Inside Kenwood House – the home of Dido Elizabeth Belle

Discover the secrets of this stately home on London's Hamstead Heath

Nestled in the heart of Hampstead Heath, like a sumptuous wedding cake overlooking lush rolling acres, sits Kenwood House. The estate has been home to countless historical figures over the centuries, from a Lord Chief Justice to an Irish business titan of the Guinness brewing company.

However, it was perhaps its most famous resident, Dido Elizabeth Belle, whose remarkable story put Kenwood on the map.

Click or scroll to discover more about Dido Belle and her English country estate in the heart of London…

The many faces of Kenwood House

Kenwood House boasts a long and storied history of ownership and has undergone many iterations and alterations over the centuries. The first stately home on the site was actually a brick structure, originally built by John Bill, King James I’s printer, who bought the estate in 1616.

The estate changed hands several times over the 17th and 18th centuries, with its various owners making numerous additions and changes to both the house and grounds.

William Murray takes up residence

In 1754, the house was bought by William Murray, who, from 1756, served as the Lord Chief Justice. In spite of their childlessness, Lord Mansfield and his wife, Elizabeth (Betty), decided to expand the villa, which became something of a passion project for them both.

Lady Mansfield wrote in a letter to her nephew in May 1757, “Kenwood is now in great beauty. Your uncle is passionately fond of it. We go thither every Saturday and return on Mondays but I live in hopes we shall now soon go thither to fix for the Summer.”

Sponsored Content

Changes commissioned at Kenwood

Acquired for just £4,000 – or approximately £744,921 ($993k) in today’s money – the house became the weekend abode for William and Elizabeth.

In 1764, Mansfield went so far as to commission the famed Scottish neoclassical architect Robert Adam and his brother James to remodel the house, a project which lasted a shocking 15 years. Adam’s designs are still largely on display throughout the home today.

Adam's designs

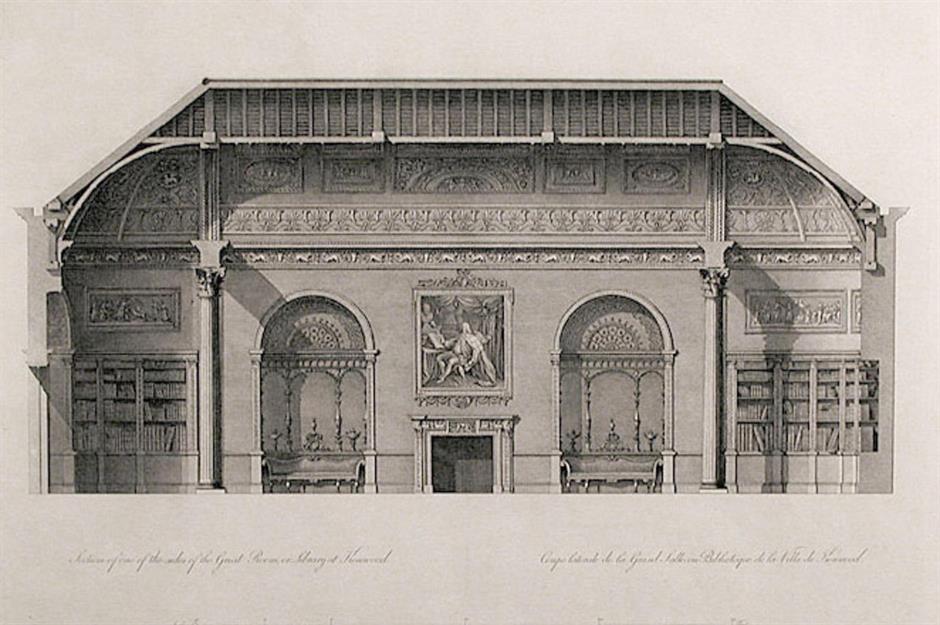

While the complete extent of the changes Adam made is not known, when he published the designs for Kenwood in 1774 (one of which is pictured here), the architect claimed that Lord Mansfield "gave full scope to my ideas”.

Some of these included the addition of a new entrance on the north front, a significant modernisation of the interiors, particularly the entrance hall and Great Stairs.

The family entertaining spaces, too, were given a modern decorative treatment, including the drawing room, parlour, a room dubbed ‘My Lord’s Dressing Room' and a newly created Great Room for entertaining.

An illegitimate arrival

Just two years after Adam began his renovations, in 1766, the Murrays agreed to take in their niece, Anne Murray, and two great-nieces, Elizabeth Murray and, perhaps Kenwood’s most famous resident, Dido Elizabeth Belle.

The illegitimate daughter of Mansfield's nephew, Sir John Lindsay, and a formerly enslaved black woman by the name of Maria Bell, Dido could easily have been ostracised from society for her mixed race and unconventional birth, but the Murrays agreed to take her in and raise her as their own.

Sponsored Content

Mysterious parentage

It is unknown how Lindsay, a Royal Naval Officer (pictured here), first encountered Maria, but their meeting likely occurred while Lindsay’s ship was sailing around the coasts of Senegal and the Caribbean in 1760.

It is believed that she was just 15 years old when she gave birth to Dido in 1761. There is very little information about Maria, though records suggest she may have been enslaved on a Spanish ship captured by Lindsay and brought to England, where she was freed and later sent to America, where she had been granted land to build a home.

Dido and Elizabeth

At the age of five years old, Dido arrived at her great uncle’s residence along with her cousin, Lady Elizabeth. Here, she held the position, not of a servant, as might have been expected of a child in her circumstances at the time, but as a member of the family and close companion to her cousin.

The two are pictured here in the famous painting by British artist David Martin, which depicts them as elegant, intimate young women and, more importantly, equals.

A ladylike upbringing

Raised as ladies, both girls were taught to read, write, play musical instruments, and behave with all the social graces expected of women of their class, both in the privacy of the family and while entertaining guests.

In John Lindsay’s obituary in the London Chronicle, it was noted that Dido’s “amiable disposition and accomplishments have gained her the highest respect from all his Lordship’s relations and visitants”.

Sponsored Content

Stately responsibilities

In addition to being granted a small annual allowance, Dido also held substantial responsibilities surrounding the running of the estate, a role which speaks not only to her competence and intelligence, but also to her respected position as a lady of the house.

In her youth, she was in charge of supervising the dairy and poultry yard, but took on still more domestic responsibility after the death of Lady Mansfield in 1784, and the marriage of her cousin the following year.

Flying the nest

By 1785, Dido was the sole lady of Kenwood House, in charge of both the care of her elderly uncle and the management of the estate. She remained by her uncle’s side at Kenwood until his death in 1793. He left her an annuity of £100 ($133) and a lump sum of £500 – around £63,300 ($84.3k) in today's money. This was a smaller amount than given to her cousin Elizabeth, but this may have been due to Dido's illegitimate status.

Only then did she begin her own life, marrying a steward of French extraction by the name of John Danvier, and finally moving away from Kenwood to Pimlico, where the couple had three sons. She passed away at the age of just 43.

Significant changes

After the 1st Earl’s death, Kenwood passed on to his nephew, David Murray, Viscount Stormont, who quickly embarked on some substantial changes to the property.

Perhaps most significantly, the 2nd Earl commissioned little-known architect George Saunders to build the north-east and north-west wings, which would become two of Kenwood’s most striking spaces: the music room and the dining room, pictured here.

Other additions included a service wing with kitchens, bedrooms, a brewhouse, and a laundry, as well as new gate lodges, a new farm, stables, and a dairy.

Sponsored Content

A new outlook for Kenwood

It was under the 2nd Earl, too, that the grounds and gardens at Kenwood began to take the shape we know today.

In collaboration with famed landscape architect Humphrey Repton, the 2nd Earl commissioned a complete remodel of the grounds, creating a system of meandering paths around the estate to offer a variety of pleasant walks, all of which show off the house to its best advantage.

Repton also dramatically altered the views from within the house, breaking up the sweeping vistas of rolling parkland by planting several groves of trees.

More alterations

In 1815, Kenwood passed into the hands of the 3rd Earl, David William Murray, who was just 19 years old when he took up the title.

Young though he was, David already had his own ideas to improve the estate, and hired architect William Atkinson to make several alterations, including the addition of second-floor rooms to the service wing and the installation of bookcases in the mirrored niches in the famous library, pictured here.

Preferring the Scottish seat

The 3rd Earl was also responsible for the insertion of the large French windows in the music room, pictured here. However, during the 19th century, the Mansfields preferred to live at their Scottish residence, Scone Palace, where the famous portrait of Dido and Elizabeth resides today.

The family would diligently return to Kenwood for three months a year, however, preserving the tradition and family connection to the estate.

Sponsored Content

Kenwood becomes a rental

Kenwood underwent a substantial change in both ownership and circumstances in the 20th century, when the 6th Earl of Mansfield, who had inherited the estate from his brother in 1906, decided to sell it after just eight years.

The Earl, Alan David Murray, had never considered Kenwood home and had been renting the house to tenants since 1909. Some of the illustrious occupants included Grand Duke Michael Michaelovitch, second cousin to the last Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, who lived there until 1917.

Kenwood's contents are lost

The Grand Duke and his family were followed by American millionairess and ‘dollar princess’ Nancy Leeds, who remained in residence until her marriage to Prince Christopher of Greece in 1920.

As Kenwood entered the Roaring Twenties, when London high life beckoned and large country manors floundered in the disillusioned practicality in the wake of the First World War, the estate’s future seemed to be in jeopardy.

In November 1922, Lord Mansfield sold off all the home’s contents, including some of the original furnishings.

Guinness to the rescue

However, in 1925, Kenwood was rescued and its future ensured by wealthy Anglo-Irish philanthropist and businessman Edward Cecil Guinness, 1st Earl of Iveagh.

Most famous for serving as the head of the eponymous Irish brewing company, Guinness purchased Kenwood and the surrounding 74 acres (30ha).

In 1929, the Iveagh Bequest Act stipulated that Kenwood and its grounds should be opened to the public free of charge, with the ‘mansion and its contents … preserved as a fine example of the artistic home of a gentleman of the eighteenth century’.

Sponsored Content

Guinness's art collection

While Kenwood’s original furnishings had been lost during the 1922 sale, with Guinness’s patronage came his prestigious collection of 63 Old Master and British paintings, the majority of which are still on display today.

Guinness himself never lived at Kenwood, but had purchased several other properties in Hampstead since the turn of the century, and was actively invested in preserving the community.

Sadly, Guinness died just two years after buying Kenwood, never having had the chance to refurnish the house.

Repair and restoration

Like so many English stately homes, Kenwood took on new life during World War II, housing servicemen. In 1949, the house was found to be in dire need of repair and was handed over by the Iveagh Bequest Trustees to the London County Council.

By 1986, the home had been taken over by English Heritage, which maintains and preserves it to this day.

Kenwood today

In 2012, English Heritage undertook an extensive repair and conservation project, which included the repair of the Westmorland slate roof and the redecoration of the exterior and interior of the house, based on new paint research into the original Adam scheme.

Kenwood was reopened to the public in 2013, and English Heritage attempts to preserve the home as it might have looked under 17th-century ownership, or as Dido Belle would have known it.

Loved this? Now discover more magnificent stately homes

Sponsored Content

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature