America’s most incredible mansions that don’t exist today

The Gilded Age homes that didn’t survive

While reminders of the Gilded Age linger in the form of museums and architectural landmarks across America, some of the most grandiose homes ever built have long since been demolished.

These impressive buildings now only exist in faded archive photographs and historical records. We've uncovered the palatial residences of the so-called robber barons, the Vanderbilts, the Astors and the Carnegies, whose wealth and influence transformed the country in the late 19th century.

Click or scroll on as we unearth a bygone age of inconceivable wealth and opulence...

Vanderbilt Triple Palace, New York

The Vanderbilts were one of the richest families in American history, and their mansions lined Fifth Avenue, New York.

In 1882, William Henry Vanderbilt, the eldest son of Cornelius 'the Commodore' Vanderbilt, who founded the family fortune, bought an entire block on Fifth Avenue between 51st and 52nd Street, building three mansions for himself and his wife and his two daughters, Emily and Margaret.

Designed by J.B. Snook and known as the Vanderbilt Triple Palace, the idea was to clad the palazzo-style buildings in Italian white marble, but William opted for the faster local brownstone route due to his declining health.

Vanderbilt Triple Palace, New York

Between the mansions was a courtyard leading to a shared square entrance hall of 1,296 square feet (120sqm) with mosaic walls and a stained-glass skylight.

William and his wife lived at 640 Fifth Avenue, which had 58 rooms, including this ornate drawing room featuring walls clad in mother-of-pearl inlay and a ceiling mural by Pierre-Victor Galland, a leading decorative painter of the time.

Sadly, the entire complex was eventually sold off, in part to Vanderbilt rivals, the Astors, and demolished to make way for skyscrapers.

Cornelius Vanderbilt ll mansion, New York

Around the same time in 1882, William’s son, Cornelius Vanderbilt II, a favourite grandson of Cornelius Vanderbilt, made his mark on New York by building the city's largest and most opulent home.

Designed by Beaux Arts architect George B. Post and located on the corner of Fifth Avenue and 57th Street, the Renaissance-style château boasted 130 rooms, several ballrooms and numerous libraries and parlours.

Cornelius Vanderbilt ll mansion, New York

After the mansion’s completion in 1883, Cornelius commissioned the finest artisans to decorate the interiors, seen here in the Grand Salon, which was designed by Jules Allard et Fils.

A stunning mantelpiece by Saint-Gaudens, which once graced the entrance hall, can be seen today in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The house eventually became too big for Cornelius’s widow Alice after he died in 1899. It was sold for $7 million in 1926, which would be around $126 million (£95m) in today's money. In its place stands the Bergdorf Goodman department store.

William K Vanderbilt’s Petit Château, New York

It was clearly a race to the top, because at almost the same time in 1882, Cornelius Vanderbilt II's younger brother, William Kissam Vanderbilt, and his social-climbing wife Alva, set about building a sensational château-style mansion at 660 Fifth Avenue.

Clad in pristine white limestone, the dreamlike French Renaissance and Gothic-style home, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, quickly eclipsed other mansions on the block, elevating the couple and the family to the pinnacle of New York society.

William K Vanderbilt’s Petit Château, New York

Known as the Petit Château, its interiors were dazzling, filled with treasures from across Europe. Highlights included a Gothic-inspired banquet hall and this Jules Allard et Fils salon, which had a painted ceiling and an ebony secretary bureau that once belonged to the ill-fated Queen Marie Antoinette of France.

Sadly, the mansion was sold following William K’s death in 1920 to a banking trust, before eventually being replaced by a multi-storey office block.

Mrs William B. Astor’s house, New York

Having spent most of her adult life in a mansion-size brownstone on the corner of 34th Street and Fifth Avenue, where she held her famous 'Four Hundred' annual ball for the cream of New York society, Caroline Astor, the wife of businessman William Backhouse Astor Jr, moved up the avenue towards the new Central Park in 1896 to a new much larger house on the corner of 65th Street.

One side of the double mansion, designed by Richard Morris Hunt in French Renaissance style, was occupied by the so-called 'The Mrs Astor', while the other was for her only son, John Jacob Astor IV and his family.

Mrs William B. Astor’s house, New York

The beautifully crafted interiors were French in style. The entertainment rooms of each house, not least the opulent ballroom for 1200 guests, were designed so they could be combined into one space.

The ballroom doubled as a picture gallery and featured enormous carved female figures beneath a stained-glass skylight.

John Jacob famously died on the Titanic in 1912, and the collection was sold off at auction in 1926. The house was later demolished. In its place stands the Temple Emanu-El.

Mark Hopkins Mansion, California

One of the so-called 'Big Four' in San Francisco in the late 19th century, Mark Hopkins was one of the founders of the Central Pacific Railroad. He joined his fellow millionaires on fashionable Nob Hill when he set about building his Gothic-inspired mansion.

Sadly, he never actually lived there since the spectacular residence was not completed until after he died in 1878. He died about a week after seeking a health cure in the Arizona desert.

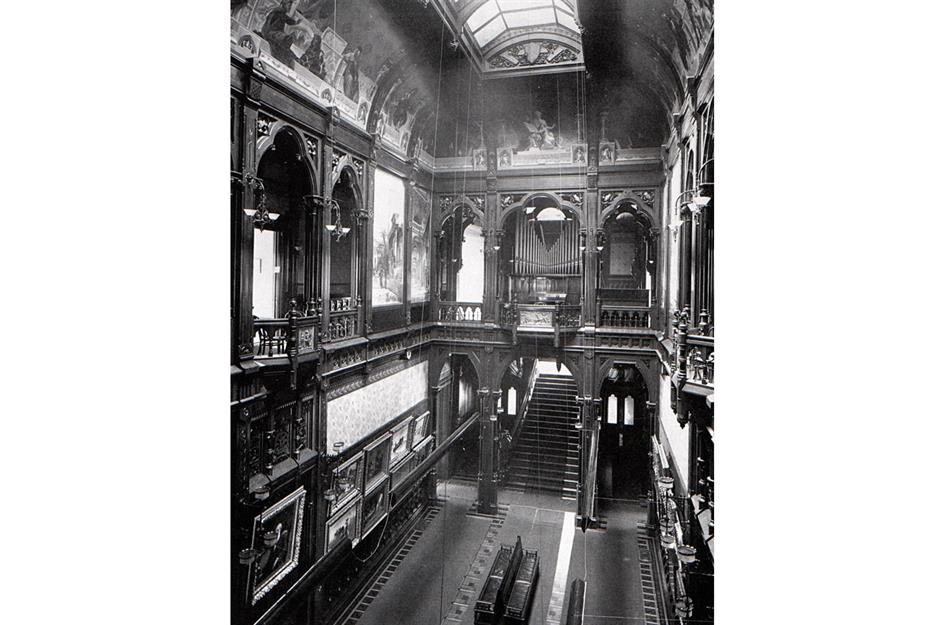

Mark Hopkins Mansion, California

Like many mansions of its time, it had a multi-storey entrance hall with a dramatic staircase. The dark, rather industrial-looking space was illuminated by a vast skylight, which highlights the owner’s extensive art collection.

Mark Hopkins’ widow, Mary, left the estate to her second husband, Edward Francis Searles, on her death in 1891. He left the building and grounds to the San Francisco Art Association.

The house survived the 1906 earthquake, which devastated the city, but tragically was destroyed in a fire just days later.

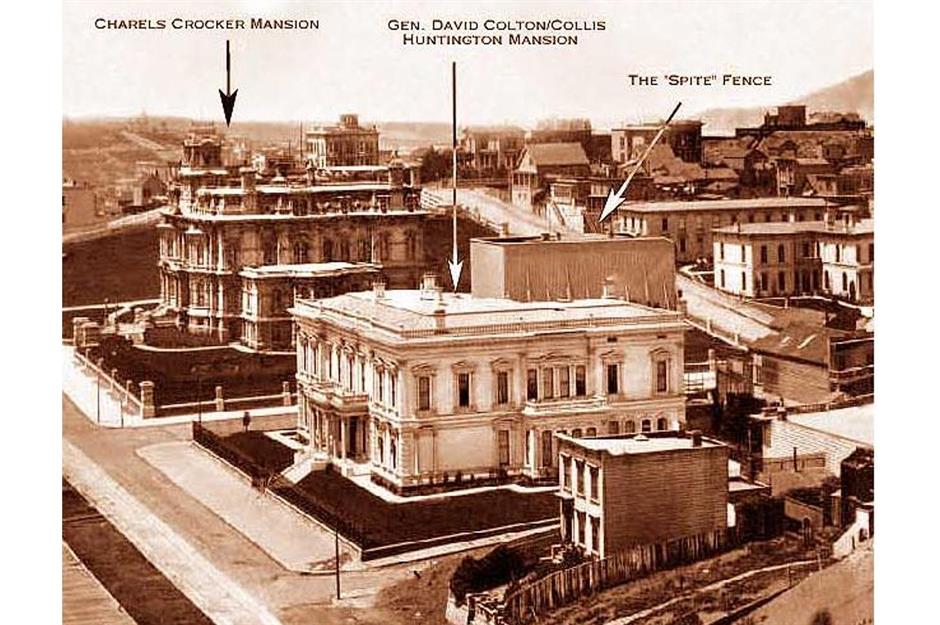

Charles Crocker Mansion, California

Charles Crocker’s Second Empire-Italian Villa-style mansion was intended to be a grand spectacle of his wealth and power, and included a 75-foot tower from which he could view the whole of San Francisco.

One of the 'Big Four' tycoons who founded the Central Pacific Railroad, Crocker built another mansion for his son William H. Crocker nearby. Both buildings were destroyed in the earthquake and fire of 1906.

Subsequently, the Crocker family donated the entire block as the site for Grace Cathedral, the cornerstone for which was laid in 1910.

Charles Crocker Mansion, California

More fascinating than his house was the so-called 'spite fence' that Crocker erected to upset his neighbour when he refused to sell.

Crocker made several offers to purchase the modest family home of undertaker Nicholas Yung, even doubling his original offer, but all to no avail.

Crocker built a 40-foot (12m) fence that deprived his neighbour of both sunshine and outlook, and became a symbol of capitalist power over 'the little man'. Yung eventually sold out to Crocker, but a few years later the great fire reduced much of the neighbourhood to cinders.

P.T. Barnum’s Waldemere, Connecticut

The inspiration behind the movie The Greatest Showman and celebrated for bringing entertainment to the masses, P.T. Barnum was also an inspired architect of his own homes.

The businessman built no fewer than four mansions in Bridgeport, Connecticut, throughout his life, including Waldemere, which means woods by the sea, that he built for his wife, Charity.

She didn’t enjoy the delights of the Victorian gingerbread-style house for long however, dying in 1873 while her husband was travelling in Europe.

P.T. Barnum’s Waldemere, Connecticut

When Barnum eventually returned home, he had a new, young wife, Nancy, in tow. Initially appreciative of Waldemere’s elaborate design, Barnum grew frustrated with its draughts and decided to build another home next door.

Pictured is the home's porte-cochère, a grand arch that allowed horse-drawn coaches to pull up outside the entrance.

Waldemere was demolished, and the couple moved into the new house, which they called Marina. Barnum passed away in the house in 1891, and Marina was eventually torn down in 1961 by the University of Bridgeport.

Stewart’s Castle, Washington, D.C.

A gold mining millionaire by the time he was 27, William Morris Stewart commissioned well-known Washington architect Adolf Cluss to build his city home on a plot of land on the north side of Dupont Circle.

Constructed in the Victorian Second Empire style, over five storeys, with a four-storey turreted tower and a cupola, the mansion covered 19,000 square feet (1,765 sqm) of living space. It was described by a local reporter on its completion in 1873 as surpassing “in magnificence anything to be seen in this city.”

Stewart’s Castle, Washington, D.C.

A fire destroyed the house in 1879, but it was restored after extensive renovation, and from 1886 to 1893, Stewart leased the house, fully furnished, to the Chinese Legation in Washington.

The interiors were lavish, with furnishings imported from Europe, and he employed an army of staff to run the house and the stables. However, the family hardly used it, and in 1899 it was sold to another millionaire who planned to build a neoclassical mansion that never materialised.

Instead, the house was torn down in 1901, and a bank was built in its place.

Thomas Carnegie’s Dungeness estate, Georgia

The younger brother of industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, Thomas Carnegie made his fortune in steel and co-founded the Edgar Thomason Steel Works.

In 1881, he purchased land on Cumberland Island in Georgia as a gift for his wife, Lucy, and their nine children, and commissioned a huge house. It was inspired by the turreted castles of his native Scotland.

The 59-room Dungeness had several pools, a golf course and 40 auxiliary buildings to house some 200 servants required to keep a mansion of this size operational.

Thomas Carnegie’s Dungeness estate, Georgia

After Carnegie’s death in 1886, his wife Lucy kept the mansion going until she died in 1916. But the family was forced to abandon the home following the financial crash of 1929.

In 1959, a mysterious fire which burned for three days destroyed the estate, leaving behind only the haunting ruins of what had once been a magnificent European-inspired mansion.

Cumberland Island has since been established as a national seashore and will be protected from commercial development.

Northfield Château, Massachusetts

Inspired by the Château de Chambord, the largest of all the châteaux in the Loire Valley, Northfield Château was completed in 1903 and was the summer residence of wealthy New York businessman Francis Robert Schell and his wife Mary.

Designed by Bruce Price, it mirrors the style of the architect’s most noted work, the iconic Château Frontenac in Quebec, and stood out as being rather showy in the midst of its small farming community setting in Massachusetts.

Northfield Chateau, Massachusetts

The 99-room fairytale castle included 36 bedrooms, 23 bathrooms and 22 fireplaces, like this one, as well as a private chapel. The 125-acre (50ha) estate featured landscaped gardens and a purpose-built lake for boating.

Mary refused to stay there following the death of her husband in 1928, and the property was sold to a school before falling into disrepair.

Prior to its demolition in 1963, much of its furniture was salvaged by the Tinney family and displayed at Belcourt Castle in Newport, Rhode Island.

Love this? Now discover the secrets of more historic homes

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature