The grandest estates of America's 'dollar princesses'

Meet the women who saved British aristocracy

By the late 1800s, countless estates across the United Kingdom were struggling. Centuries of financial mismanagement, death duties, the unending cost of repairs and maintenance, and the inevitably shifting economic landscape left many families unable to keep up with annual expenses. It put their estates at risk of being broken up or sold off entirely.

And with intense social stigmas preventing members of the aristocracy from actually taking on employment, the landed gentry were left with only one option when it came to saving their ancestral homes: marrying for money.

Click or scroll to learn about the American women who saved the homes of the British Lords and Dukes struggling to make ends meet...

Gilded Age heiresses

Across the Atlantic, an entire generation of wealthy heiresses was coming of age. American industry had boomed during the 19th century, dubbed the Gilded Age to reflect the prosperity achieved through the expansion of railways, shipping, banking, and other lucrative industries.

However, while the ‘Robber Baron’ tycoons might have had everything money could buy, they were hungry for the one thing it couldn’t: a title.

Wealthy Americans worshipped European old-world elegance, viewing English aristocratic society as the epitome of status and power, and hankering after a piece of it.

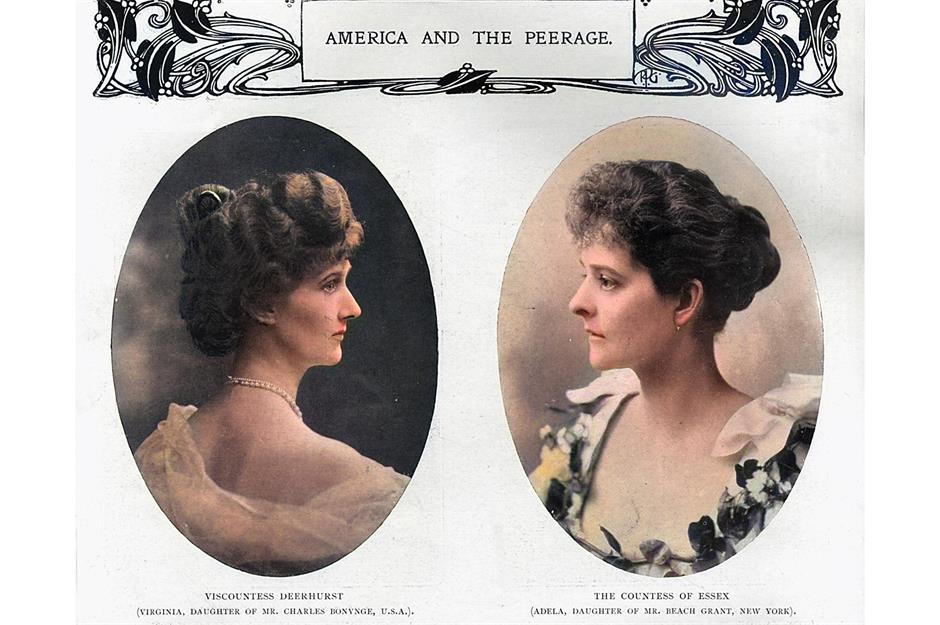

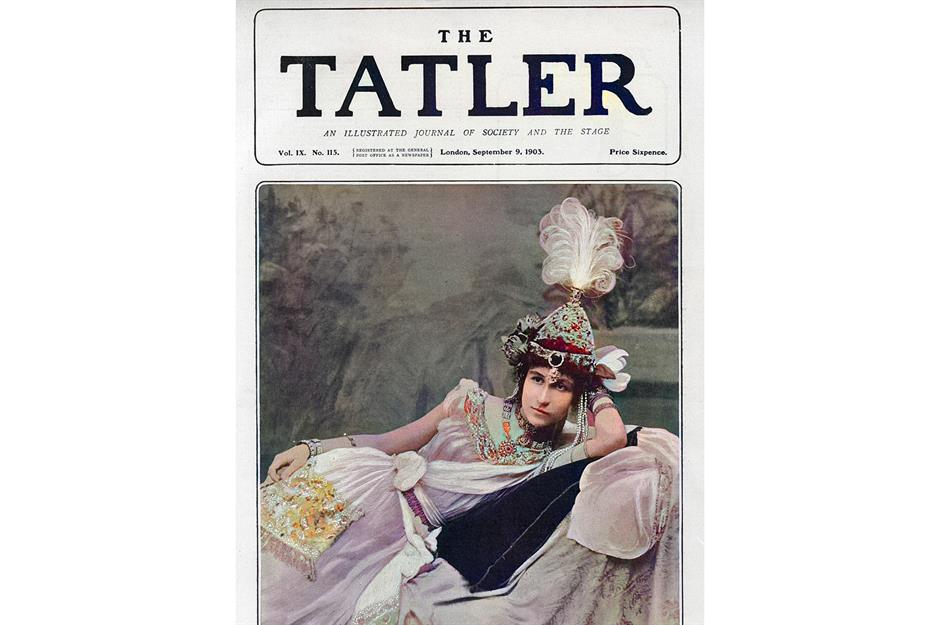

Famous faces

The result was what could be interpreted as a match made in heaven: wealthy American heiresses exchanged their millions for the title and status offered by impoverished English lords.

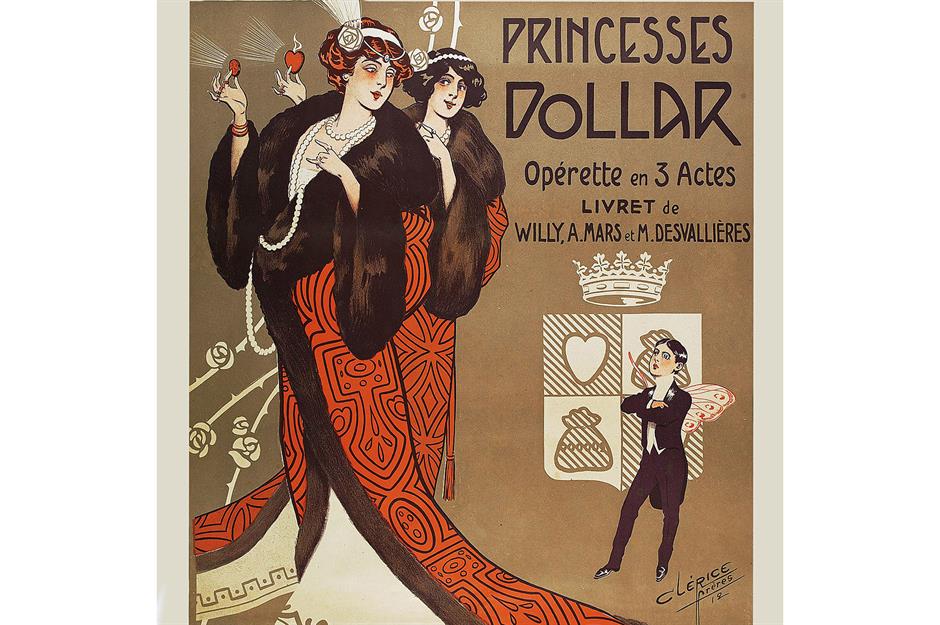

Indeed, so many of these matches took place in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that they captured the public's interest, who dubbed the imported heiresses ‘dollar princesses'.

These women and their high-profile marriages featured prominently in women’s magazines, inspired caricatures and theatrical works, and were even the basis for Edith Wharton’s unfinished novel, The Buccaneers.

Inconvenient marriages of convenience

While many of these women eased effortlessly into their roles, others were less successful in making the transition. These were, after all, marriages of convenience, and the bold, modern sensibilities of American new money often clashed with the more stately and old-fashioned traditions of the British aristocracy.

Moreover, sometimes even the heiresses’ millions weren’t enough to salvage the foundering estates, leaving the ‘princesses’ both homeless and purposeless in a strange land. But just who were these ‘dollar princesses’, and what grand estates were they imported to save?

Consuelo Montagu

The true inspiration for Wharton’s novel is widely acknowledged to be Consuelo Montagu, who was a close friend of Wharton’s in New York.

Consuelo was of Cuban American descent, the daughter of diplomat Don Antonio Modesto Yznaga y del Valle and his wealthy Louisiana-born wife, and was introduced to her future husband, George Montagu, heir to the 5th Duke of Manchester, at her father's New Jersey estate.

Consuelo’s dowry put £200,000, or roughly £20.1 million ($26.7m) in today’s money, towards settling her gambling-addicted husband’s debts.

Kimbolton Castle

After they were married in 1876, Consuelo and her husband spent 14 years at Tandragee Castle in County Armagh before finally moving to the family seat of Kimbolton Castle near Cambridge, when George inherited the Dukedom.

Thanks to Consuelo’s millions, there was still an estate to inherit, and the couple were able to live the lavish lifestyle worthy of their social status.

The castle itself had been the family seat of the Dukes of Manchester since 1615, and before that was famously the final home of Queen Katharine of Aragon, the first wife of Henry VIII.

Kimbolton Castle

Between 1690 and 1720, the castle had been largely rebuilt at the behest of Charles Edward Montagu, 1st Duke of Manchester, who commissioned it in the fashionable classical style.

However, Charles was eager to ensure the design had ‘something of the Castle Air’ given its long history as merely a fortified manor house, resulting in the battlements.

He also hired celebrated Venetian artist Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini to decorate the castle’s interiors with many spectacular frescoes, including the one on the walls and ceilings of the main staircase, pictured here.

Margaretta Drexel

Brought up between Philadelphia and London, Margaretta Armstrong Drexel was heiress to the immense Drexel banking fortune established by her grandfather in partnership with financial tycoon J.P. Morgan.

Margaretta was 'brought out' in London in 1907, whereupon she immediately received numerous proposals from Europe’s most eligible, titled, and fortune-hungry bachelors, but ultimately accepted Guy Finch-Hatton, Viscount Maidstone.

The couple was married in 1910 in front of 1,500 guests and an additional crowd of 8,000 onlookers, many of whom wanted to catch a glimpse of the jewellery worn by the bride, estimated to be worth several hundred thousand dollars.

Haverholme Priory

After their marriage, the couple lived in Grosvenor Square, first with Margaretta’s parents, then in their own home.

The Earls of Winchilsea, of which Guy was to become the 15th, had given up their ancestral seat at Kirby Hall in 1835, but had taken up residence in the stately Haverholme Priory in Lincolnshire.

The 10th Earl had built the Gothic Revival-style mansion on the site of a monastery dating to 1139 that had been dissolved under King Henry VIII in 1539.

Haverholme Priory

The Priory served the family up through Guy’s father, who kept a pet lion there, allowing it to wander the halls like a house cat.

However, in spite of the financial bolstering the family estate received from Margaretta’s millions, Guy and his father opted to sell the Priory in 1926 to an eccentric American lady who had it disassembled and prepared to ship to the US, where she intended to rebuild it.

Before the stones could be shipped, however, the lady was killed in a train accident, and the unclaimed cargo was unceremoniously used to build docks.

Mary Leiter Curzon

The daughter of a wealthy Washington DC-based merchant, Mary Leiter grew up in a well-educated, cultured household. When it came time for her to marry, she selected, from among an array of potential partners, George Nathaniel Curzon, a member of the British Parliament and a diplomat.

As if these qualifications weren’t enough, three years after their marriage in 1895, Curzon was appointed Viceroy of India and created Baron Curzon of Kedleston, making Mary Baroness Curzon and Vicereine of India, the highest political rank attained by an American woman at the time.

Kedleston Hall

While the couple’s diplomatic responsibilities kept them in India for extended periods of time, the Curzons did hold a family seat, Kedleston Hall, in Derbyshire. The Hall was commissioned in the 1750s by Nathaniel Curzon, 1st Baron Scarsdale, whose ancestors had resided in the region since the 12th century.

Curzon appointed renowned architect Robert Adam, who designed the home in the Palladian style, with the intention of paying homage to ancient Greece and Rome. While Mary sadly died in 1906, 10 years before George inherited Kedleston, her vast dowry went a long way towards ensuring the future of the Hall.

Kedleston Hall

Widely considered one of the best examples of neo-classical architecture in England, the Hall’s interiors are packed with an extensive collection of paintings, antiques, and elegant furnishings, many of which were designed by Robert Adam for Sir Nathaniel.

Under Mary and George’s occupancy, the home also filled up with an array of treasures acquired during their travels in the Far East.

Today, the home is owned and operated by the National Trust, and its collections are on display in its museum of Asian artefacts.

Mary Goelet

Second only to the Astors in their social cache and Manhattan property portfolio, the Goelet family boasted one of America’s most enviable fortunes.

Mary Goelet was perhaps the wealthiest of the dollar princesses, inheriting both an impressive art collection and roughly $28 million in the wake of her parents’ deaths, the equivalent of around $500 million (£375m) in today's money.

However, Mary was distinguished from her peers like Consuelo Vanderbilt in that she achieved a supposed love match with Henry Innes-Kerr, 8th Duke of Roxburghe, an eminently eligible member of the Scottish nobility.

Floors Castle

However, no matter the prestige of its family title, a Scottish castle is always in need of costly repairs, and Goelet’s fortune was quickly put to use to ensure the future of Floors, her husband’s family seat.

Floors Castle, situated on a 60,500-acre (24,483ha) estate in Roxburghshire, was commissioned in 1721 for John Ker, who had been created the 1st Duke of Roxburghe for helping to accomplish the Anglo-Scottish union of 1706.

Floors Castle

The fairytale-style castle was designed by architect William Adam to incorporate the old tower house that had previously been the Ker’s family seat, and was further embellished in 1837 to include turrets and battlements.

In 1903, Mary’s money helped refurbish the castle both internally and externally, and she improved the castle’s interior decoration, importing her own family’s treasures from America, including the Gobelin tapestries in the ballroom and several paintings by Matisse.

Today, the house is both the home of the 10th Duke and open to the public.

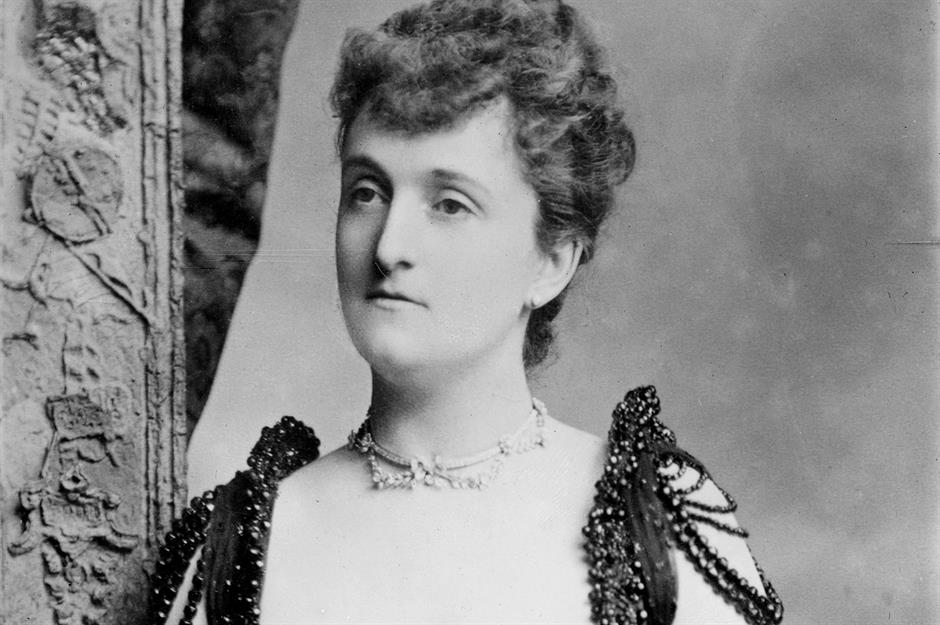

Jennie Jerome

Though perhaps more famously remembered as Winston Churchill’s mother, Jennie Jerome was a powerful heiress and socialite, daughter of the 'King of Wall Street' Leonard Jerome, who developed charm, wit, and worldliness through an upbringing split between New York and Paris.

Jennie married Lord Randolph Churchill in 1874, their marriage having been delayed two years while their parents argued over Jennie’s dowry.

A Tory MP, Randolph was the son of, but not the heir to, the 7th Duke of Marlborough, who held the family seat at Blenheim Castle.

Consuelo Vanderbilt

While Jennie’s riches may have helped stock the Churchill family coffers, it wasn’t until a generation later that American wealth was needed to rescue Blenheim itself.

In 1895, Consuelo Vanderbilt, heiress to the enormous Vanderbilt family fortune, was forced into an arranged marriage with Charles Spencer-Churchill, 9th Duke of Marlborough, who had, three years previously, inherited Blenheim Palace and its accompanying crippling debts.

Though Consuelo openly protested the marriage, her parents were eager to see her enter into the English aristocracy and reportedly locked her in her room until she consented to the match.

Blenheim Palace

The Duke, meanwhile, had negotiated a settlement of $2.5 million ($90m/£68m today) in Vanderbilt railroad stock, plus an annual allowance of $100,000 ($3.2m/£2.4m today) for himself and his future wife.

Though he supposedly despised anything ‘not British’ and was in love with another woman, he was relieved to ensure the future of his family’s ancestral seat with Consuelo’s fortune.

Blenheim, which had been in the Churchill family since it was gifted by Queen Anne in 1705, is one of the largest and grandest of England’s stately homes. It's the only one to be granted the title of ‘castle’ without any royal connections.

Blenheim Palace

A closer look at Blenheim makes it easy to understand why it took not one but two dollar princess fortunes to shore up the Churchill family finances.

The sprawling estate was designed by Sir John Vanbrugh, better known as a dramatist than an architect, in the controversial English baroque style. It was intended to serve as a family home, national monument, and mausoleum all in one, covering a total of seven acres (2.8ha). The palace was completed in 1722, and over the next 300 years, it was altered by members of the Churchill family, who remain its owners to this day.

Loved this? See more incredible historic homes

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature