Shadow Brook: the tragic tale of America’s second-largest Gilded Age mansion

The rise and fall of a legendary estate

Created for entrepreneur and banker Anson Phelps Stokes in 1893, Shadow Brook was once the second-largest private residence in the United States after Biltmore.

Just two miles (3.2km) west of Lenox in The Berkshires in Massachusetts, the sprawling Tudor-Revival mansion had a frontage measuring more than 400 feet (122m) and boasted 100 rooms. Tragedy struck in 1956 when the house was lost to a devastating fire, but its legend lives on in a series of rare archive photographs.

Click or scroll on to tour the splendid property and discover its fascinating history…

The end of Shadow Brook

As the following images from the Lenox Library Association show, the home was impressive.

But despite its size and spectacular location, halfway up Bald Head Mountain overlooking Stockbridge Bowl, also known as Lake Mahkeenac, the estate was never occupied by any one family for longer than seven years. This led to local superstitions that the original American Indian inhabitants had cursed the land.

Stokes was one of several Gilded Age figures, including Margaret Emerson Vanderbilt and Andrew Carnegie, who made Shadow Brook their summer home and contributed to its reputation as one of the most lavish properties in America. Let's hear their story...

Who built Shadow Brook?

Anson Phelps Stokes and his wife, Helen Louisa, were one of the wealthiest couples in America when they set about creating Shadow Brook in 1891.

The grandson of Anson Green Phelps, one of the largest traders of tin plate in the world, Stokes had invested his money in real estate and mining. He was said to be worth around $25 million – or $812 million (£598m) in today’s money – at the time of his death in 1913. His wife, Helen, was her father’s sole heir, inheriting a million-dollar fortune and a house on Madison Avenue.

Mammoth proportions

In 1889, they purchased The Homestead at Lenox and started buying up land in the now gentrified Berkshire Hills.

Within a couple of years, feeling they had outgrown the original 40-room country house, they commissioned the fashionable architect of the time, McKim, Mead & White, to design the sprawling three-storey house, which was topped with distinctive deep brown tiles and 12 chimneys.

Mrs Stokes later fell out with the design team, replacing them with little-known local architect H. Neill Wilson.

Glorious grounds

For the gardens of the 900-acre (364ha) estate, the couple engaged the services of Frederick Law Olmsted, who had designed New York City’s Central Park, and who incorporated stables, tennis courts, heated greenhouses, and even a field dedicated solely for croquet.

He may well have fallen out with Mrs Stokes too, as he was later replaced by Ernest W. Bowditch to finish the job.

A grand foyer

The Tudor Revival-style mansion boasted 17 reception rooms on the ground floor alone, including the ballroom, library, study, breakfast room, and music room.

Just beyond the elaborate porte cochère, where guests would arrive in their carriages or cars, the foyer featured timbered ceilings set with ornate plasterwork beneath which there was a welcoming hearth and heavy carved furniture.

The Pompeian Hall

The Pompeian Hall, as it was called, was clad in painted panels, both on the walls and the ceilings, with figures of humans and horses carved into the frieze surrounding the room in its entirety.

The family used the room to house the many treasures they had acquired during their trips abroad, including a tiger skin rug and potted exotic plants paired with fine Chinese porcelains.

The Morning Room

The morning room was a breath of fresh air, with white walls and panelled ceilings as well as intricate fretwork dividing one corner of the room from a tower.

Traditionally a light-filled room where the lady of the house would prepare for the day ahead, the furniture was upholstered in floral textiles, while the walls featured wainscoting and silk wallpaper draped with plaster garlands.

Relaxing in the parlour

The focal point of the parlour was the Gothic fireplace with its huge surround embellished with intricate relief work. The fluted ionic columns on either side served not just as decoration, but also as much-needed support for the substantial coffered ceilings.

In true Victorian style, the room was decorated in an explosion of mismatched textiles, wall coverings, and rugs, as seen here.

Spacious dining room

The house had three dining rooms, the largest of which is pictured here. The exposed ceiling beams were supported by large corbels or supports, evenly spaced to line up with the pattern of the wallpaper. Underneath, were half-height board and batten wall panels creating a distinctive textured effect.

To give you some idea of the size of the room, the rug was said to measure 30 feet (9m) by 48 feet (15m), so guests certainly had room to spread out.

Beautiful ballroom

No house of this magnitude would be complete without a ballroom, and this one, with its spectacular ceiling, is a beauty. You can almost imagine twirling around its polished floor, looking up at the dizzying geometry of its ceiling and wood panels, carved by master woodworkers.

The Stokes family loved to entertain and were known for their lavish parties to celebrate Christmas and New Year.

Bedrooms for all the family

The second floor was reserved for guests, with over 20 guest suites, and the third floor, featuring another elaborate ceiling, was set aside for the family, with 11 master bedrooms and nine bathrooms.

The bedrooms were notable for having private bathrooms, something which was rare for the period, regardless of social class.

Impressive staircase

There were a further 11 bedrooms for live-in staff and five servants’ bathrooms, as well as the usual store rooms, linen and laundry rooms, and wine cellars which were located in the basement.

Like most grand houses of the time, the different levels were accessed via an equally impressive staircase, complete with ornately carved railings and bannisters. The family certainly kept the local master wood carvers busy!

House parties

Once the house was completed, Stokes spent the next six years hosting the friends of his fairly grown-up children, holding weekend parties for sometimes 50 guests at a time.

As well as their regular festive parties, they invited friends from New York to join them for winter sports in the mountains, which included tobogganing, sleigh-riding, snow-shoeing, and ice-fishing.

Tragedy strikes

The fun and games came to something of an abrupt end in the summer of 1899, when Stokes was thrown from his horse. His leg was so badly damaged that it had to be amputated soon after.

With Stokes no longer being able to enjoy playing golf and riding horses in the surrounding countryside, the couple decided to rent out the house and move back to New York City.

Mrs Maggie Vanderbilt

After being leased out for a few years as a hotel, Shadow Brook was sold to Canadian businessman Spencer Proudfoot Shotter in 1906 for a reported $250,000, equivalent to nearly $9 million (£6.6m) today. He was tried for violating anti-trust laws, and although he won the case, the legal fees cost him his fortune.

In desperate need of money, he leased the estate for $15,000 a month, equivalent to around $530,000 (£394k) today, to Mrs Maggie Vanderbilt, whose husband, Freddie Vanderbilt, had recently lost his life when the cruise liner he was on, RMS Lusitania, was torpedoed by the Germans in 1915.

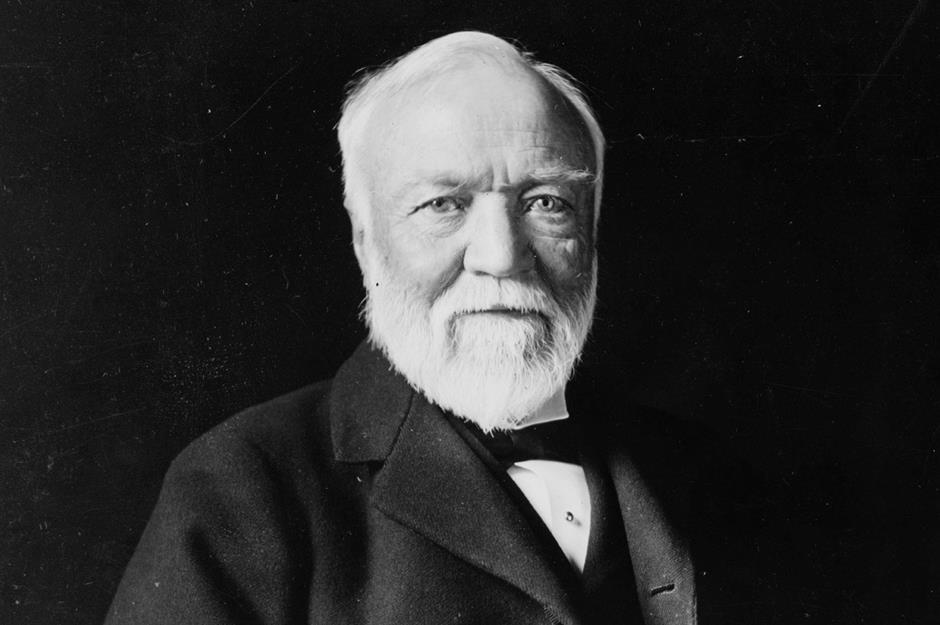

Andrew Carnegie

Shadow Brook’s next high-profile resident was steel magnate and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie, who had heard about the estate when he was renting the Brick House in Connecticut, the country house of Anson Phelps Stokes’ widow, Helen Louisa.

Unable to travel to his beloved Skibo Castle in Scotland due to his failing health and the war in Europe, he paid $350,000, equivalent to $10.3 million (£7.7m) today, to Shotter’s creditors in 1916.

Carnegie made some changes to the house, including the instalment of an indoor fire safety sprinkler system, and proclaimed it was “as dear to him as was Skibo Castle”. Sadly, he didn’t enjoy it for long and passed away here in August 1919.

Consumed by flames

The estate was sold for about $200,000, equivalent to around $3.8 million (£2.8m) today, to the Jesuits of the Province of New England in 1922 and converted into a seminary.

It was still being run as such when an oil explosion, which started in the boiler room, sparked a fire that tore through the house on 9 March 1956, taking the lives of three priests and a lay brother.

Tragically, they were unaware of the sprinkler system that Carnegie had installed years previously, and the storied mansion was consumed by flames.

Reduced to ruins

Little remained of what was once one of the most incredible mansions in America. This haunting photograph from The Berkshire Eagle newspaper looks like the ancient ruins of a medieval castle.

The destruction was so complete that rebuilding was deemed impossible, leading to the decision to construct a new building on another site further down the hill.

The Kripalu Centre for Yoga and Health

The new building bore no architectural resemblance to its predecessor. Critics described it as “a monumental mediocrity”.

The fireproof structure, which was also known as Shadow Brook, opened in 1958 and served as a seminary until 1970, when the brotherhood moved to Boston. The building sat empty until 1983, when it was sold and became The Kripalu Centre for Yoga and Health.

Spectacular location

The fire marked the end of Shadow Brook as a physical structure, but its history, riddled with bad luck, short-term ownership, and ultimate destruction, left some wondering if its demise was simply a result of misfortune or whether something more mysterious had been at work.

Alas, we shall never know!

Loved this? Now discover more incredible homes from history

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature