married to one another and by raising children in common.

By 1878, the Community’s original 87 members had grown to 306, while branch communities sprang up in Wallingford, Connecticut; Newark, New Jersey; and Putney and Cambridge, Vermont.

A new Eden

Oneida members embraced the communalism of the early Christian Church, attempting to create their new ‘Eden’ through the formation of a more rational, just and moral society.

This included the application of concepts, including 'complex marriage', a system of free love wherein all members were permitted to have sex with any other consenting members, and 'mutual criticism,' meaning every resident was subject to criticism by the Community as a whole.

The goal of the latter was to eliminate 'undesirable' character traits.

An ongoing construction project

The Mansion House itself was largely designed communally by Oneida members, who hired outsiders to construct the Mansion House in 1862.

The structural design was theoretically communal, in an effort to reinforce the idea of a shared lifestyle, family and belief system. It also meant that the home would be communally owned, the shared holding of the property cementing the Oneida concept of group marriage.

Meet the architect: Erastus Hamilton

However, while this was a good idea in theory, some practical expertise was required to bring the project to fruition, and the Community turned to one of their own, architect Erastus Hamilton, pictured here, as their lead builder.

Hamilton had experience and knowledge in both engineering and architectural trends and was able to successfully execute the Community members’ vision for the property.

Communal construction

The Mansion House's construction was something of an ongoing project over the following 20 years, as architectural tastes changed and the needs of the Community evolved.

The original 1862 brick structure was built in the Italianate Villa style popular at the time, but by the late 1860s, the increased number of children in the house necessitated the construction of the South or Children’s Wing, which was built in the French Second Empire Style.

This was an eclectic architectural style, mixing European trends, most notably the Baroque, often combined with mansard roofs and low, square-based domes.

Expanding the house

In response to further membership expansion in the late 1870s, the Community commissioned the addition of the 'New House', built in the contemporaneously popular Gothic Revival style.

Supplemental structures were added as needed, including the Tontine pictured here, which was built in 1863 to house laundry facilities, kitchens and other light industry.

Community spaces for communal living

Inside, the Mansion House's interior was designed to reflect the ideals of shared space and constant socialisation (key parts of communal living). All spaces were consequently designed to facilitate mingling in large groups.

The Upper Sitting Room, pictured here, had two storeys and featured a balcony, large windows and a lavish collection of comfortable furnishings.

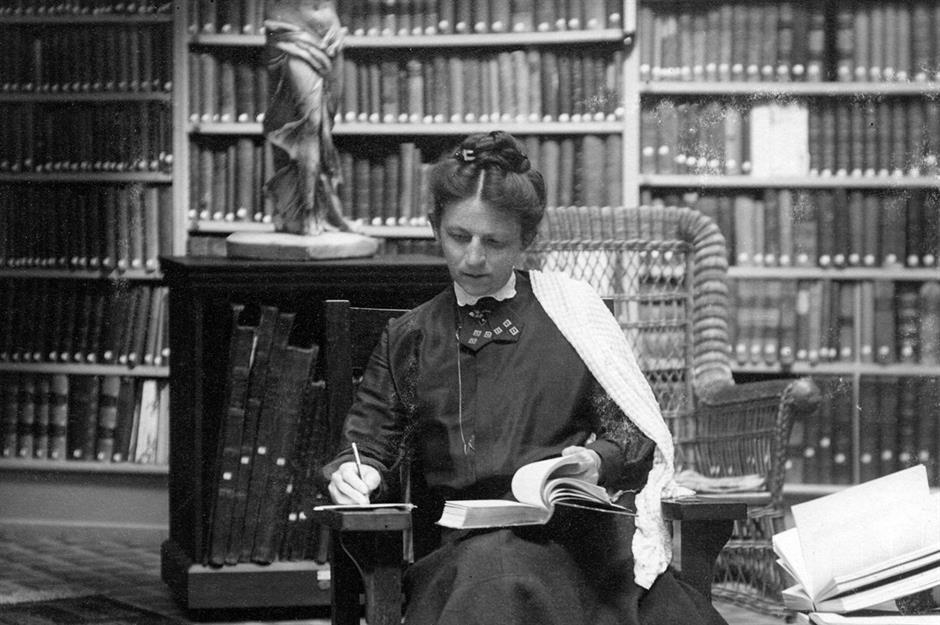

An impressive library

Another popular communal gathering place, the Mansion House library boasted nearly 3,300 volumes, making it one of the largest and best-stocked of its kind in America at the time.

The eclectic collection boasted titles ranging from Darwin’s Origin of Species to Wiley’s Elocution and Charles Dickens’ Mystery of Edwin Drood.

What's more, it provided a rare environment where men and women could study Latin, Greek, algebra, astronomy, literature and art together. Uncommon at the time, but not at Oneida.

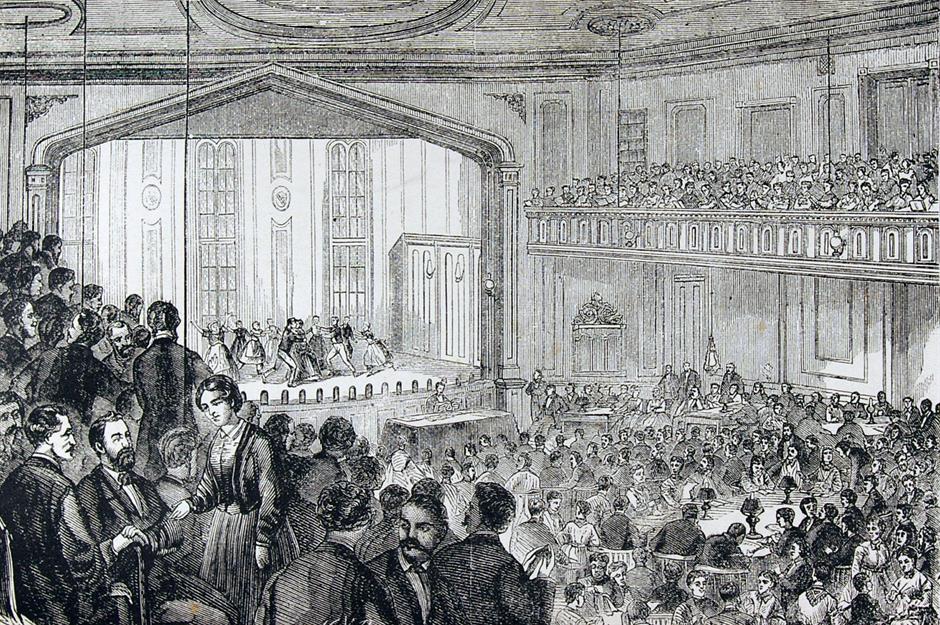

The Big Hall

The epicentre of the Mansion House, pictured here in an etching, was the Big Hall, where the Community gathered each night to enjoy entertainments ranging from musical performances and plays to Bible readings and preachings from John Humphrey Noyes.

Reminiscent of a Victorian music hall, the spectacular two-storey hall featured a wrap-around balcony, a central stage backed by three large windows and a trompe l’oeil ceiling featuring figures representing the Greek muses.

Feeding the community

Feeding a Community of 300 was, understandably, an enormous undertaking, and the kitchens at the Mansion House were well stocked with plenty of equipment, utensils and storage containers, not to mention numerous cooks to meet the commune’s daily culinary needs.

The Dining Room also housed large tables for community-style dining, or in fine weather, members of the Community could dine picnic-style on The Quad, as can be seen here.

Work and play

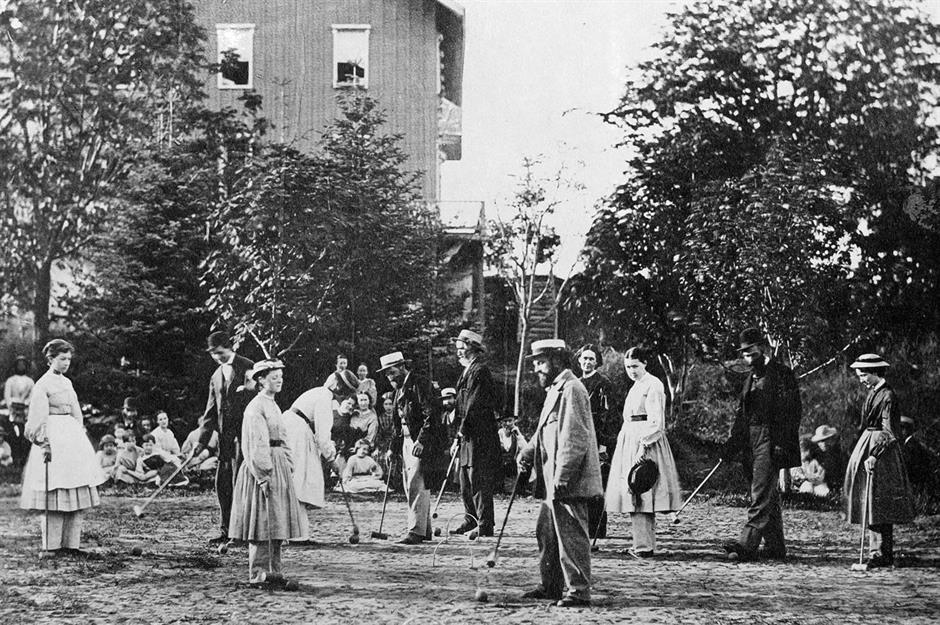

Hard work in support of the Community was an important part of life at Oneida. Community members farmed, canned fruits and vegetables and produced goods like silk thread, travel bags, brooms, chains, rustic seats and most profitably, steel animal traps and silverware.

However, life at Oneida was far from all work and no play. Community members are pictured here enjoying a game of croquet on the lawn, a popular pastime enjoyed by the commune when daily chores were finished.

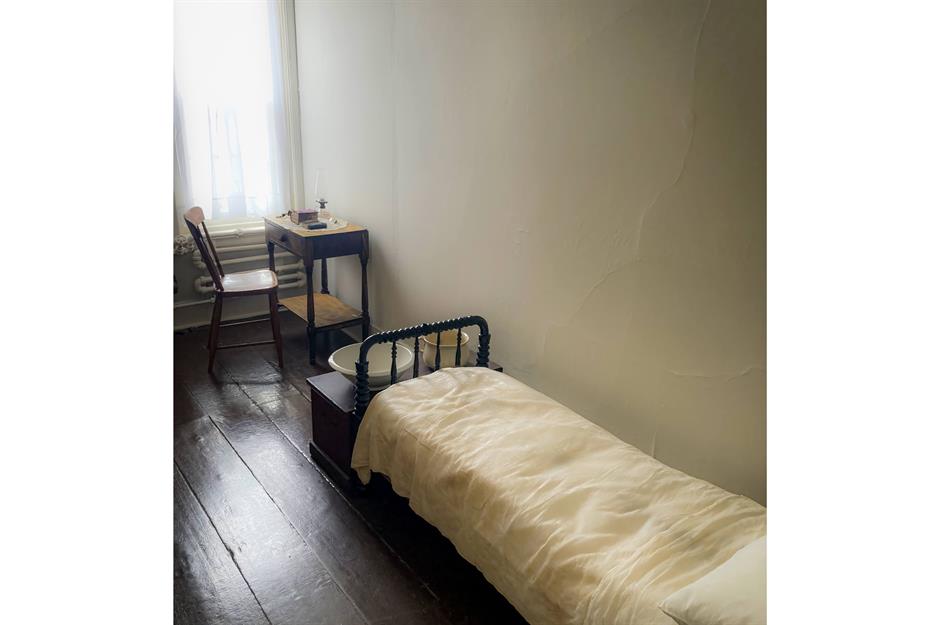

Small and simple bedrooms

On its upper stories, the house boasted dozens of bedrooms, which, unlike its lavishly appointed living spaces, were incredibly plain, with simple furnishings and single beds, almost like a traditional monk’s cell.

The theory behind this layout was to remind residents that the bedroom was not a private sanctuary, but rather a utilitarian space that was part of a larger family home.

The complications of 'complex marriage'

It was this very lack of privacy and family autonomy which was the ultimate downfall of the Oneida Community. The concept of the 'complex marriage' was a core tenet of the Community, Noyes having decreed: “The new commandment is that we love one another, not by pairs, as in the world, but en masse."

The theory was that the complex marriage would eliminate jealousy and allow more sexual freedom for both men and women. But this did not unfold as Noyes planned...

An experiment gone wrong

As Noyes became more zealous in his beliefs in the early 1870s, his followers became less enamoured of his philosophy.

Prompted by Noyes, in 1869, the Oneida Community began an experiment in eugenics which they dubbed “stirpiculture,” a selective breeding process where couples were chosen by a committee based on their spiritual qualities.

While 58 children were produced through this method, the experiment was undermined by mounting desires for monogamous love and parental feelings.

The end of Oneida

The experiment caused many to leave the Community of their own volition, spelling the beginning of the end for Oneida.

The true capstone, however, came when John Humphrey Noyes attempted to pass the leadership of the Community to his son, Theodore, who lacked both his father’s leadership skills and the fervour of his beliefs.

This, combined with mounting pressure and protest from the external local community, finally led to the breakup of the commune in 1879.

What happened next?

The commune’s silverware business and other holdings were reorganised into a joint-stock company, which under the name Oneida Ltd., is one of the most recognised names in silverware today.

After the breakup of the commune, the Mansion House remained a private home and symbolic company headquarters for about 106 years, though the memory of the Community was alive and well.

Pictured here in 1948, a group of girls dressed up in the original Perfectionist 'Short Dress' to celebrate 100 years since the original Community members arrived in Oneida.

Preserving the Mansion House

Meanwhile, the Mansion House itself was transferred to a private nonprofit organisation: Oneida Community Mansion House (OCMH).

Oneida Ltd. had been experiencing significant financial challenges before its demise and required necessary repairs.

However, in 2019, the Board of Trustees conferred with historical preservation architects and decided to undertake a major, multi-year restoration and preservation of the building, with estimated costs of $10 million (£7.5m), starting with a $2 million (£1.4m) Phase 1 Preservation Project.

A whole new outlook

The first phase of the restoration principally involved the building’s roof, addressing leaks and deterioration by replacing all roof tiles and cornicing along the mansard roof.

The brick facade was also repaired and rebuilt with historic bricks and lime mortar to match the original, and a new water management system was installed.

How the OMCH operates today

Today, OCMH is still preserving the Mansion House while fundraising for Phase 2 of the operation.

But, it is also still open to the public as an active museum and non-profit educational organisation chartered by the State of New York, offering events for school groups, tours, lectures, art workshops, concerts and rentable event space.

There is also a collection of overnight guest rooms and residential apartments, as the Mansion House continues to welcome visitors who want to experience a stay in the former home of the Community.

What's next for the OMCH?

The Big Hall has been protected and today hosts a range of musical performances, lectures, and corporate and family events.

A National Historic Landmark, the Mansion House aspires with the next phase of the restoration to deepen and diversify its function as an educational resource, historic inn and event space.

Staying at Oneida

Today, OCMH welcomes history buffs, students, researchers, vacationers and descendants of original Community members to see how the world’s most successful commune really lived.

For a stay in one of the fourteen guest rooms, accommodations include a private room, a simple breakfast and a tour of the museum and hundreds of acres (13ha) of landscaped grounds and gardens.

The future of Oneida

Curiously, the lure of Oneida’s unconventional Community still endures nearly 180 years after its initial founding.

With Phase 2 of the restoration process being planned, the Oneida Mansion House will be in operation for many years to come, serving as a unique opportunity to visit and stay overnight in a National Historic Landmark and museum.

Loved this? Now discover more incredible historic homes

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature