Life in America’s secret atomic cities revealed in rare photos

America's Atomic cities

In the early 1940s, as the Second World War raged on, three US cities were built at record speed. They housed hundreds of thousands of inhabitants, offered schools, shopping malls, and churches, and were designed to play a vital role in the war effort.

But by 1946, they were gone. According to official maps, they never even existed.

Click or scroll to take a look back at America’s “atomic cities,” the three communities purpose-built to help build the bombs that ended the war...

The arms race is on

As the Second World War continued, the US entered a fierce arms race with Germany to be the first to develop atomic weapons. The US had been made aware of the Germans' potential capacity to build an “extremely powerful bomb” since 1939.

But it was not until America’s official entry into the conflict in 1941 that the Army Corps of Engineers established the Manhattan Engineer District to develop the technology for a counterattack.

Three testing sites

The undertaking, known as the Manhattan Project, was a top-secret government program involving three key nuclear development and testing facilities in locations across the country: Hanford, Washington; Los Alamos, New Mexico; and Oak Ridge, Tennessee.

These sites were carefully chosen based on a list of specific criteria required for testing, and were claimed by the government under the Second War Power Act of 1942, displacing farmers, homesteaders, and tribes of Native Americans in the process.

Sponsored Content

"The secret city"

Nuclear scientists theorised that there were two potential paths forward to building an atomic bomb, one through plutonium and the other through uranium, and sites were developed for each.

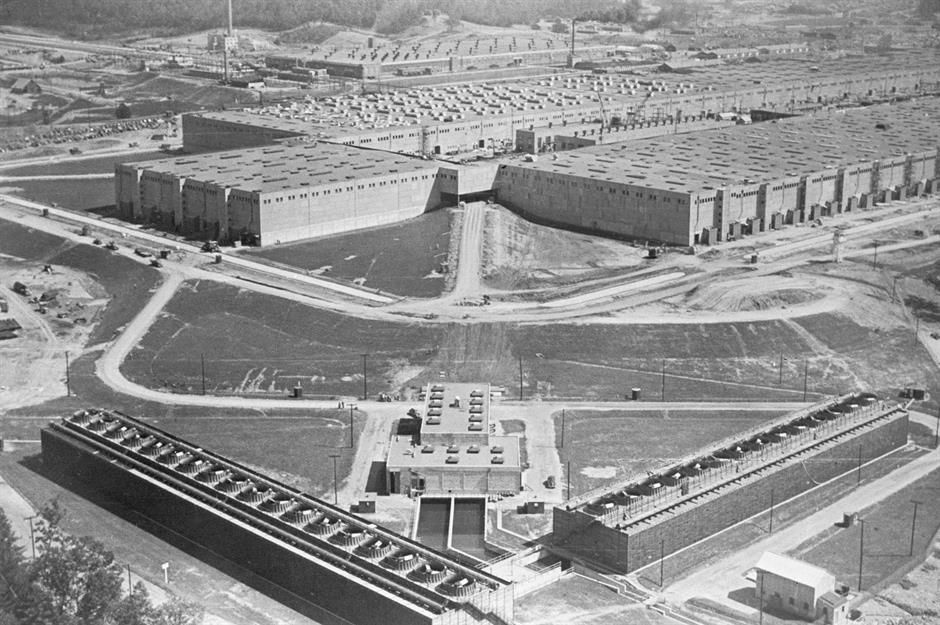

The Oak Ridge, Tennessee site was an enormous industrial complex designed to enrich uranium, which would ultimately serve as the headquarters of the nationwide project. Despite the fact that 100,000 workers were brought in to work there, Oak Ridge, known as “the secret city,” did not appear on any maps.

A rapid population influx

In its initial planning, Oak Ridge was expected to house roughly 13,000 people, who would be accommodated in a combination of prefabricated housing, trailers, and wood dormitories.

However, by the time Oak Ridge became the Manhattan Engineer District headquarters in the summer of 1943, its population was estimated to have risen to about 45,000, and by the end of the war in 1945, it was the fifth largest ‘city’ in the state of Tennessee, with a population of 75,000.

Alphabet houses

However, materials were in short supply, and housing was always outpaced by demand given the rapid influx of workers and their families. The original homes, known as “alphabet houses” because the limited number of designs were each assigned a different letter, were built of prefabricated panels of cement and asbestos or cemesto board.

“A” houses were small, consisting of just two bedrooms, while “C” houses might have a few more bedrooms, and “D” houses the luxury of a dining room.

Sponsored Content

Work at the production facilities

Located in a valley, a safe distance away from town, were the four production facility sites. The idea was to provide a level of containment for the various experiments in electromagnetics, plutonium, and gaseous and thermal diffusion taking place there, and to maintain a level of normalcy and security for the town’s inhabitants.

Residents at Oak Ridge lived a very insular life, largely shunned and mistrusted by the local Tennessee population.

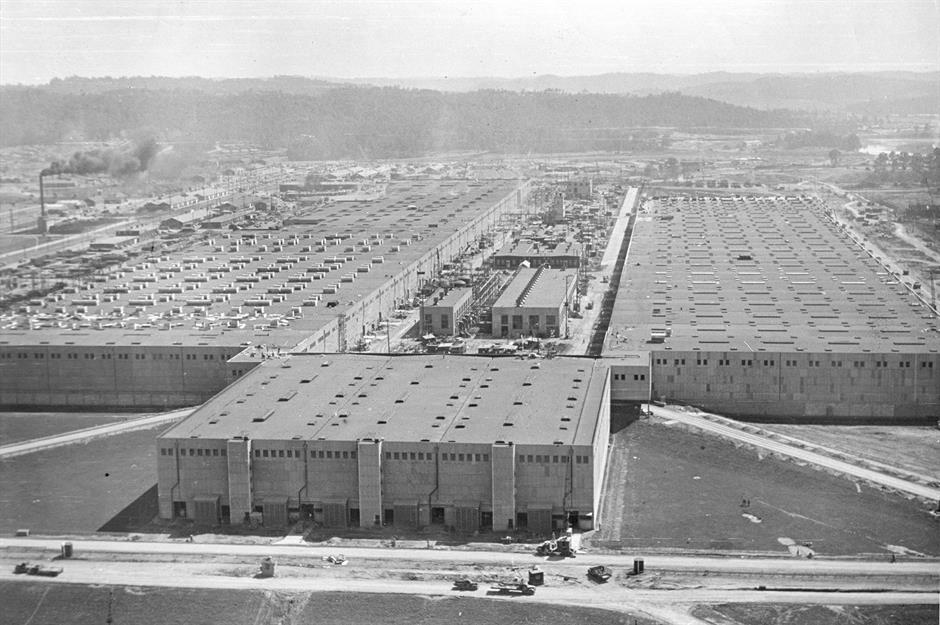

Inside the plants

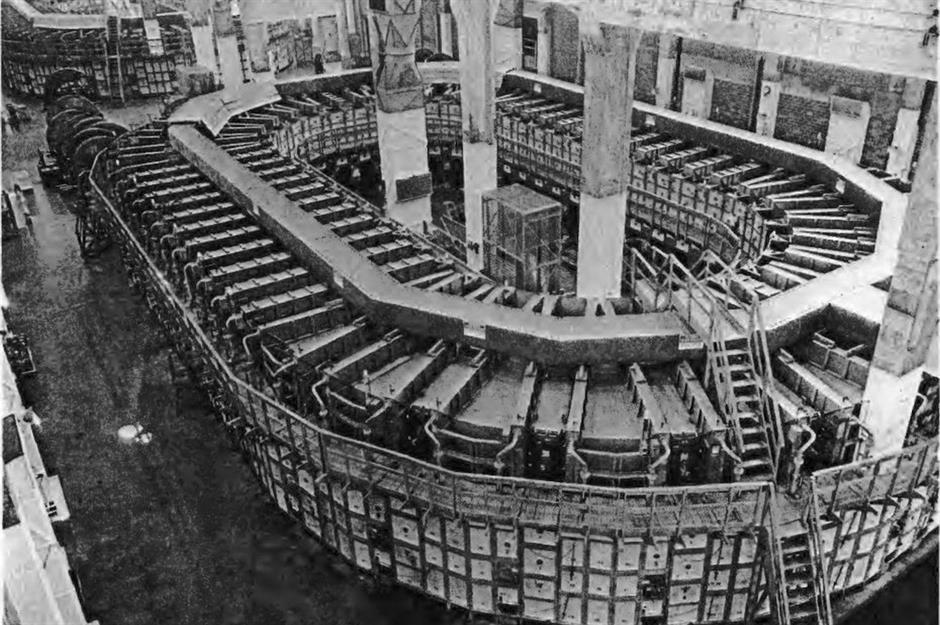

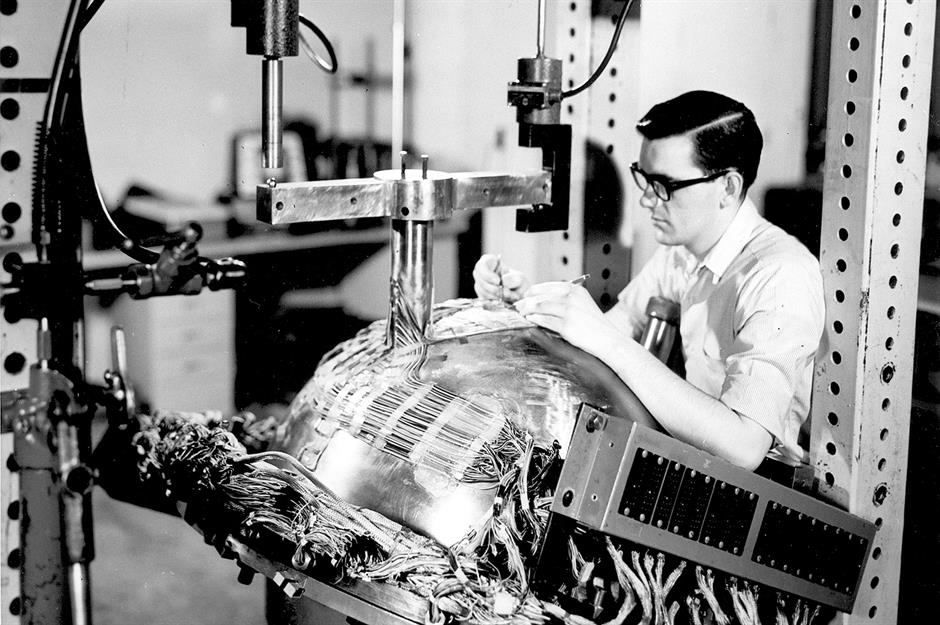

The most important technology under development at Oak Ridge was the X-10 Graphite Reactor, which was designed to prove that nuclear chain reactions could be controlled. It was the first step towards proving that the power of the atom could be harnessed for a bomb.

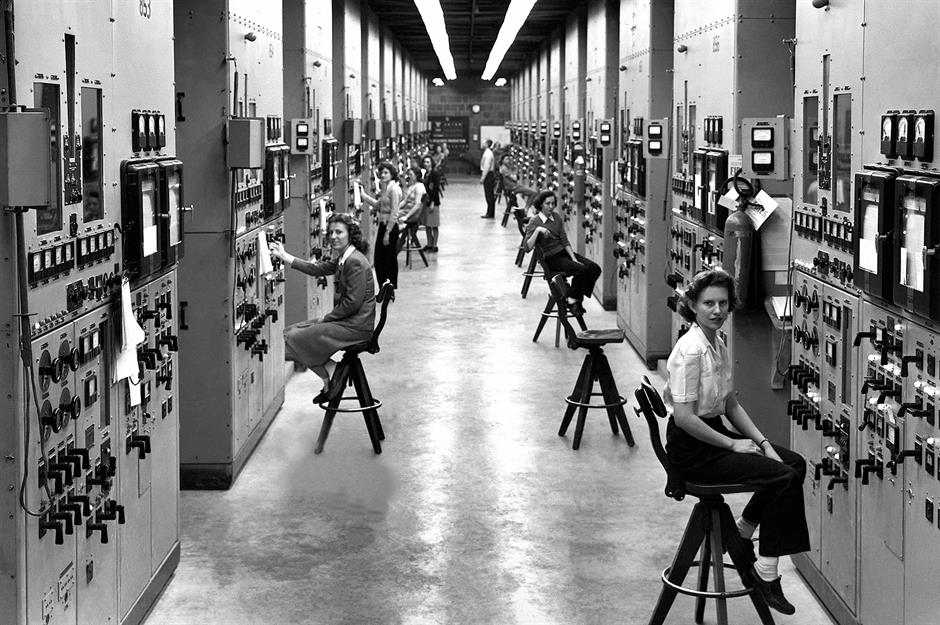

Over at the Y-12 plant, pictured here, was primarily concerned with the production of fissile material, another important ingredient for bomb construction.

Generous compensations

Meanwhile, the families of the government workers and scientists kept house, went to school, and visited the open-air, ultra-modern shopping centre, pictured here, which had been custom-built for Oak Ridge’s atomic city.

Unlike the rest of the country, which was suffering from the derivations of wartime rationing, Oak Ridgers had been compensated for their willingness to uproot their lives with unlimited ration stamps and cash payouts.

Sponsored Content

Hanford, Washington

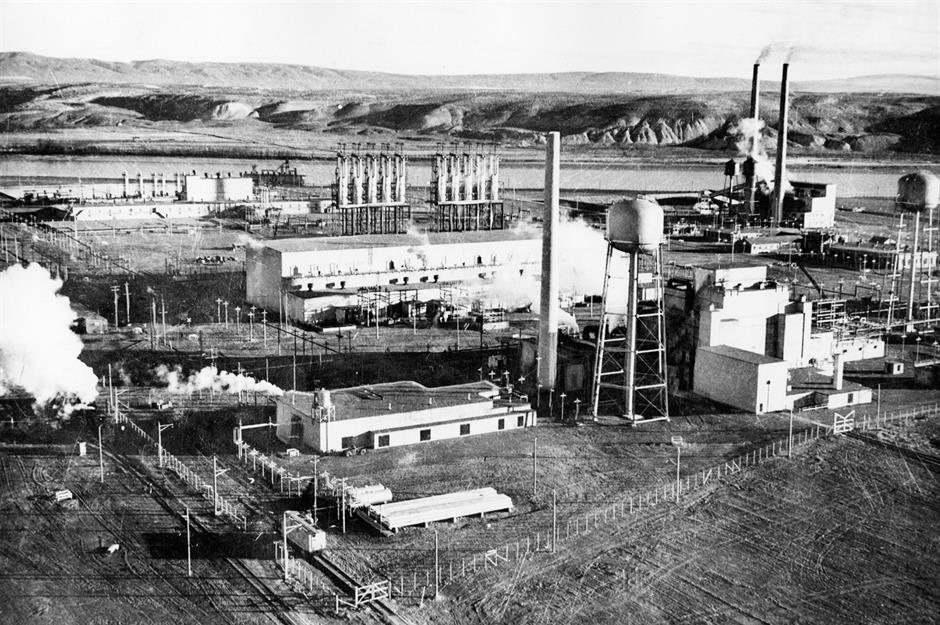

The next atomic city was Hanford, Washington, which was predominantly responsible for the industrial-scale production of plutonium using nuclear reactors.

The Army Corps of Engineers built three nuclear reactors along the Columbia River, each the size of a small city, and hired nearly 100,000 workers to man the facilities between 1943 and 1945.

At its peak in 1944, the Hanford Construction Camp was home to nearly 50,000 workers.

Hastily built homes

While single men lived in barracks or encampments, temporary huts known as hutments, a wide variety of housing options were scraped together to accommodate families.

These included the homes of the original residents of the area who had been forced to relocate, as well as trailer units and prefabricated houses like the one pictured here.

These homes were of a simple one or two-room construction and were designed to be assembled as quickly as possible.

Home life for women

The majority of facility employees were men, with women making up just 10% of the workforce, employed predominantly in clerical, foodservice or domestic work positions.

However, women played important unofficial roles in Hanford as well, raising families, getting involved in churches, facilitating children’s activities like the Boy and Girl Scouts, and even providing entertainment like music and dancing.

They also taught in the schools, like the one pictured here.

Sponsored Content

Large-scale labour

Certain domestic chores for the plant had to be tackled en masse, or family style. Meals were prepared by an army of cooks and served in an enormous mess hall, where employees gathered at large tables set for 12, in a fashion which reminded some of a prison camp.

This image of laundry being done in bulk also looks like it might have been taken in a prison, but it was in fact standard procedure to remove any toxic chemicals from workers’ clothes.

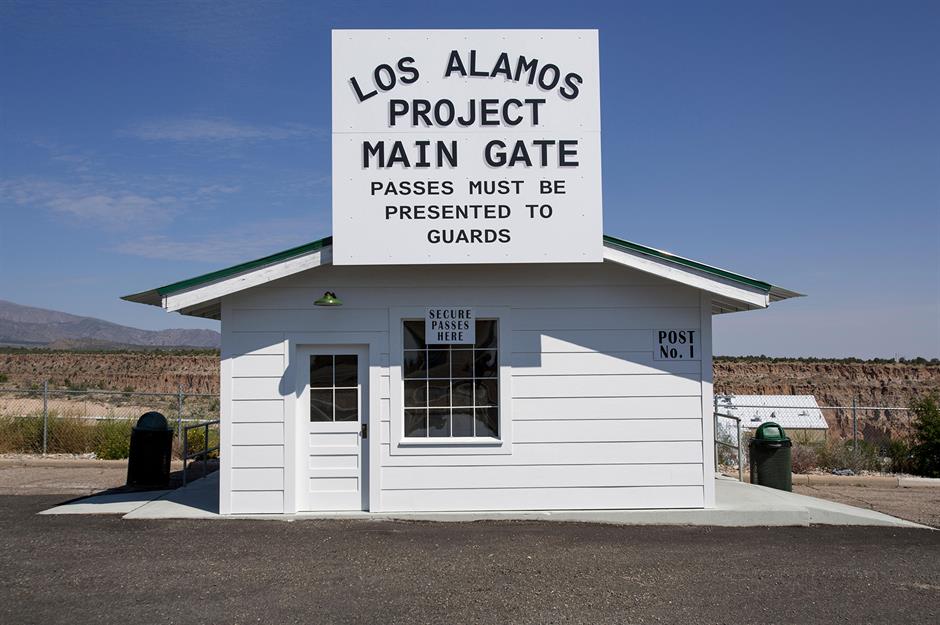

Los Alamos, New Mexico

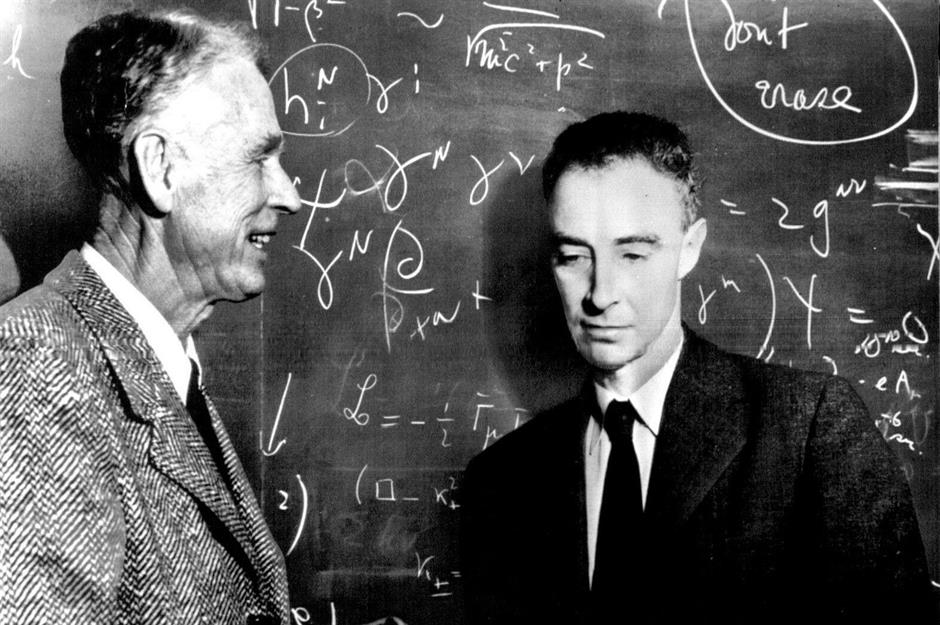

Perhaps the most famous of the three sites, Los Alamos was the heart of the actual construction of the atomic bomb, where the enriched uranium from Oak Ridge and plutonium from Hanford were combined for the first theoretical and experimental tests.

The home of J. Robert Oppenheimer himself, Los Alamos provided top-level secrecy during the designing and construction of The Gadget, the world’s first atomic device, and atomic bombs Little Boy and Fat Man.

A self-contained city

However, like Oak Ridge and Hanford, Los Alamos was also home to a thriving community…whose inhabitants were forbidden to talk about.

To keep the secret city, well, secret, Los Alamos was designed to be entirely self-contained, with schools, hospitals, and even theatres which pulled double duty as dance halls on Saturdays and churches on Sundays.

Pictured here, physicist Dr Otto Frisch plays the piano at KRS, the Los Alamos community radio station.

Sponsored Content

Dormitory housing

Referred to as an “instant city,” Los Alamos was built almost entirely overnight, which meant that its construction was somewhat shoddy and only ever designed to be temporary.

Los Alamos offered housing in single-sex dormitories like the ones pictured here for its single staff members. Compared by historians to a “university town that was controlled by the military,” the town hired architect Willard C. Kruger to build four such dormitories, two for men and two for women.

"Bathtub Row"

However, Los Alamos was also home to some of the highest-ranking members of the Manhattan Project, who benefitted from comparatively luxurious, well-built homes. Admittedly, the luxury standards were a bit different from what one might expect.

In the hastily built Los Alamos housing, bathtubs were a rarity, and homes with these facilities were reserved for senior officials and engineers, earning the better-built section of the city the nickname “bathtub row.”

A social caste system

The initial population at Los Alamos was extremely homogeneous, consisting mainly of highly educated male scientists in their 20s and 30s and their families, all from healthy, middle-class backgrounds.

By the end of the war, Los Alamos' population had reached 6,000, and while the inhabitants had diversified slightly, they were still dominated by an overarching caste system, with scientists and their families at the top, followed by administrators and Army officers, then other civilians and finally enlisted men and women.

Sponsored Content

Work hard, play hard

Los Alamos cultivated a culture dominated by work, which meant that this caste system dictated not only housing, but dining and recreational activities as well. Official hours for laboratory work were eight hours a day, six days a week, with strict time slots for meals in the canteen.

However, employees learned to make the most of their rare off-work hours, getting involved in amateur dramatics and concerts, attending movies and dances, throwing parties, and making the most of the outdoors.

The first explosion

Los Alamos was also the site of the first nuclear explosion. In July of 1945, the plutonium implosion device known as The Gadget was detonated in a test run at a site located 210 miles south of the city.

Code-named “Trinity,” the test explosion vaporised the tower from which The Gadget had been suspended, and sent a blast of heat tearing across the surrounding desert, knocking bystanders to the ground, and turning asphalt and sand into green glass.

The Atomic Age

The Trinity detonation was deemed a success, with tremendous implications which would forever change the course of history. It meant that the atomic bombs were ready to be used by the US military, which they were on August 6, 1945, when the US dropped them over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ending the war.

However, it also emerged in the atomic age, which would last throughout the 1950s and 60s as the US entered the Cold War.

Sponsored Content

Secret cities no more

With the end of the Second World War came the question of what would become of the “secret cities,” secret no more. “Now They Can be Told Aloud These Stoories [sic] of the Hill” ran the headline of a rushed edition of the Santa Fe New Mexican.

Below ran a story which revealed that the mysterious settlement on a nearby mesa, referred to by locals as ‘the hill’, had secretly been designing the government’s latest weapons of mass destruction.

An atomic future

Policymakers anticipated that the Manhattan Project’s infrastructure would be handed over to a civilian commission, harnessing the nuclear fission technology perfected by the Project for the development of other technologies.

While the former secret cities were substantially depopulated and no longer residential, their plants remained in operation as important research facilities for further developing nuclear technologies for purposes including medical imaging systems and radiation therapies.

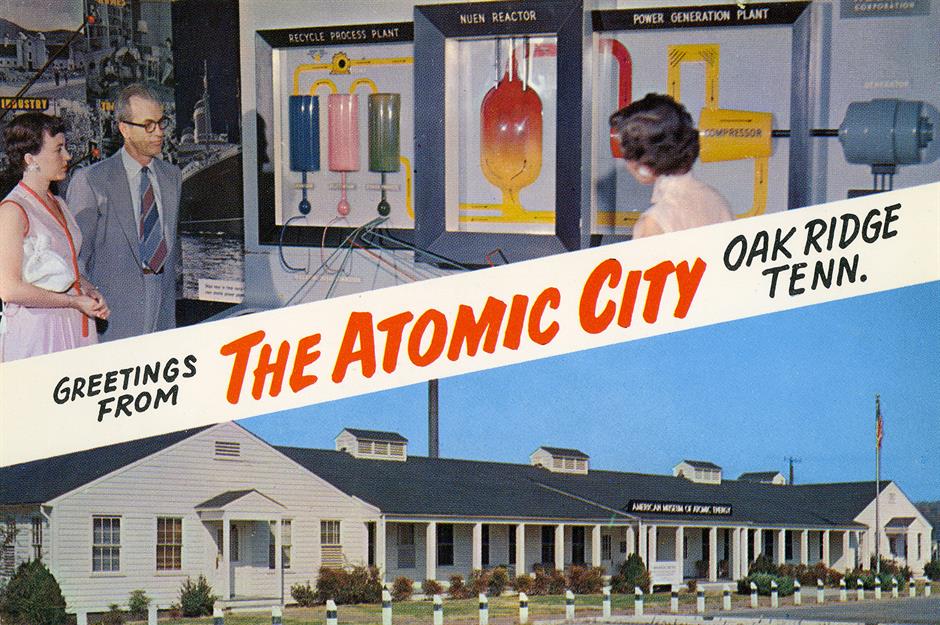

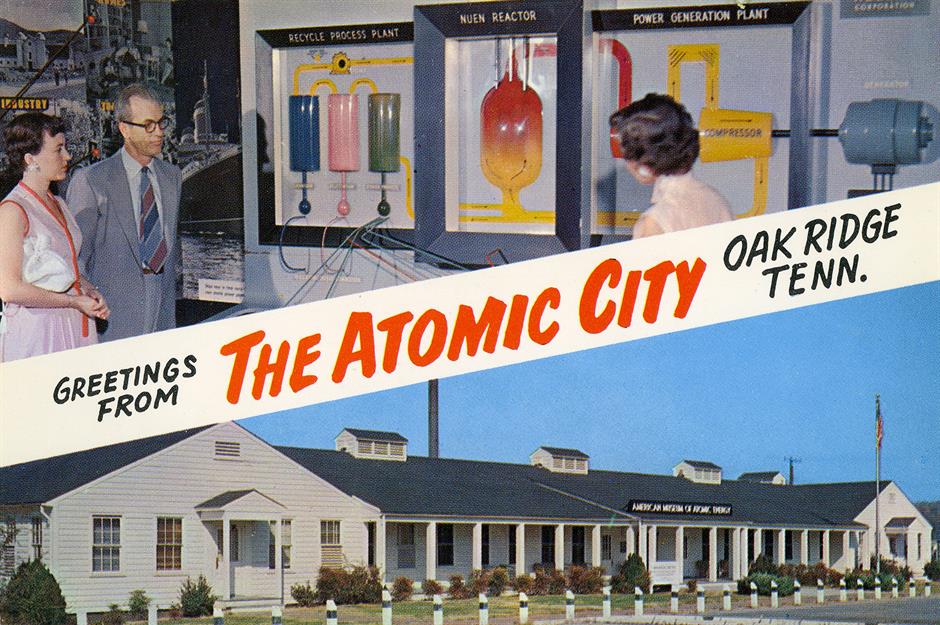

Visit the atomic cities

Today, the locations of the three cities are part of the Manhattan Project National Historical Park, operated by the National Park Service, and are three thriving communities in their own right.

Visitors can explore museums which commemorate the complex technological and ethical issues raised by the development of the atomic bombs, which are still being developed, analysed, and debated today.

Loved this? Now discover more incredible homes throughout history

Sponsored Content

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature