What it's REALLY like to live in a Grand Designs house

After the initial dream of designing her own house became the reality of day-to-day life, has Geraldine Bedell’s self-build house stood the test of time?

It took nearly three years to buy the land, do the designs, get the planning permission and, finally, build the house. But 16 years ago, we moved into our brand new, self-built concrete, timber and glass modernist home in Highbury, North London.

READ MORE: Our favourite projects from Grand Designs

Our youngest child was two. Now he’s about to finish school, his brother is leaving university, and the two oldest have homes of their own.

Geraldine and her family - who have lived in their concrete self-build home for 16 years | Photo by Michael Donald

So how has our self-build dream fared, this house that was built around us, now that the ‘us’ has changed? Does it still feel like it was made-to-measure? Does it look as good as it did when it featured on the front cover of architecture magazines and won awards? And what mistakes did we make?

A learning curve...

The most noticeable thing about our house is that it’s made of poured concrete. All the structural walls are concrete slabs, rising up dramatically from the foundations. Fortunately, we like concrete – but you can’t puncture it because the walls would never be the same again. That means you can’t hang pictures. One of my regrets is that I didn’t think more carefully about art. When I occasionally think about moving, the main attraction is having lots and lots of paintings on my walls.

Poured concrete is almost impossible to hang pictures on, as Geraldine discovered

Designing a whole house, you make a lot of decisions quickly. Inevitably, you make mistakes. Our eldest son had a passion for stick insects and salamanders; the architects thought it would be great to have a kind of protruding glass slot in his bedroom wall, so that people walking up and down the stairs or along the upstairs hall could see his collection of insects and reptiles.

But three years is a long time in the life of a child. By the time we moved in, the stick insects and salamanders were long gone. My son put deodorants and moisturisers in the glass slot and complained that the last thing he wanted was people looking in his room. He hung up a blanket.

People want privacy in their bedrooms, I learned. Especially teenagers. One of my pieces of advice to self-builders would be do not put any tricksy-cutesy glass slots in your bedroom walls.

Beware over-customisation...

The architects would be the first to admit they were a bit controlling. Even after we’d moved in, they occasionally came round and moved photographs along the piano, because they didn’t like the way I’d placed them.

As a result of their keenness to think through every detail of the space, they specified custom-made beds and desks in the bedrooms. These were beautiful objects but, one by one, the children decided they hated them, they took up too much space, they didn’t like the storage underneath. They insisted on replacing them with beds from Warren Evans and desks from IKEA.

None of those mistakes is that major – and, in the case of the concrete, the upside is that it’s like a painting in itself. It’s like living with a late Turner seascape, all atmosphere.

An ongoing love affair

Light pours onto the walls, changing with the time of day and the seasons, endlessly interesting. There is a lot of light in the house, in fact – one whole side, onto the garden, is glass. (The architects imagined it as like a doll’s house.) We are unusually aware of the weather for Londoners. I would hate now, to live in a house where light didn’t feel like part of the construction.

Lots of glass lets light pour into the house and blurs the boundaries between indoors and the beautiful garden

The smooth grey walls (the concrete was poured into birch ply moulds) are curiously calming – and, thanks to the wealth of rich timber in the house, never feel cold or forbidding. In summer, the big downstairs doors open and the house seems to double in size.

So the big things – the materials, and the overall sense of space – still work. I love many of the smaller things too: the way the kitchen is at the centre of the house, its physical and emotional heart. The way the master bedroom is laid out: bedroom, bathroom, dressing room, so that the sleeping part is almost monkish, a kind of sleeping cave, uncluttered and private.

The kitchen is a dream and offers as much storage as anyone could want

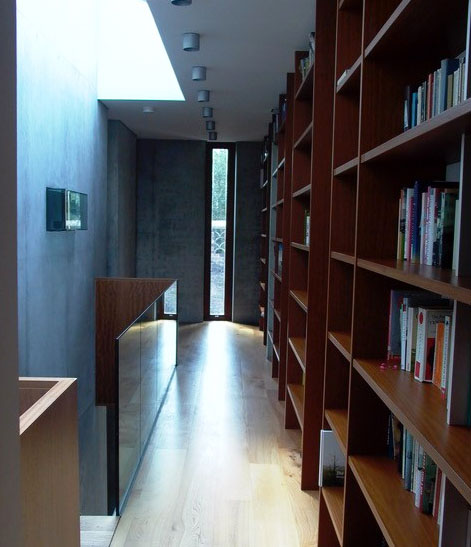

I love how much storage there is. The kitchen is partitioned by floor to ceiling cupboards and there are big wardrobes in every bedroom; the upstairs hall is lined with bookshelves. I thought it might be hard to live like a modernist (I am hopelessly untidy, though I dislike untidiness) but it turns out that it’s simply a matter of having enough places for everything to have a place.

The care with which everything was done has paid off. The kitchen is actually quite old now but looks (at least on casual inspection) in pretty good shape. People who don’t know the house are sometimes surprised to find out that it wasn’t built in the last three or four years.

So, was it worth it?

Like all those foolish Grand Designers, we pushed ourselves to the limit financially, and then some. Unquestionably, we would have more money now if we had stayed in our terraced house in Hackney. But it’s never been a financial undertaking, this house: it’s always been about us. One day, it will have a sale price. But, like all handmade things, there is something about its value that you can’t, quite, put a price on.

Comments

Be the first to comment

Do you want to comment on this article? You need to be signed in for this feature