Incredible old photos of home life in Alaska 100+ years ago

Here's what life in Alaska looked like before it became a US state

A century ago, life in Alaska was a rugged blend of endurance, isolation, and quiet beauty. Long before paved roads, supermarkets, and the internet reached the Last Frontier, families carved out lives in one of the most remote corners of the world.

From the early shelters of Native Alaskans to the humble lodgings of gold miners and the beginnings of suburbia, these remarkable old photographs reveal the realities of home life before Alaska became a US state.

Click or scroll on to discover how Alaskans lived 100 years ago...

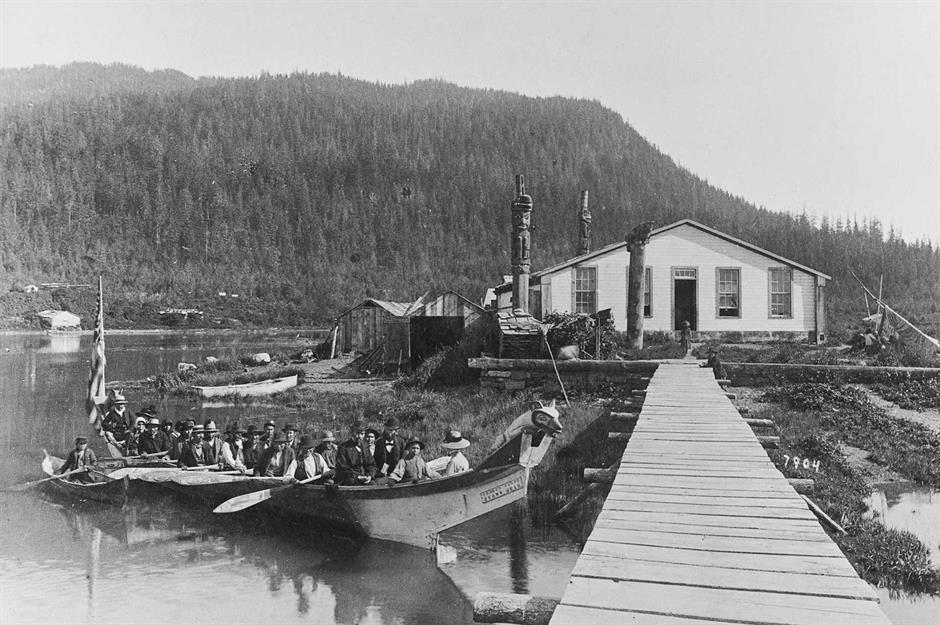

1890: a Tlingit clan house

Pictured here in 1890 is a Tlingit canoe arriving at the Chief Shakes tribal house on Wrangell Island in the Alaska panhandle. The Tlingit are Native Alaskans who have called southern Alaska home for at least 10,000 years.

The canoe carries a funeral party and, notably, it's flying an American flag. While the US purchased Alaska in 1867 for $7.2 million (more than $157 million (£117m) in today's money), it wasn't the first nation to settle the remote region.

The Russian Empire colonised Alaska from the mid-17th century and established settlements along its coastline.

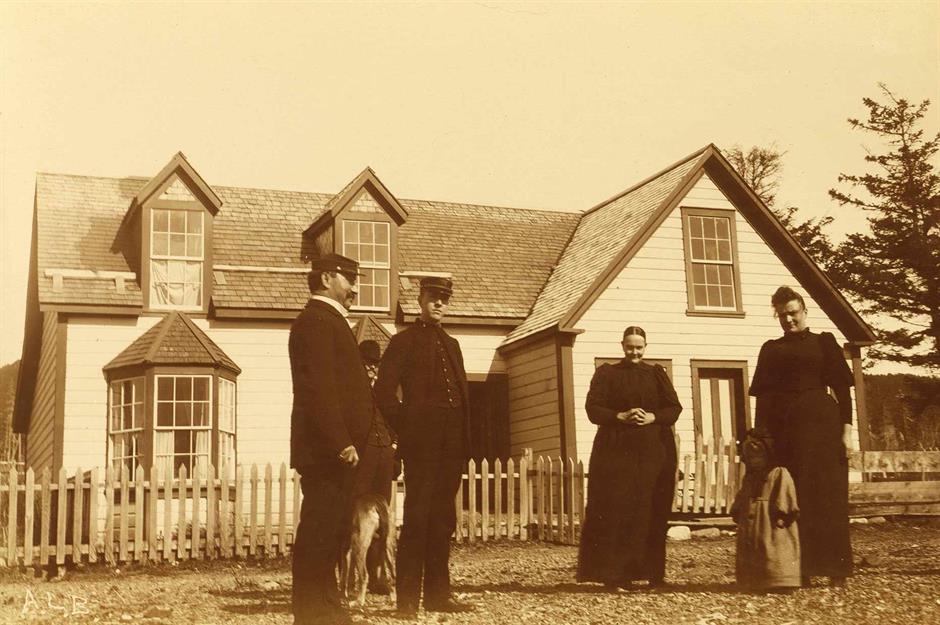

1895: a sailor's clapboard home

In this image taken sometime between 1894 and 1895, three men, two women, a child, and a dog stand in front of a traditional clapboard house. From the men's uniform, they're assumed to be sailors.

Following America's purchase of Alaska from Russia, shipping was the outpost's only link to the US mainland, and sailors would navigate the challenging waters to transport cargo to the Last Frontier.

American ships had also been engaging in commercial whaling, a practice that's now banned, decades before the Alaska purchase, leading some sailors to take up residence in the territory.

Sponsored Content

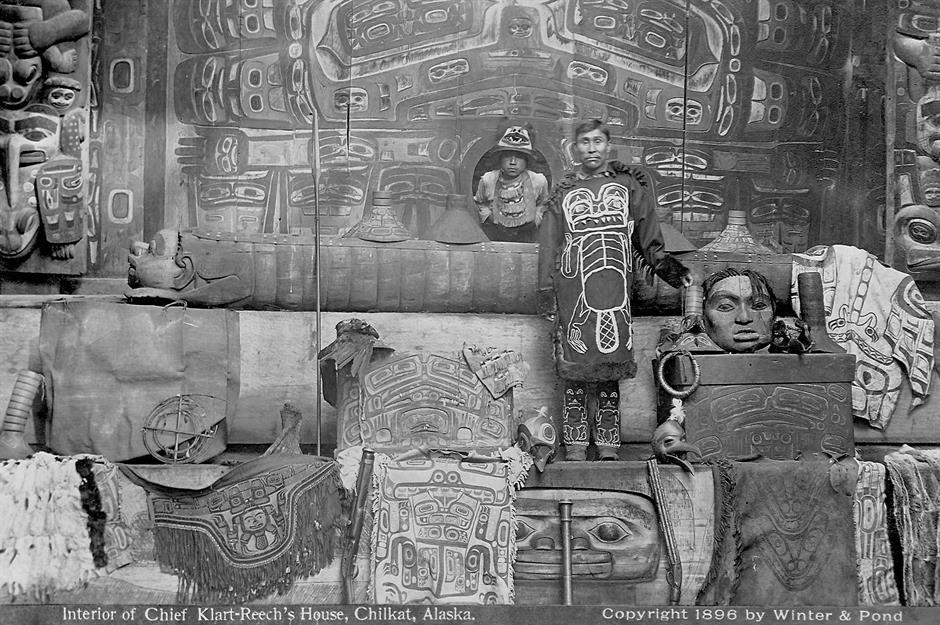

1895: the elaborate interior of a Whale House

This remarkable photograph from 1895 captures the elaborate interior of the Whale House of the Gaanextiedi clan, a lineage of the Tlingit peoples. The ceremonial house was located in Klukwan, an ancient village on the banks of the Chilkat River.

Known for its breathtaking carvings, thought to be the work of Kadjisdu.axtc (pronounced Kad-jis-too-ach), the craftsmanship has been compared to the Sistine Chapel.

Since 2016, four carved posts and the intricate rain screen from the original structure have been on display in a replica clan house at the Jilkaat Kwaan Heritage Center in Klukwan.

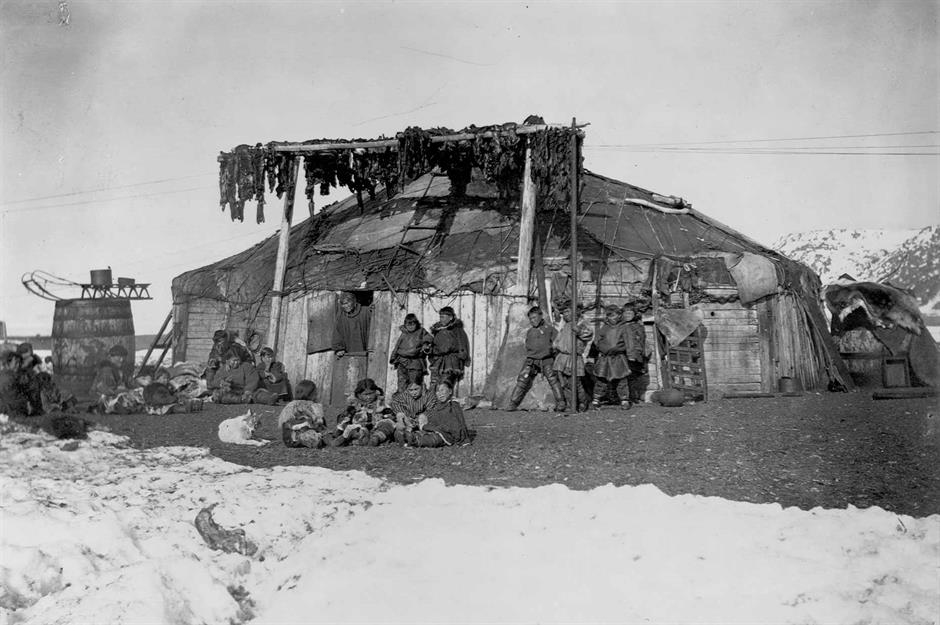

1898: a traditional winter house

Along with the Tlingit peoples, other Indigenous communities in Alaska include the Aleuts, the Inuit, and the Haida, along with other First Nations tribes. Living off the land is a central philosophy for Alaska Native communities, who have historically relied on hunting, fishing, and foraging.

This image taken in 1898 depicts a traditional winter house crafted out of driftwood and animal skins by a Native Alaskan family. The design is strikingly similar to constructions found in Siberia during this period. In the last Ice Age, the Russian province was connected to Alaska via an ancient land bridge and there are some shared cultural elements between the two regions' Indigenous groups.

1899: a chief's house flanked by a totem pole

Pictured here is a chief's house in the abandoned Tlingit village of Cape Fox. This photo was taken in 1899 by members of the Harriman Alaska Expedition, who had embarked on a two-month survey of the coastline. The prominent totem pole, thought to depict a series of bears, is exquisite in design. These immense carvings typically reference kinship, events, and shared histories.

17 years after the US purchased Alaska, the Organic Act of 1884 was passed, establishing a government, though one that excluded Native Alaskans. While the legislation did not resolve land claims, it did state that Indigenous peoples "shall not be disturbed in the possession of any lands actually in their use or occupation". However, Congress reserved the right to define how land titles might be acquired in the future.

Sponsored Content

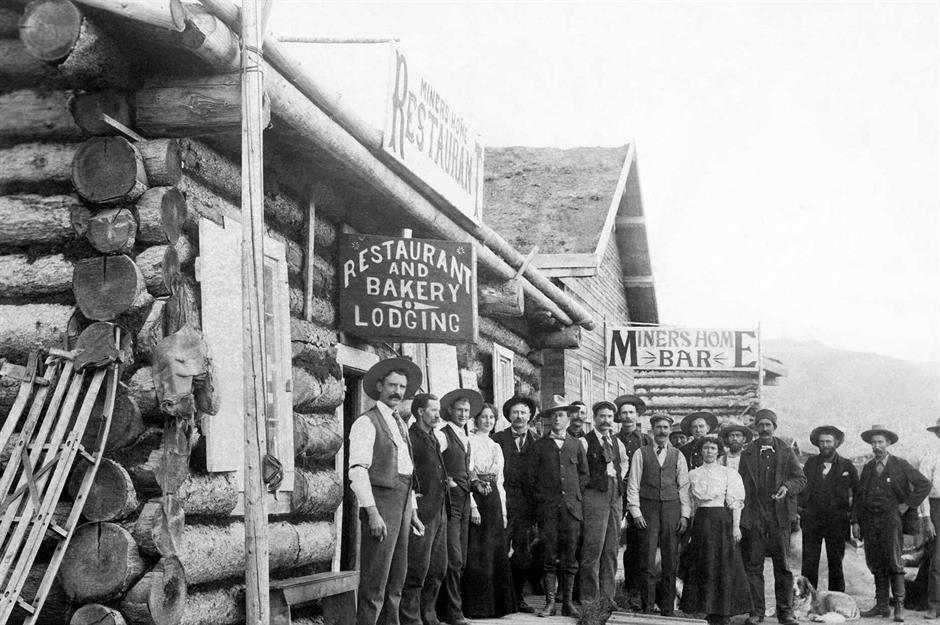

Late 1890s: a gold rush mining town

Alaska's non-Indigenous population ballooned after gold was discovered in the Pacific Northwest in 1896. Thousands of people journeyed to Canada's Klondike region, but by 1898, swathes of prospectors turned their sights to neighbouring Alaska and began scouring its wilderness.

Over 50 gold-mining camps were established across Alaska to accommodate the needs of these new arrivals, some of which solidified into towns.

Pictured here in the late 1890s is the community of Bettles, founded as a trading post. Miners could obtain lodgings and food in this humble log building.

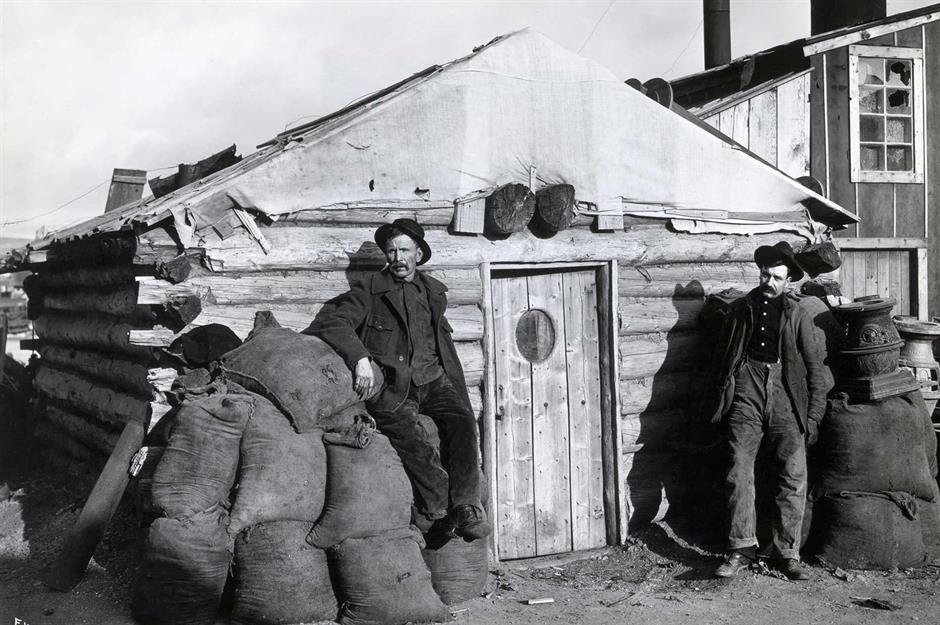

1900s: the first log cabin in Nome

In 1898, prospectors struck gold in Nome, situated on the southern shore of the Seward Peninsula. Four years later, gold was also found in the hills of Fairbanks in Alaska's east-central interior.

This photograph from 1900 reportedly shows the first log cabin built in Nome. The modest construction is flanked by two miners, who perhaps called it home for a time.

By the turn of the century, Nome had rapidly grown from an outpost to a fully fledged city, complete with stores, restaurants, saloons, and a road system.

1904: middle-class lodgings in Nome

It wasn't just the working class that was lured to Nome by the promise of wealth. Middle-class businessmen also saw the gold rush as a lucrative opportunity.

But rather than panning for gold, these savvy entrepreneurs saw that there was money to be made from selling goods and services to the burgeoning miner population.

A stately gentleman is pictured here in his lodgings in Nome in 1904. While his identity is unknown, the trappings of his bedroom suggest his middle-class status, from the oil lamp on the table and the ornately framed painting on the wall to the lace drapings and cornice frieze.

Sponsored Content

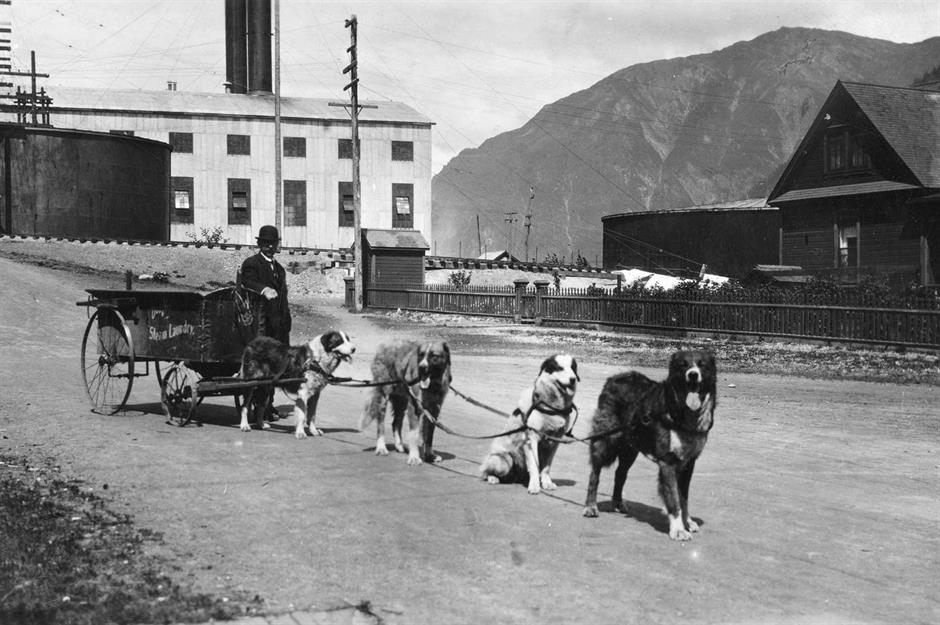

Early 1900s: a dog wagon delivering laundry

This photograph, taken in the early 1900s, shows a team of four dogs hitched up to a laundry wagon to help distribute laundered bundles around a town near Linkum Creek on the Kenai Peninsula, another gold rush hotspot.

It seems as though the newcomers in this mining outpost took a leaf out of the book of Native Alaskans. The area's Indigenous people have used dogs for transportation for thousands of years, from pulling meat and animal skins to camping equipment on toboggans and sledges.

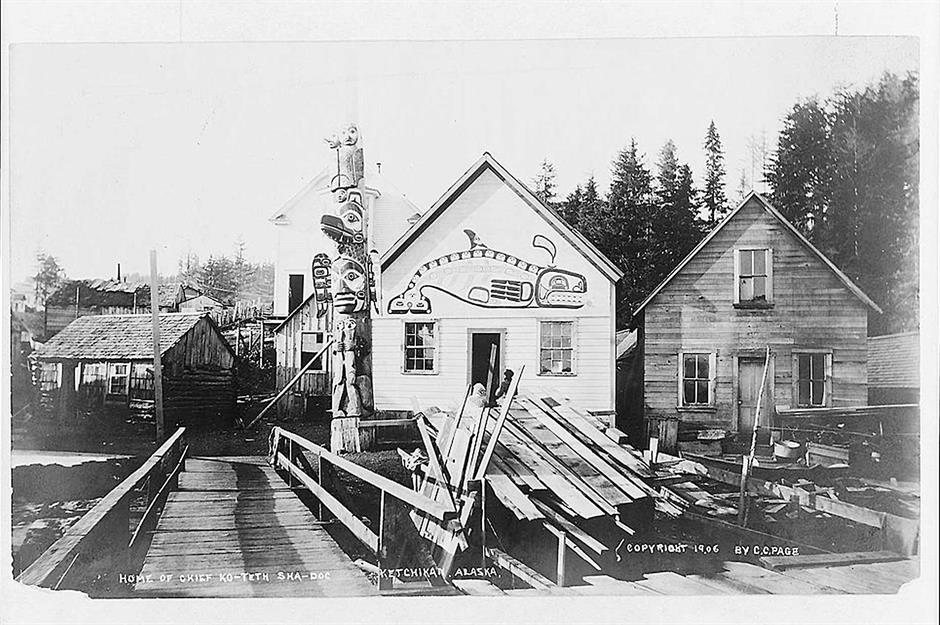

1906: the home of Chief Ko-Teth Sha-Doc

This remarkable clapboard house, emblazoned with a killer whale motif and flanked by a totem pole, was the home of Chief Ko-Teth Sha-Doc, a local Native Alaskan leader. The property was photographed in 1906 in Ketchikan, a city perched on Alaska's Inside Passage.

Ketchikan Creek, where this home appears to be, was an area that was fished in by Indigenous peoples for centuries. However, in 1887, settlers from Oregon constructed a salmon cannery by the water, before buying up the land.

Ketchikan was developed further during the gold rush, with gold, silver, and copper mines established in the region.

1907: the company town of Douglas

Pictured here is the bustling mining town of Douglas Island in 1907, just across the water from the then newly incorporated city of Juneau.

Gold was discovered on the island in 1881 by Pierre Joseph Erussard, who sold the claim to John Treadwell, a Canadian prospector. Over the following years, Douglas Island was transformed into a mining hub – four years after this photograph was taken, it was considered the world's largest operating hard rock gold mine.

To support the island's workforce, homes were built for the miners and their families, along with a store, butcher's shop, school, and leisure facilities.

Sponsored Content

1909: the governors' mansion in Juneau

In 1906, Juneau was made the territorial capital of Alaska, an honour that had previously been awarded to nearby Sitka during the Russian occupation. A logical choice for the seat of government, Juneau had a prosperous mining industry and, crucially, it was a mere steamship journey away from Seattle.

This was one of Juneau's first governors' mansions, captured in 1909. The Victorian-style building featured a turret, clapboarding, and intricate woodwork.

But just a year later, Congress would authorise $40,000 for the construction of a new executive mansion designed by John Knox Taylor (just under $1.4 million (£1m) when adjusted for today's inflation).

1910: the refined interior of a company house

Pictured here in 1910 is the refined interior of a company house run by the North American Commercial Company, which leased Alaska's Pribilof Islands from 1890.

The islands in the Bering Sea were used as a base for harvesting seal furs until the 1910 Fur Seal Act put an end to the operation.

The islands are home to the Indigenous Aleut peoples, and during both periods of Russian and American ownership, they were poorly treated and their culture and traditions suppressed.

1912: an Aleut sod hut

In a bid to force the Aleut to assimilate, their Indigenous sod huts were destroyed and replaced with American-style wooden homes, which were deemed 'healthier'.

This is a traditional Aleut house in Akutan, another island in the Bering Sea, pictured in 1912. The structure consists of a frame made from wood or whale ribs, which was clad in sod and grass.

A pole ladder provided an entrance through the roof, and the communal living space featured sleeping areas around its perimeter.

Sponsored Content

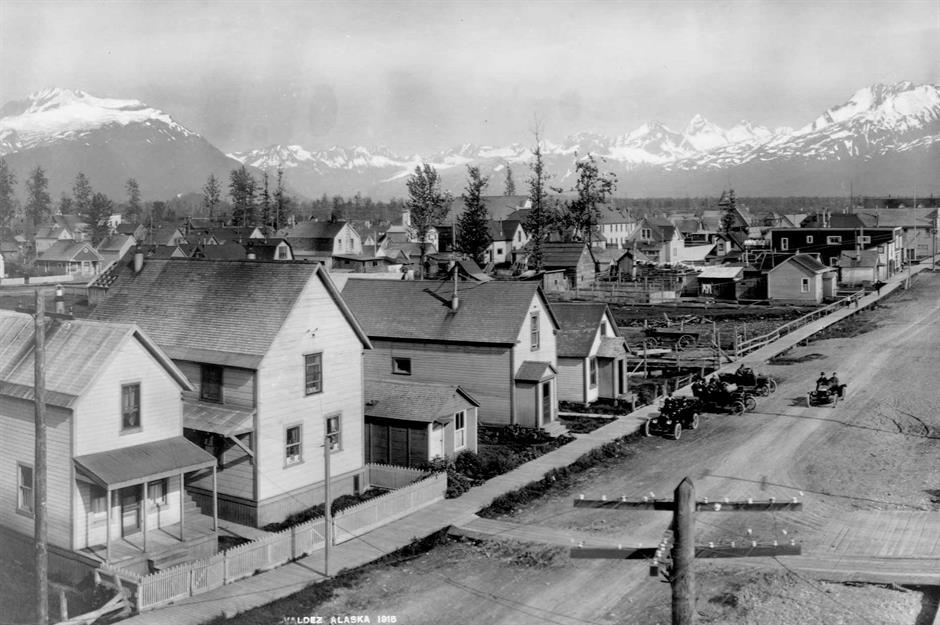

1915: a suburban street in Valdez

The suburban streets of the port city of Valdez in southern Alaska are captured here in 1915, their quaint clapboard exteriors, porches, and white picket fences reading like a slice of Americana.

The area had been scarcely populated before the gold rush, resulting in the hasty construction of a tent settlement that transitioned into a permanent city.

The mining and shipping industries bolstered the town's economy, and some settlers chose to lay down roots here. Between 1910 and 1920, the streets bustled with two movie theatres, a bowling alley, a bank, a library, a hospital, and a school.

1916: Mrs Brandt's home in Fairbanks

Fairbanks in Alaska's interior region was another gold rush outpost that transitioned into a vibrant settler community. By 1905, the newly incorporated city had a three-storey tower block, stores, saloons, a church, a hospital, and its own police and fire service, plus electricity and a sewage system.

Photographed here is the charming Fairbanks home of Mrs Brandt. Documents suggest that she could've been Margaret Anna Brandt, who relocated to the city to work as a telephone operator. In fact, Fairbanks' Brandt Street, which still exists today, is reportedly named after her.

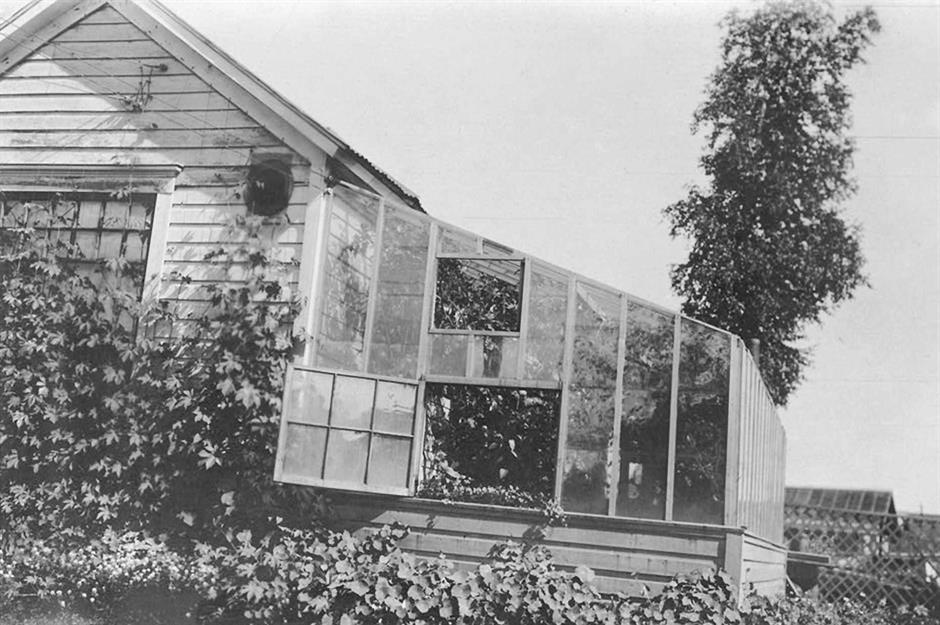

1910s: Mrs Frank Clark's greenhouse

This greenhouse, captured in the 1910s, was part of another property in Fairbanks, belonging to Mrs Frank Clark. Attached to a clapboard home, the glass construction is brimming with plants. Judging by the outbuildings visible in the distance, it may have been part of a larger agricultural acreage.

When the Homestead Act was extended to Alaska in 1898, it gave miners and other settlers a route to securing land in the territory. Swathes of homesteaders chose to settle in Fairbanks and farm the land. The city even had its own Land Office, where those interested could stake their land selection.

Sponsored Content

1916: inside the Tanana Club

Thought to have been a social space for the area's prospectors and businessmen to relax and unwind, this image of the Tanana Club in Fairbanks was captured in 1916. The space features regal armchairs, patterned floors, and bistro chairs, while artwork incorporating the US flag on the wall makes it clear that settlers frequented the establishment.

The extension of the Alaska Railroad was a game-changer for Fairbanks. In 1915, President Wilson announced the construction of a 500-mile (805km) route from Seward on Alaska's south coast to Fairbanks. The line was completed in 1923, transforming the area's economic prospects.

1918: an Aleut family poses outside their home

Taken in 1918, this colourised image shows a large family gathered outside their clapboard home on St George, one of the Pribilof Islands. The photograph identifies the family patriarch as Peter Prokopiof, an Aleut man born on Attu Island, the most remote of the Aleutian Islands.

By the autumn of 1918, the Spanish flu epidemic had arrived in Alaska. It was devastating for Native Alaskans, who had lived remote existences and were especially vulnerable to disease.

Around 82% of deaths caused by the flu were in Native communities, giving Alaska one of the world's worst death rates during the epidemic.

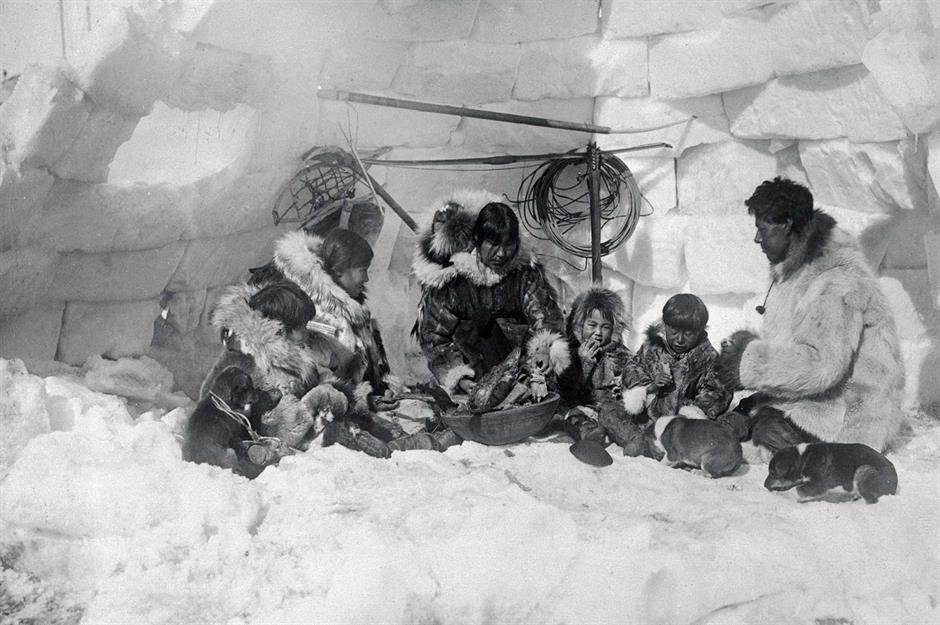

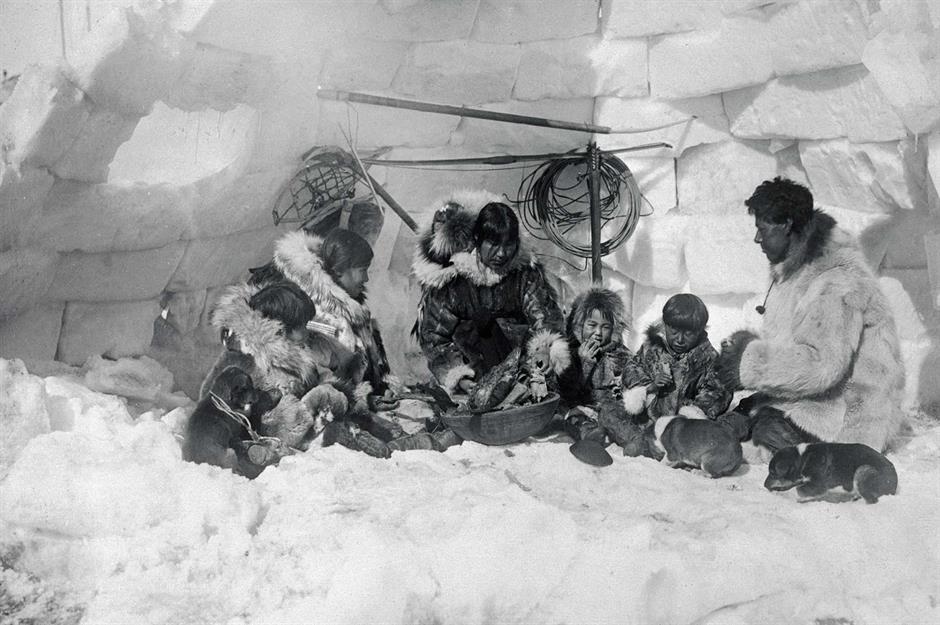

1924: Inuit peoples building an igloo

Photographed here in 1924 is an Inuit family constructing an igloo from blocks of hand-carved ice. Igloos are the traditional winter homes of the Native Alaskan group, and their distinctive domed structure offers protection from extreme weather.

Their construction is skilful, involving circular layers of ice blocks, each shaved to create a sloping angle that spirals upwards. A hole is left at the top of the igloo for ventilation, while snow is compacted into any crevices.

For an experienced builder, it could take between one and two hours to erect an igloo.

Sponsored Content

1920s: the interior of an ice-block house

This image from the mid-1920s shows the igloo's interior. A narrow passageway for storing supplies usually leads into the ice-block structure, which was historically furnished with a low ice sleeping platform covered in willow twigs and furs.

Alaska Natives were granted full American citizenship in 1914; however, as more newcomers arrived in the territory, it became more and more difficult to protect their ancestral lands and ways of life. By the time Alaska became a US state in 1959, Indigenous people made up only 19% of the population.

Loved this? Discover more incredible photographs of historic homes

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature