Tour the beautiful town where rent is less than €1 a year

This historic town hasn't raised rent in 500 years

While the cost of living continues to soar across the world, one town in southern Germany is something of an outlier. Rent in the Fuggerei, the world's oldest social housing complex in existence, hasn't been raised in over 500 years.

Founded in 1521 by a wealthy merchant, the community was designed to provide dignified homes for those in need. Today, residents still pay a symbolic annual fee of just 88 euro cents (77p/$1) to be part of the unique settlement.

Click or scroll on to discover the town's fascinating history and the lives of its residents, past and present...

A sanctuary in the heart of the city

Nestled within the Bavarian city of Augsburg, the Fuggerei is its own contained world, defined by rows of sloping terracotta roofs and ochre façades. A wall secures the boundary of the town, keeping the historic enclave at a distance from the urban sprawl around it.

The Fuggerei encompasses 3.7 acres (1.5ha), which includes 67 buildings, 142 apartments, and a church. Founded back in 1521, it was planned as a sanctuary for Augsburg's poorest Catholic residents facing financial hardship. Much has changed since its inception five centuries ago, but the town continues to support a population of 150 low-income tenants.

The vision of a philanthropic merchant

The Fuggerei was the vision of Augsburg merchant and philanthropist Jakob Fugger. One of the most successful financiers of his generation, he was known as Jakob Fugger the Rich.

Work began on the town in 1516, followed by its official founding five years later. In the deed, Fugger declared that the community should be a home for Augsburg's needy "forever and ever". Following Jakob Fugger's death, his nephew, Anton Fugger, completed the settlement's construction in 1525.

The town is still run by the Fugger Foundation and the Fugger family. Money for its maintenance comes from the family's investments in forestry and real estate, as well as entrance fees to the town's museums.

Sponsored Content

An enduring ideology

This picture postcard from 1907 captures the Fuggerei's main thoroughfare, which looks very similar to the street today, from the unusual stepped roof gables to the quaint shuttered windows.

The town's eligibility criteria have also remained largely the same for more than 500 years. Underpinned by Jakob Fugger's founding ideology, residents must be Catholic, have lived in Augsburg for at least two years, and be able to demonstrate financial need.

Applicants who meet these requirements can apply for an apartment for the symbolic annual rent of 88 euro cents (77p/$1). This equates to one Rhenish guilder, the original fee established in the 1520s in the Rhineland's historic currency. The rent has never been adjusted for inflation.

A casualty of war

While the town's architecture is faithful to its origins, large swathes of the Fuggerei had to be rebuilt following extensive bombing during World War II. Almost 70% of the community was destroyed – the devastation is captured in this photo from 1945, which depicts rubble-strewn streets, shattered windows, and smouldering ash piles.

The Fugger Foundation sold wood from its forests to finance the Fuggerei's reconstruction, which began almost immediately. The fabric of the town may not be wholly the same as it was in the 16th century, but its historic spirit has been successfully restored. Let's take a look around the Fuggerei today...

Strict admittance rules

The walled town is accessed via seven gates, emblazoned with blue and white stripes. However, there are restrictions on when you can enter or leave the community. A rule in place for over 500 years dictates that the gates must close between 10pm and 4:30am. During this period, returning or departing residents can use the Ochsengasse gate, but they must tip the night watchman 50 euro cents (44p/59¢) before midnight or €1 (87p/$1.17) after midnight.

The night watchmen are usually citizens of the Fuggerei. As specified in the 16th-century guidelines, residents are expected to take on jobs to support the community. Other positions include volunteering as gardeners, and, in more recent decades, ticket sellers for the town's tours and museums.

Sponsored Content

An early emblem of the town

Situated in the heart of the town's main street, this fountain has become an emblem of the Fuggerei. It's seen numerous iterations over the centuries, beginning with a wooden fountain constructed in 1599, which served as the community's first free-to-access water supply. The cast-iron design we see here dates from 1846.

A well master was appointed in 1715 to maintain this vital resource and keep the water supply and pipes clean and in good working order, as well as monitor the town's rudimentary drainage system.

A door of one's own

Accommodation in the Fuggerei was carefully planned to give residents a sense of independence. Each house comprises an upstairs and downstairs apartment. Rather than having a shared entrance, each apartment has its own front door leading directly onto the street. For the ground-floor apartments, the door opens into the unit's hallway, while the doors of upper-floor apartments open to a staircase that leads to the main living space.

Not only does this design afford residents more privacy, but during more conservative periods in the town's history, it also made it easier to monitor the comings and goings from each apartment.

Notable historic residents

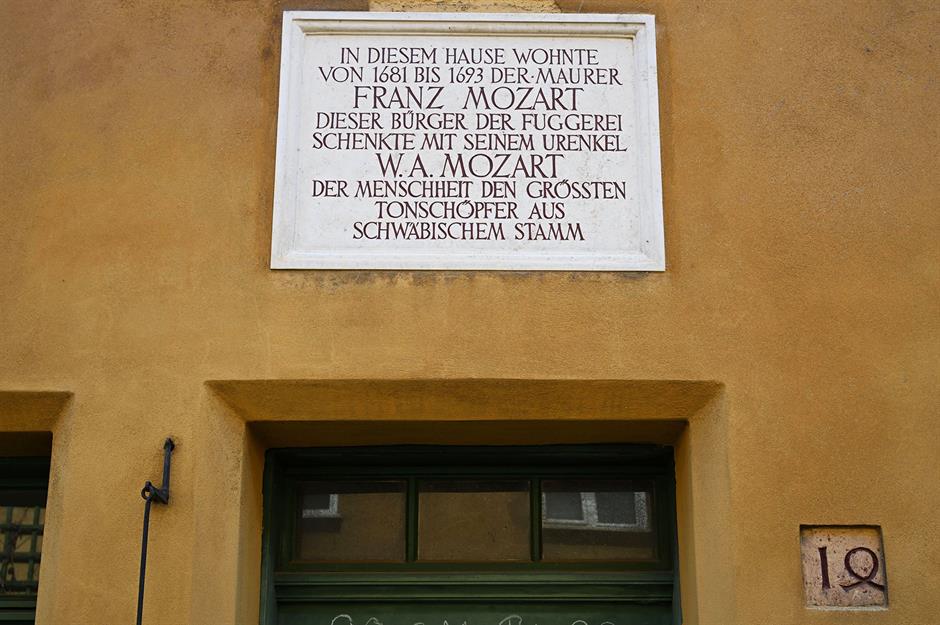

Over the centuries, the town has offered sanctuary to prominent names. This plaque marks the home of Franz Mozart, the great-grandfather of the Austrian composer Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. Franz, who worked as a bricklayer, moved into the upstairs apartment of house 14 in 1681 with his family. He lived in the Fuggerei for 13 years before his death in 1694.

On the right of this photo, you can see a stone marker engraved with Gothic numerals that read 14. From 1519, the oldest homes in the Fuggerei were numbered in this way. Due to the destruction wreaked by World War II, it's unclear which of the numerals are original. Following the conflict, markers were chiselled into the brickwork to replace those lost.

Sponsored Content

Stepping back in time

The door to the ground-floor apartment in house 14 leads to a remarkable home that shows how residents may have lived in the 16th century. Parts of the unit originate from 1517, while the furnishings are based on historic records.

Open to the public as a museum, the extraordinary home comprises a kitchen, a living room, and a bedroom. Pictured here, the living area features rustic exposed beams overhead, a grandfather clock, and a humble bench and dining table.

Back in 1521, the Fuggerei had 52 buildings occupied by families, many of whom were craftspeople who worked in their living quarters. A sitting area like this would likely've doubled as a workspace for many residents.

A rustic kitchen

The central room in the apartment, the kitchen was strategically located to warm the rest of the home. A stove built from bricks and fuelled by firewood provided heat for cooking. Laundry would also be washed in this room.

Afra and Jörg Holzwart were among the first residents to move to the Fuggerei in 1520. Jörg was a woodcutter who had moved to Augsburg in 1515. However, as he was not a citizen of the city, he was subject to punishingly high taxes. Living in the Fuggerei, Jörg was able to save enough money to purchase citizenship.

According to the contract between the Fugger family and the city of Augsburg, the Fuggerei is exempt from tax, provided that the annual rent doesn't exceed one Rhenish guilder – equivalent to the weekly salary of a tradesman in 1521.

A 16th-century bed chamber

Elsewhere in the apartment, this recreation of a 16th-century bed chamber features a coffered wooden ceiling and a four-poster canopy bed, adorned with elaborate illustrations of religious icons.

Apartments in the Fuggerei may have drastically different furnishings and amenities today compared to the 1500s, but the compact scale of the homes is very similar. Apartments vary in size from 500 square feet (47sqm) to 700 square feet (65sqm). However, units these days come with modern fitted bathrooms and kitchens as standard.

Sponsored Content

Desirable outdoor space

While upper-floor apartments feature attics, the ground-floor apartments have private gardens or yards – a benefit that makes this type of accommodation the most desirable option among the Fuggerei's modern residents.

In the town's early history, tenants often constructed workshops in this extra outdoor space to support their income. Some yards also accommodated stables and sheds for small livestock, alongside firewood stores. Those lucky enough to have gardens utilised these spaces to grow vegetables and fruit to feed their families.

A novel way to navigate at night

The streets of the Fuggerei are filled with historic idiosyncrasies that may not immediately make sense to contemporary eyes. A particularly unusual fixture is the metal bell pulls installed outside the front doors of the apartments, some of which are still operational. Each design is unique to the home.

The bell pulls originate from centuries past, before the streets were illuminated at night. The different handles were conceived as a novel way to help people find their way home after dark. Residents would simply feel their way along the street until they found the bell pull handle distinct to their property.

Antique illumination preserved

With the arrival of nine gas lamps in the Fuggerei in 1864, residents no longer had to use the bell pulls for nightly navigation. Street lighting was electrified in the town in 1976; however, six of the 19th-century lamps were connected to the municipal gas supply, preserving this method of antique illumination. They're now the last gas lamps in operation in Augsburg.

Alongside the street light, this photograph shows an alcove housing a statue of a saint inset into the exterior of a home. Across the town, there's a total of 17 patron saints and Madonnas incorporated into residential façades. The Fuggerei's Catholic population believes the statues offer protection for the home's inhabitants.

Sponsored Content

The town's spiritual centre

The town plan has fluctuated throughout the decades to accommodate the changing needs of its residents. The 16th century saw the opening of a hospital ward in one of the houses, while in the mid-17th century, a Catholic school was established. Neither is in existence today.

But some additions have stood the test of time, namely St Markus's Church. The simple building was constructed between 1580 and 1582, after the local Catholic church used by residents became Protestant during the Reformation – a period in which Catholics faced persecution.

Salvaged from the ruins

Sadly, the church was badly damaged during bombing raids in 1944 and was largely rebuilt in 1950. Religious and architectural elements were salvaged from the surrounding area and repurposed, such as the crucifix altarpiece, which dates from around 1595. A stand-out feature, the 16th-century coffered ceiling with its exquisite marquetry is thought to have been taken from the Fugger Foundation House near St Anna's Church in Augsburg.

Worship has been a central part of daily life in the Fuggerei since the town's inception. The original rules from the 1500s stipulate that residents must say three prayers a day for Jakob Fugger and the current Fugger family, something that is still observed today.

An architectural patchwork

Pictured here is the Senior Council Building, situated by the town's main gates. It was decimated by bombings in World War II and reconstructed in 1950. Like the church, the rebuild incorporated fixtures from important historic structures in Augsburg that had been reduced to ruins in the war. For example, this magnificent double-height bay, known as an oriel, was rescued from the local area and integrated into the edifice to ensure its preservation.

Today, the upper floor of the Senior Council Building is used for meetings of the family board responsible for the running of the various Fugger Foundations. In more recent years, a restaurant has operated on the ground floor to accommodate growing numbers of tourists.

Sponsored Content

The town's air-raid shelter

As we've seen, World War II was one of the most destructive chapters in the Fuggerei's history. During this fraught period, when Germany was at war with the Western Allies, including France, Great Britain, and the US, the Fugger family constructed a bunker to keep the townspeople safe. The air-raid shelter was completed in late 1943, and its unassuming shed-like entrance is pictured here.

Months after its construction, the bunker was put to use on the night of 25 February 1944, when a bombing raid decimated the area. Some 200 Fuggerei residents took shelter in the subterranean complex until the attack was over. The siege resulted in the deaths of 730 people in Augsburg.

A changed community

Inside, the sprawling concrete bunker features a fortified entrance door with a gas seal to keep out airborne toxins. The space still includes pipework and fixtures from its time as an active air-raid shelter, but it's since been turned into a museum that explores the impact of the war on the Fuggerei. Original items from the period are on display, including gas masks, equipment, and old signage.

Following the Second World War, two new accommodation buildings were constructed in the Fuggerei to house women who had lost their husbands during the conflict.

Meet the Fuggerei's current residents

Today, residents of the Fuggerei range from struggling retirees to families and young people priced out of the housing market in Augsburg, which is just an hour from Munich, Germany's most expensive city.

Martha Jesse, photographed here by her front door in 2025, has called the town home for 17 years. She applied to the social housing scheme after retirement, when she found herself struggling to live off her monthly pension of just €400 (£349/$469), despite working for 45 years. "Living elsewhere would have been almost impossible", she told French news platform France 24.

Sponsored Content

A modern home with historic roots

Martha's compact ground-floor apartment has a similar floor plan to the town's original 16th-century lodgings, but it's perfectly equipped for modern living. The lounge features an orange corner sofa and a colourful patchwork rug, and the hallway includes space-efficient storage for hanging coats and outerwear.

Speaking to online German news outlet ORF Topos, Martha revealed that moving to the Fuggerei has given her the financial freedom to treat her grandchildren to trips to the cinema, and go away on holidays with other residents from the tight-knit community.

A lingering legacy

Alongside the religious iconography that decorates Martha's home, a portrait of Jakub Fugger hangs prominently in the hallway. The presence of the Fuggerei's philanthropic founder is still keenly felt by current residents – a bronze bust of the businessman even presides over one of the town squares.

While securing a home in the community is life-changing, they're hard to come by. Augsburg social worker Doris Herzog told Canadian broadcaster CBC that the waiting list is long. For ground-floor apartments like Martha's, which are the most sought-after, applicants can wait five to seven years.

Embracing a 500-year-old blueprint for social change

The question of how society can provide dignified, affordable housing for those in need has long been a hot topic of conversation. But the Fuggerei represents an extraordinarily successful prototype that's flourished for over 500 years. Countries around the world are taking note, with studies being carried out for similar initiatives in Lithuania and Sierra Leone.

There are no plans to change the historic rules that the Fuggerei was founded on, including its 88-cent (77p/$1) annual fee. "Increasing the rent would defeat the core purpose", Count Alexander Fugger-Babenhausen, a descendant of Jakob Fugger, told CBC.

Loved this? Discover the fascinating stories behind more historic homes and communities

Sponsored Content

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature